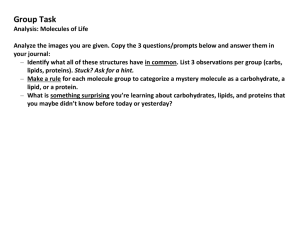

INTACT J. 2006 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements ...

advertisement