JUN IES 9 2010

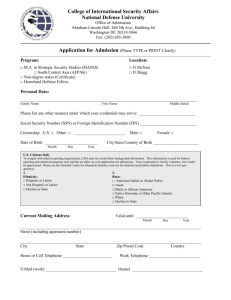

advertisement