Document 10868586

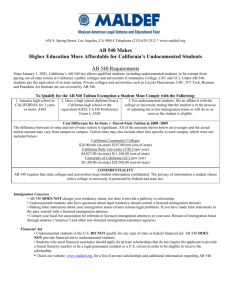

advertisement