Document 10868926

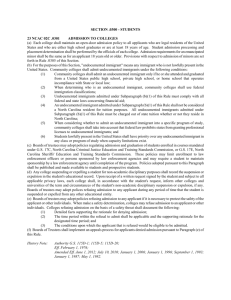

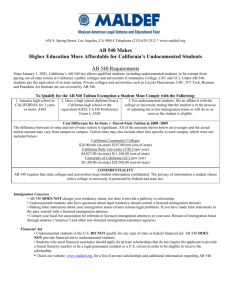

advertisement