Document 10868902

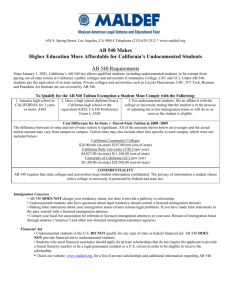

advertisement