Document 10868957

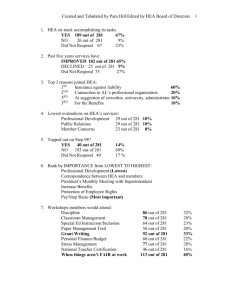

advertisement