Do Migrants Transfer Tacit Knowledge?

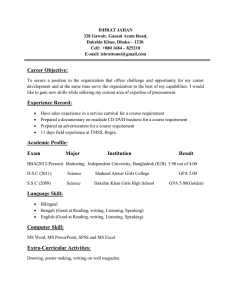

advertisement