BANKING SECTOR STABILITY AND FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION: SOME EVIDENCE FROM MALAYSIA

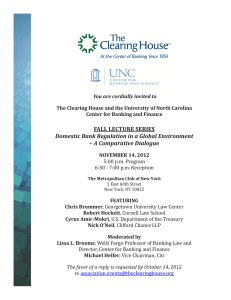

advertisement

BANKING SECTOR STABILITY AND FINANCIAL LIBERALIZATION: SOME EVIDENCE FROM MALAYSIA CHOW FAH YEE* AND EU CHYE TAN ** * Associate Professor, Faculty of Computer and Mathematical Sciences, University Technology MARA, Shah Alam, Malaysia. yeechowfah@yahoo.com.my yeechowfah@salam.uitm.edu.my ** Professor, Faculty of Economics and Administration, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. tanec@um.edu.my ABSTRACT The stability of the banking sector is the focus of every government at this moment. As the global financial crisis that originated from the US subprime mortgage meltdown unfolds, each country scrambled to come up with a plan to shore up calm and confidence. Malaysia has recovered not too long ago from a similar banking debacle, the 1997 East Asian Financial Crisis. The link between financial liberalization and the performance of the Malaysian banking sector is assessed here by employing two techniques. Firstly, using firm level data of Malaysian domestic banks to assess the allocative efficiency of the banking sector. Specifically, it tries to determine whether financial liberalization in Malaysia was able to promote a competitive environment that could boost the efficiency of banks in terms of reduction in intermediation spreads. Using cost-ratio analysis, two series of cost data (pre liberalization and post liberalization) were calculated . Results revealed that all save one of the banks analyzed have not become more efficient after the banking sector is liberalized. Secondly, by mobilizing macroeconomic data and Logistic regression technique to assess the contribution of financial liberalization to the banking crisis of 1997. Results suggest that financial liberalization, banks' lending rates and the ratio of M2 to foreign exchange reserves contribute significantly to the 1997 banking sector crisis. Keywords : Financial Liberalization, Banking crisis, Logistic Regression, Intermediation Spread 1 I. INTRODUCTION The current financial meltdown that swept across the globe jolt to memory the importance of a stable and efficient banking system. The crisis had its roots in the “sub-prime” house mortgage sector in the United States. It then spread to the banks which had invested in financial instruments linked to the value of these sub-prime mortgages. In March 2008, news of a fire-sale of one of the largest and oldest banks in USA , Bears Stearns Inc. stunned Wall Street and pummelled global financial stocks. This was just the beginning of the financial storm. A year later, in USA alone, there are 14 banks that are declared insolvent while the exports of numerous countries worldwide (including Malaysia) have plummeted; thus causing factories to shut down and workers to be laid off. The trail of destruction caused reminisces the 1997 East Asian financial crisis (EAFC). Malaysia was one of the countries that was severely affected then. Besides Malaysia, Thailand, Korea, Indonesia and the Philippines were also badly hit. The toll of the crisis was enormous as it persisted and spread to the real sector. On average, these five economies shrank about 7.7%, with millions of people sustaining livelihood losses (Yellen, 2007). The East Asian financial crisis of 1997 highlighted the link between financial liberalization and instability of the banking sector. All five countries had deregulated their banking systems some time before the onslaught of that banking debacle. Malaysia went through two banking crises. The first crisis was in the mid 1980’s and the second being the 1997 EAFC. The crisis of 1980s was short and less severe compared to the 1997 crisis. During the EAFC, the ringgit (Malaysian currency) depreciated against the US dollar by nearly 50%, while the stock market contracted by more than 60%. The ringgit fell from an average of 2.42 to the US dollar in April 1997 to a low of 4.88 to the US dollar in January 1998 ( Mohamed Ariff, 1999). Real output declined by 6.7% after 12 years of uninterrupted expansion, averaging 7.8% per annum 2 before the onslaught of the EAFC. Per capita income in nominal terms declined by about 30% from US$4284 in 1997 to US$3018 in 1998. This paper aims to contribute to the literature on the link between financial liberalization and the performance of the banking sector by: a) using firm level data of Malaysian domestic banks to assess the allocative efficiency of the banking sector. Specifically, it tries to determine whether financial liberalization in Malaysia was able to promote a competitive environment that could boost the efficiency of banks in terms of reduction in intermediation spreads; and b) mobilizing macroeconomic data to assess the contribution of financial liberalization to the banking crisis of 1997. II. Banking Institutions and Financial Liberalization in Malaysia The banking system in Malaysia consists of the central bank (Bank Negara Malaysia), banking institutions and other financial institutions as shown in Table 1. The banking system is the largest component, accounting for about 70% of the total assets of the Malaysian financial system (Bank Negara Malaysia, 1999). The banking institutions are traditionally the largest mobilizers of deposits. Recent statistics show that they still are: in 2005, for example, the banking institutions mobilized around 83% of the total deposits of the financial system and held about 67% of the financial system’s total assets. The 1997 financial crisis revealed the structural weakness of the Malaysian financial system. Strong loan growth between 1994 – 1997, which averaged about 25% per annum, had led to the high loan exposure of the banking system. In addition the underdeveloped bond market also resulted in the banking system providing a significant portion of the private sector financing, thereby increasing the concentration of risk in the banking sector. The crisis also exposed the vulnerability of the finance companies, whose business was mainly hire purchase financing and consumption credit. Thus the industry became highly vulnerable amidst rising interest rates and a slowdown in the economic activity. As a solution, a merger programme 3 for the finance companies was initiated in January 1998 to consolidate and rationalize the industry. In 1999, the domestic banks were given the flexibility to form their own merger groups and to choose their own leader in each group to lead the merger process. By 2001, the domestic banking sector was subsequently merged into 10 banking groups as shown in Appendix A. Structural reforms after the EAFC have reshaped the financial landscape. Now commercial banking, investment banking and Islamic banking institutions form the nucleus of the financial system. The financial system has become more diversified. The number of players in the financial system have changed significantly after the EAFC. The rationalization programme have led to the formation of financial conglomerates. Today all domestic banking groups undertake full range of commercial banking, investment banking and Islamic banking activities. The latest number of players in the Malaysian financial sector is shown in Appendix B. Malaysia began her path to financial liberalization on October 1978. In line with the doctrine advocated by McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973), interest rates were deregulated to promote a more liberal and competitive financial system. However, on several occasions, the deregulation process had to be put on hold or reversed when the economy faced adverse shocks. Malaysia’s banking sector is considered fully liberalized on February 1991, where each commercial bank can set its own base lending rate according to its own cost of funds. III. Efficiency of Malaysian Domestic Banks A. Financial Intermediation The most basic functions of a financial system are: firstly, to provide an efficient payments mechanism for the whole economy and secondly intermediating between lenders and borrowers. These basic functions are the domain of the banking institutions. Banks together with the other financial intermediaries play a major role in facilitating the overall functioning of an economy. In almost all developing economies like 4 Malaysia, banks are the major suppliers of credit to finance productive investments and other debt-financed activities. The banking system of a country in its sacrosanct role as an intermediary, performs the crucial task of channelling resources from savings to investment. The greater the financialization of savings, the greater the potential for the channelling of savings to productitive activities; and the more efficient the system, the better the mobilization of resources. Table 1: The Malaysian Financial System Financial Institutions Financial Markets Banking System • Bank Negara Malaysia • Banking institutions - Commercial banks (including Islamic Banks) - Finance companies - Merchant banks/Investment banks • Others - Discount houses - Representative office of Foreign banks - Offshore banks in Labuan Non-Bank Financial Intermediaries (NBFI) • Provident and pension funds • Insurance companies ( including Takaful) • Reinsurance cos. • Development finance institutions • Saving institutions - National savings bank - Co-operatives Money & Foreign Exchange Markets • Money market • Foreign exchange market • Capital market • Equity market • Bond market - Public debt securities - Private debt securities Derivative markets • Commodity Futures • KLIBOR Futures Offshore market • Labuan International Offshore Financial Centre Other NBFI - Unit trusts - Universal brokers - Cagamas Bhd. Credit guarantee corp. Leasing companies Factoring Venture capital Source: i): Bank Negara Malaysia, The Central Bank and the Financial System in Malaysia, A Decade of Change, 1999 ii): Bank Negara Malaysia, Financial Stability and Payments Systems Report, 2007 5 With financial liberalization, banks are expected to be more efficient in their operations. With reference to the intermediation function, this means narrowing the margin between what they pay for financial resources (the deposit rate) and what they earn on them (the loan rate). The difference between the deposit rate and the loan rate is referred to as the interest spread (or interest margin). For the Malaysian banks, margin is the main source of their profits (Cheah, 1994). In a fully liberalized environment, competition should reduce spreads and enhance bank performance and efficiency. According to Lin (1990), the ability of the banks to reduce their lending margins without crippling the system’s financial health is an indicator of the efficiency of the banking system. Hence interest margin can be regarded as an indicator of the banks’ efficiency in financial intermediation. B. Cost Ratio Methodology Revell (1980) conducted a comprehensive survey on the cost of intermediation and interest-rate margin. The main objective was to investigate an assumed increase in the cost of intermediation in the OECD countries. Gross earning margins (GEM) was the variable used to indicate cost of intermediation as it represents what the customers of the banking institutions have to pay for the services offered. In this paper, the cost-ratio analysis procedure established by Revell is adopted to evaluate the efficiency of the banking system in terms of intermediation costs. By comparing two series (pre-liberalization and post-liberalization) of cost ratio data, we would be able to ascertain whether the banking system’s cost of intermediation has increased or decreased over time. This in turn allows us to infer about banks’ efficiency following financial liberalization. The ratio of GEM over bank’s total assets is used as a proxy for the bank’s efficiency. GEM would appear in the numerator, while the total assets of the banking institutions would be the denominator. The items that are extracted from the income statements of banks to calculate the gross earning margin figures are: 1. Interest received Interest paid 2. 3. Other income (net). Items 1 and 2 include only interest received and paid on loans and deposits. Interest and income from other 6 sources such as investment in securities, foreign exchange operation and other fees and commission are found in item 3. Interest margin is the difference between item 1 and 2. While the total sum of interest margin and item 3 gives the broadly defined margin ( gross earning margin) received by banks in their financial operations. This sum is also commonly referred to as the “banker’s spread”. In other words, GEM can be define as follows: GEM = (Interest received – Interest paid) + Other Income = Interest margin + Other income C. Data for Cost Ratio Analysis Related data of selected banks in Malaysia are compiled from 1987 to 1997. These years are chosen based on data constraints. 1987 is the earliest year that has data in the form of aggregation described above, or in a form, from which the required data can be extracted from the published sources. While, 1997 is the last year in the series due to the banking merger exercise that followed after the financial crisis of 1997. The crisis had affected a number of banks adversely. There is also the issue of the bank entity itself. Banks that are chosen are those that have been established long enough (at least from 1987 to 1997) and have not encountered significant changes in management or mergers during the period under study. A number of banks in the Malaysian banking system have gone through mergers during the 1990’s. Mergers give rise to considerable consolidation in banks’ accounts making it very difficult to compare the banks’ accounts from one period to another, especially if previous period is before the merger. Owing to the above constraints, only seven of the Malaysian domestic banks are selected for a cost ratio analysis. The main sources of statistical information are the Balance Sheets and Profit and Loss Accounts of the banking institutions. The cost ratio series from these banks provide an indication of the banking institutions’ efficiency over the years, especially before and after financial liberalization. 7 D. Results of Cost Ratio Analysis The mean (or average) intermediation spread is calculated for both the pre liberalization years (1987 – 1991) and for the post liberalization years (1992 – 1997). The mean GEM/Total Assets ratios are given in Table 2 below, while some descriptive statistics for these ratios are given in Appendix C. From these mean values (as seen in Table 2), it would seem that most of the banks (five out of seven) showed an increase in the spread in the post liberalization period. Only banks F and D had a reduced GEM/Total Assets ratio in the post liberalization period. In order to investigate if there were indeed significant changes in the mean ratios between the pre and post-liberalization periods, statistical analysis using the non parametric method is employed here. Non parametric test is used when the distribution of the data is not normal. From Table 3, the test reveals no significant difference in the GEM ratio between pre and post liberalization periods for all banks except for Bank D. This implies that the intermediation spread of all the banks sampled did not change materially with financial liberalization except for one, i.e. Bank D. Hence, the results generally indicate that a more liberalized environment in Malaysia did not seem to have enhanced bank efficiency in terms of reducing the bankers’ spread. Out of seven, only one bank had a lower average intermediation spread in the post- liberalization period. Table 2: Mean GEM/Total Assets Ratio for Both Periods Bank Pre ( x pre ) Post ( x post ) Diff erence ( x pre − x post ) Change A B C D E F G 5.2742 4.6962 3.4383 2.9766 3.5260 3.0860 3.6083 -0.6087 -0.4142 -0.3423 0.4609 -0.1319 0.2194 -0.4200 Increase Increase Increase Decrease Increase Decrease Increase 4.6654 4.2819 3.0960 3.4375 3.3941 3.3054 3.1883 8 Table 3: Mann-Whitney U Test Results Bank Pre ( x pre ) Post ( x post ) Diff erence ( x pre − x post ) p-values Results A B C D E F G 5.2742 4.6962 3.4383 2.9766 3.5260 3.0860 3.6083 -0.6087 -0.4142 -0.3423 0.4609 -0.1319 0.2194 -0.4200 0.361 0.144 0.068 0.028* 0.361 0.361 0.068 Not significant Not significant Not significant Significant Not significant Not significant Not significant 4.6654 4.2819 3.0960 3.4375 3.3941 3.3054 3.1883 * p-value < 0.05 IV. Financial Liberalization and Banking Sector Stability A. Financial Liberalization Proponents of financial liberalization believe that deregulation would bring about a host of benefits which would boost economic growth; among them, improving the efficiency and performance of the financial system, product innovation and lower prices. However, in the last three decades, we have witnessed the pitfalls that a liberalized regime could bring. Amongst them, increased use of credit to purchase assets and finance consumption, asset price inflation and volatility and financial fragility. Alba (1999), Akyuz (1993) and a World Bank study (1990) noted that with financial liberalization came a generalized surge in bank lending and a greater bank exposure to the real estate sector. While Agrawal (1992) pointed out that financial liberalization often leads to the prices of shares , real estate first rising sharply, inducing many people to invest or speculate in these markets with some funds borrowed from banks at very high real interest rates. The prices later decline, causing many people who had earlier borrowed at high real interest rates to become insolvent and this leaves the banks with a large portfolio of non-performing loans which eventually causes their insolvency. 9 B. The 1997 Financial Crisis Various views had been put forward to explain the cause of the crisis. Among them , poor macroeconomic management. However, as noted by Akyuz (2004) and Jomo (2001), the majority of the East Asian countries that were affected ( including Malaysia), have track records of sustainable development and macroeconomic discipline. Akyuz stressed that the great susceptibility of domestic financial condition in developing countries to currency instability is due primarily to the existence of large stocks of public and private debt denominated in foreign currencies. In his opinion, this is the main reason why currency crises in emerging markets spill over to domestic financial markets, not bad macroeconomic policies. Then, they are those that attributed the crisis to crony capitalism. The more plausible explanation would be the inefficient process of financial liberalization. After Malaysia had fully liberalized her financial sector on Feb 1991, there was a tremendous loan growth in the banking sector. For the 1992-1994 period, total annual loan growth averaged 12.2%. In 1995, the growth rate surged to 26.8%. Together with liberalization of international capital flows, the supply of money and credit in the economy was boosted to unhealthy levels. According to the 1997 Bank Negara report, large amount of foreign funds entered in 1992 and 1993 mostly in the Kuala Lumpur stock exchange, pushing capitalization to 375% of GDP at the end of 1993. With liquidity abound and a bullish stock market, Malaysian consumers amassed huge amounts of debts (loans for purchase of stocks and shares, and installment credit for cars and properties). With the onslaught of the contagion in mid 1997, there was a large and rapid withdrawal of funds by the foreign portfolio investors, thus contributing to the dramatic fall of the Kuala Lumpur stock exchange index ( by 50%). The property bubble subsequently burst. As a result, non-performing loans in the banking system rose. Before long, the impact of the crisis was transmitted quickly to the real sector . 10 C. Empirical Studies on Banking Crises Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache (1998), Kamisky and Reinhart (1999) and also Cole and Slade (1998) stressed that financial liberalization is a contributing factor to the banking crises that had occurred. Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache explored empirically the relationship between banking crises and financial liberalization in 53 countries, including Malaysia (for 1980 – 1995), using a multivariate logit framework. They found that banking crises are more likely to occur in liberalized financial systems. The results derived showed a number of factors including adverse macroeconomic developments, bad economic policies as being the other potential explanatory variables. While Kaminsky and Reinhart reported that in 18 out of the 25 banking crises surveyed by them, the financial sector had been liberalized. Zhuang (2002) also tested empirically the link between financial liberalization and bank instability. The factors considered in these studies included both bank specific and macroeconomic variables. The ratio of M2 to foreign exchange reserves, total bank loans divided by the country’s GDP and the current account balance have been found to affect bank stability. V. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis A. The Model The logistic regression model can be expressed as follows: P(Yi = 1) = 1 1 + e −Z , i = 1,…, N ------------ (1) Where Z = b0 + b1X1 + b2X2 + … + bMXM P = the probability that the observed value Y takes the value 1 N = the number of observations X = the explanatory variables M = the number of explanatory variables Y = the dependent variable ;Y =1 for bank crisis period and Y= 0 for non crisis period. 11 Equation (1) above is a cumulative logistic distribution function with P representing the probability of a bank crisis which can be estimated. Logistic regression is appropriate when the dependent variable is grouped into discrete states. The explanatory variables include the financial liberalization variable and other control variables. Like most studies on financial liberaliztion, the removal of interest rate controls is considered the centerpiece of financial liberalization. For Malaysia, it is only on February 1, 1991 that the BLR (base lending rate) was freed from the administrative control of the central bank. B. Variables In The Model In this study the control variables that capture the characteristics of the banking system namely, ratio of M2 (currency in circulation plus demand and time deposits) to foreign exchange reserves (an indicator of vulnerability to sudden capital outflows) and lending rate are included. The ratio of M2 to foreign exchange reserves is a measure of the country’s ability to withstand the pressure of substituting foreign currency for domestic currency by investors. A rise in the M2/ foreign exchange reserves ratio implies a decline in the foreign currency backing of the short-term domestic currency liabilities of the banking system. Hence this would make the banking system vulnerable to sudden capital outflow. Malaysia opened its capital account as part of its ongoing financial liberalization program. With this development, there was a massive inflow of foreign capital, in particular portfolio investment. When the crisis precipitated in July 1997, these funds took flight easily. As noted by ChanLau (1998), the private capital flows to the five economies most affected by the EAFC, reversed from a net inflow of US$93 billion in 1996 to a net outflow of US$12 billion in 1997. Lending rate is included in the model as after financial liberalization, with the elimination of interest rates controls, banks are free to set the rates charged on borrowing. Hence, banks could be motivated to profit from the new found freedom of setting interest rates, as long as interest gains are larger than the loss from the increased risk. In essence, this means that 12 unregulated financial markets can lead to higher interest rates and greater risk- taking (Akyuz, 1993). Apart from these variables, the rate of real GDP growth (Rgdpgrow) is also included, given that adverse shifts in the macroeconomic condition of a country could weaken its financial sector. Hence, for this study the Z variable in equation (1) is as follows: Z = b0 + b1fin.lib + b2lend + b3M2tofor + b4Rgdpgrow Where : Z = the logged odds of the banking crisis finlib = liberalized or non-liberalized period lend = banks’ lending rates M2tofor = ratio of M2 to foreign exchange reserves Rgdpgrow = rate of real GDP growth C. Data for Logistic Regression Logistic regression literature suggests that the sample should contain a reasonable representation of both the alternative outcomes for the dependent variable (which in this case is a banking crisis period or non banking crisis period). In order to get a reasonable number of the banking crisis period, quarterly data is used. Furthermore, 1990 is the earliest year in which quarterly data for GDP is available. Hence, quarterly data for the period of 1990 until 2005 is used in this study. All the data needed are sourced from the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics and Bank Negara Malaysia’s Quarterly Economic and Monthly Statistical Bulletins. D. Logistic Regression Results Based on the model building strategies given by Hosmer and Lemeshow (2000) and model evaluation criteria by Menard (2001), the following model as shown in Table 4 is considered the most appropriate to address the banking crisis hypothesis of this study. Three of the predictor variables; 13 financial liberalization (Fin Lib) , ratio of M2 to foreign exchange reserves (M2tofor) and bank lending rates (Lend) are statistically significant. The following two tables furnish the results of the model used while the rest are shown in Appendix D. The odds ratio for the financial liberalization variable is 16.31. This implies that when all the other variables are held constant, with financial liberalization the banking sector is 16 times more likely to encounter a banking crisis. Table 4: Estimation Results Predictors Fin. lib. Lend M2tofor Constant B 2.79 1.19 0.90 -21.13 S.E 1.37 0.54 0.33 6.76 Wald 4.18 4.85 7.46 9.78 df 1 1 1 1 Sig. 0.041** 0.028** 0.006** 0.002** Exp (B) 16.31 3.30 2.45 0.000 Notes: i) ii) iii) iv) v) vi) vii) B = the logistic regression coefficient S.E. = standard error of the coefficient Wald = Wald statistic to test the significance of the individual coefficient df = degree of freedom Sig. = the p-value for the Wald statistic Exp(B) = the odds ratio of the predictor variable ** Indicates significance level at 0.05 and less Table 5 : Classification Table for Prediction of Banking Crisis Observed 0 Crisis 0 1 53 2 Overall percentage Predicted Percentage Crisis Correct 1 0 7 100.0 77.8 96.8 The other two variables, namely ratio of M2 to foreign exchange reserves (m2tofor) and lending rates of the commercial banks (lend) could also raise albeit to a smaller extent the odds of a banking crisis happening, as they 14 grow. The classification table below suggest that this model predicted the outcome (banking crisis) very well. The percentage of the non-occurrence of the crisis correctly predicted is 100 per cent; while the percentage of occurrence of the crisis correctly predicted is 77.85 per cent, giving an overall success rate of 96.8 per cent. VI. Conclusion The impact of financial liberalization on the performance and stability of Malaysian banks has been assessed based on cost-ratio-analysis and logistic regression analysis. The cost ratio analysis has revealed that all save one of the banks analyzed, have not become more efficient (in terms of having a lower intermediation spread) after the banking sector is fully liberalized. This indicates that a liberalized environment was not sufficient to promote efficiency among the banks, conversely, the banks seem to be able to keep a larger interest spread and hence, higher profits The logistic regression analysis showed that financial liberalization could independently exert a negative effect on the stability of the banking sector when other factors are controlled. Besides financial liberalization, the factors that could contribute significantly to a banking sector crisis were the M2 to foreign exchange reserves ratio and the banks’ lending rates. Results of the logistic regression also suggest that capital account liberalization attracted mobile capital that caused damaging effects to the Malaysian economy for the period studied. One of the views put forward to explain the EAFC was poor macroeconomic management. Hence this study provides empirical evidence that apart from financial liberalization, the banking crisis also has a lot to do with the banking sector’s performance and not much with the country’s macroeconomic condition. This is plausibly due to the adoption of financial liberalization before putting in place an effective prudential regulatory system. In a liberalized environment, banks may be tempted to take excessive risks in their lending activities; overlending to the broad property 15 sector and for speculative purposes rather than for sound investment purposes, in the absence of adequate monitoring. This study reinforces the recommendation made by central bankers after the EAFC; that the process of financial deregulation should be accompanied by stronger prudential supervision and regulation. Supervision of banking institutions is just as important if not more for non- financial public listed firms. Regulatory agencies should ensure that financial institutions are properly managed, transparent in their operations and have strong risk management. Indeed, a deregulated banking system ought to have more not less supervision. This could not resonate more truth than now, as half the world is in recession, in large part due to unfettered financial liberalization. 16 References Alba, P. et. al. (1999), ‘Volatility and Contagion in a Financailly Integrated World’,in Asia Pacific Financial Dergulation, (eds), Brouwer, routledge, London. Agrawal, P. (1992), ‘Financial Liberalization and Financial Crisis in Developing Countries’ in National Conference on Economic Globalization; Issues, Challenges and Responses by Developing Countries. Langkawi, Malaysia. Akyuz, Y. ( 2004), Managing Financial Instability and Shocks in a Globalizing World, Public Lecture, Tun Ismail Ali Chair, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Akyuz, Y. (1993), Financial Liberalization: the Key Issues, UNCTAD, no.56. Bank Negara Malaysia. (1999). The Central Bank and the Financial System in Malaysia, A Decade of Change. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Bank Negara Malaysia. (2007). Financial Stability and Payments System Report. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Chan-Lau, J. and Chen Z.H. (1998)., ‘Financial Crisis and Credit Crunch as a Result of Inefficient Financial Intermediation-With Reference to the Asian Financial Crisis’, IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund. Cheah, K.G. (1994)., Financial Institutions in Malaysia. Institute of Bankers Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Cole, D.C. and Slade, B.F.( 1998)., ‘The Crisis and Financial Sector Reforms’, Asean Economic Bulletin , 15, 338-346. Demergic-Kunt, A.,Detragiache, E. (1998)., Financial Liberalization and Financial Fragility. IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund . Hosmer, D.W. and Lemeshow S. (2000)., Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley and Sons Inc. Jomo, K.S. (ed) (2001), Malaysian Eclipse: Economic Crisis and Recovery. Zed Books, London Kaminsky, G.L. and Reinhart, C.M. (1999). “ The Twin Crises: The Causes of Banking and Balance-of-Payments Problems”, American Economic Review, 89, 473-500. Lin S. Y. (1990)., ‘Productivity in the Banking System’, Journal of Economic Studies. XXVII, No.1 , 65-87. 17 Malaysian McKinnon, R. (1973)., Money and Capital in Economic Development . The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C. Menard, S. (2001). Applied Logistic Regression Analysis. Sage Publications. Mohamed, Ariff .(1999). “The Malaysian Financial Crisis: Economic Impact and Recovery Prospects”, The Developing Economies, XXXVII 4 , 417-438. Revell, JRS. (1980). Costs and Margins in Banking: An International Survey. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Shaw. E. (1973)., Financial Deepening in Economic Development. New York: Oxford University Press. World Bank. (1990). Financial Systems and Development, Policy and Research Series, The World Bank. Yee C. F. Yap B.W. and Mazni M. (2004). Financial Liberalization and Allocative Efficiency of The Banking System. IRDC Paper, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia. Yellen, J.L.( 2007). The Asian Financial Crisis Ten Years Later: Assessing the Past and Looking to the Future, Article downloaded from the net; http://www.frbsf.org/news/speeches/2007/0206.html Zhuang, J. (2002). Asian Financial Crisis: What Can an Early Warning System Model Tell Us? ERD Working Paper No. 26, Asian Development Bank 18 Appendix A: Merger Programme for Malaysian Domestic Banks Original Anchor Banking Group 1. Affin Bank Berhad Group Perwira Affin Bank Bhd Asia Commercial Finance Bhd Perwira Affin Merchant Bank Bhd. 2. Alliance Bank Berhad Group Multi-Purpose Bank Berhad 3. Arab-Malaysian Bank Bhd. Group Arab-Malaysian Bank Berhad Arab-Malaysian Finance Bhd Arab-Malaysian Merchant Bhd 4. Bumiputra Commerce Bank Berhad Group Bumiputra Commerce Bank Berhad Bumiputra Commerce Finance Berhad Commerce International Merchant Bankers Berhad 5. EON Bank Berhad Group EON Bank Berhad EON Finance Berhad 6. Hong Leong Bank Berhad Group Hong Leong Bank Berhad Hong Leong Finance Berhad 7. Malayan Banking Berhad Group Malayan Banking Berhad Mayban Finance Berhad Aseambankers Malaysia Bhd 8. Public Bank Berhad Group Public Bank Berhad Public Finance Berhad 9. RHB Bank Berhad Group RHB Bank Berhad RHB Sakura Merchant Bankers Bhd 10.Southern Bank Berhad Group Southern Bank Berhad Merged with Resultant Merger Entity after BSN Commercial Bank (M) Bhd BSN Finance Bhd BSN Merchant Bankers Berhad Affin Bank Berhad Affin ACF Finance Berhad Affin Merchant Bank Berhad International Bank Malaysia Bhd Sabah Bank Berhad Sabah Finance Berhad Bolton Finance Berhad Amanah Merchant Bank Berhad Bumiputra Merchant Bankers Bhd Alliance Bank Berhad Alliance Finance Berhad Alliance Merchant Bank Berhad MBf Finance Berhad Arab-Malaysian Bank Berhad Arab-Malaysian Finance Berhad Arab-Malaysian Merchant Bank Berhad Bumiputra Commerce Bank Berhad Bumiputra Commerce Finance Berhad Commerce International Merchant Bankers Berhad Oriental Bank Berhad City Finance Berhad Perkasa Finance Berhad Malaysian International Merchant Bankers Berhad EON Bank Berhad EON Finance Berhad Malaysian International Merchant Bankers Berhad Wah Tat Bank Berhad Credit Corporation Berhad Hong Leong Bank Berhad Hong Leong Finance Berhad (Malaysia) The Pacific Bank Berhad PhileoAllied Bank (M) Berhad Sime Finance Berhad Kewangan Bersatu Berhad Malayan Banking Berhad Mayban Finance Berhad Aseambankers Malaysia Berhad Hock Hua Bank Berhad Advance Finance Berhad Sime Merchant Bankers Berhad Public Bank Berhad Public Finance Berhad Public Merchant Bank Bhd Delta Finance Berhad Interfinance Berhad RHB Bank Berhad RHB Delta Finance Berhad RHB Sakura Merchant Bankers Berhad Bah Hin Lee Bank Berhad United Merchant Finance Berhad Perdana Finance Berhad Cempaka Finance Berhad Perdana Merchant Bankers Bhd Source: Bank Negara Malaysia 2001 19 Southern Bank Berhad Southern Finance Berhad Southern Investment Bank Berhad Appendix B: Malaysian Financial Sector: Number of Players Financial Institutions Commercial Banks Finance Companies Investment Banks/Merchant Banks Universal Brokers Discount Houses Islamic Banks Insurance Companies Reinsurance Companies Takaful Operators Retakaful Operators Development Financial institutions 1 1999 34 32 12 5 7 2 56 11 2 0 14 2007 22 01 14 1 0 11 41 7 8 2 13 Rationalization of finance companies and commercial banks within a banking group. Source: Bank Negara Malaysia, Financial Stability and Payments Systems Report 2007. 20 Appendix C: Descriptive Statistics for GEM Ratios GEM ratios in the pre-liberalization period (1987 – 1991) Bank Minimum Maximum Mean Median A B C D E F G 5.4950 4.7921 3.3688 3.9005 4.1935 3.7205 3.5003 4.7476 4.2508 3.0572 3.5260 3.2432 3.2419 3.2780 3.8359 3.7920 2.8192 2.9303 2.9230 2.9157 2.7646 4.6654 4.2819 3.0960 3.4375 3.3941 3.3054 3.1883 Std. Dev 0.6172 0.3612 0.2604 0.3592 0.5201 0.3246 0.2807 N 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 GEM ratios in the post-liberalization period (1992 – 1997) Bank Minimum Maximum Mean Median A B C D E F G 6.7638 5.2605 3.8811 3.2597 3.7666 3.5637 4.2003 4.9977 4.6038 3.4572 2.9857 3.5227 3.0705 3.5027 4.2320 4.1848 2.9943 2.6607 3.2290 2.6649 3.2769 5.2742 4.6962 3.4383 2.9766 3.5260 3.0860 3.6083 21 Std. Dev 0.9128 0.3887 0.3041 0.2886 0.2231 0.4322 0.3289 N 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 Appendix D : Logistic Regression Output Using SPSS Block 1: Method = Forward Stepwise (Likelihood Ratio) Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients Chi -square 16.094 df 1 Significance 0.000 Block 16.094 1 0.000 Model Step 2 Step 16.094 8.571 1 1 0.000 0.003 Block 24.665 2 0.000 Model Step 3 Step 24.665 4.347 2 1 0.000 0.037 Block 29.012 3 0.000 Model 29.012 3 0.000 Step 1 Step Model Summary Step -2 Log likelihood Cox & Snell R Square Nagelkerke R Square 1 35.270 .229 .406 2 26.669 .328 .583 3 22.352 .374 .663 Classification Table Observed Predicted Crisis Step 1 0 1 0 51 2 96.2 1 5 4 44.4 53 0 88.7 100.0 1 4 5 55.6 Overall Percentage crisis 0 53 0 93.5 100.0 1 2 7 77.8 crisis Overall Percentage Step 2 crisis 0 Step 3 Percentage correct Overall Percentage 96.8 22 Variables in the Equation Step m2tofor B 0.75 S.E. 0.24 Wald 10.17 df 1 Sig. 0.001 Exp(B) 2.113 1 constant -9.61 2.69 12.76 1 0.000 0.000 Step lend 1.05 0.48 4.76 1 0.029 2.85 2 m2tofor 0.79 0.30 7.03 1 0.008 2.19 constant -18.23 6.05 9.07 1 0.003 0.000 Step fin. lib 2.79 1.37 4.18 1 0.041 16.31 3 lend 1.19 0.54 4.85 1 0.028 3.30 m2tofor 0.90 0.33 7.46 1 0.006 2.45 constant -21.13 6.76 9.78 1 0.002 0.000 Variables not in the equation Step 1 variables fin.lib score 5.537 df 1 sig 0.019 lend 7.097 1 0.008 rgdpgrow 0.251 1 0.617 12.420 5.829 3 1 0.006 0.016 0.442 1 0.506 6.895 2 0.032 1.182 1 0.277 1.182 1 0.277 Overall statistics Step 2 variables fin.lib rgdpgrow Overall statistics Step 3 variables rgdpgrow Overall statistics 23