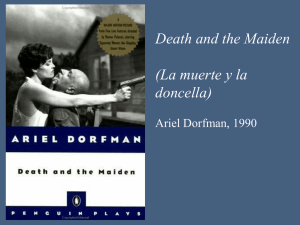

Identity Construction in Intercultural Encounters: A Master Thesis

advertisement