ARTICLE THE DUAL NARRATIVES IN THE LANDSCAPE OF MUSIC COPYRIGHT

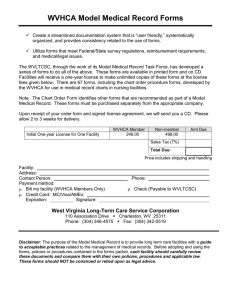

advertisement