Document 10868860

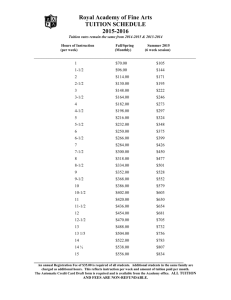

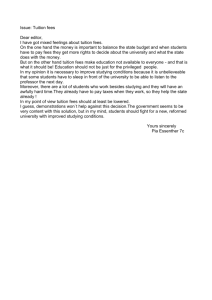

advertisement