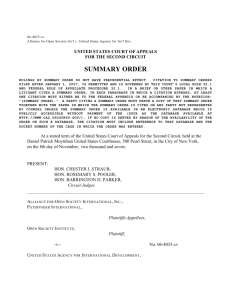

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth...

advertisement