by Kevin Lim

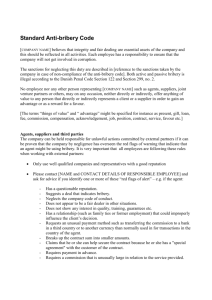

advertisement