Document 10868339

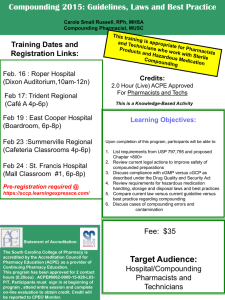

advertisement