Document 10867568

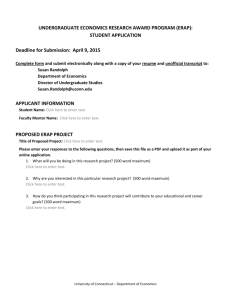

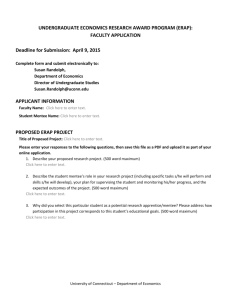

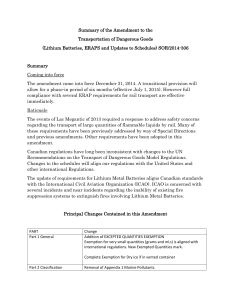

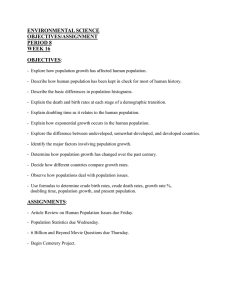

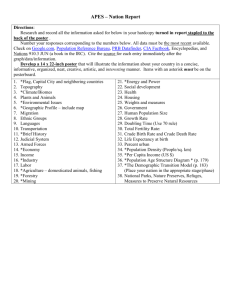

advertisement