Alternative Redevelopment Options for the Kerry Ann McNally

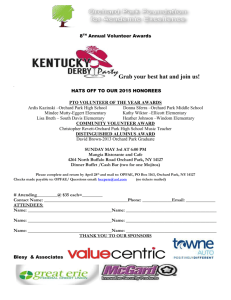

advertisement