1 THOMAS C. HORNE Firm Bar No. 014000

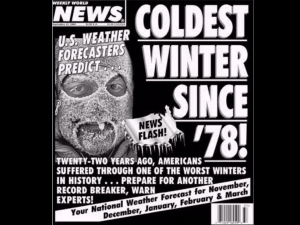

advertisement