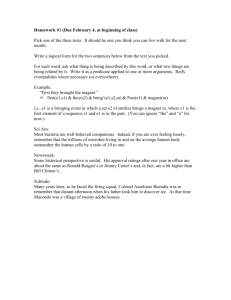

Six Sigma Process Improvements and Sourcing ... Factory Fire

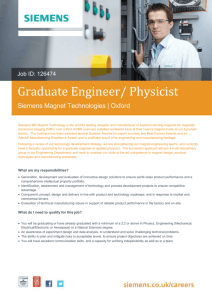

advertisement