Beyond the letter of the law Marcela A. Natalicchio

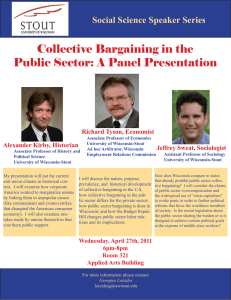

advertisement