Analysis of Enterprise Architecture Alignment:

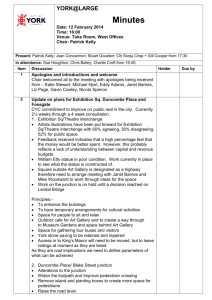

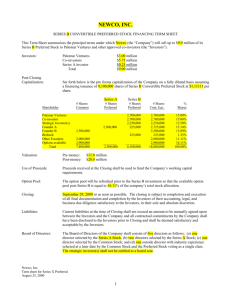

advertisement