Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, Committee on Energy and Commerce,

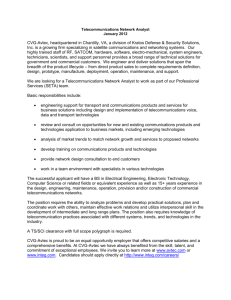

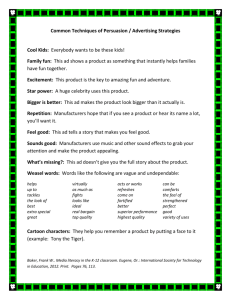

advertisement