Draft, subject to changes. P.L. Arya

advertisement

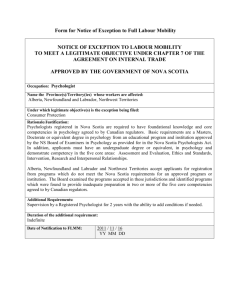

Draft, subject to changes. COLLUSIVE OLIGOPOLY AND GASOLINE PRICE REGULATION IN NOVA SCOTIA P.L. Arya Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada In response to complaints of consumers and some gas station owners, the government of Nova Scotia regulated the fuel prices from 1st July 2006. The present paper examines the effectiveness of gasoline price regulation when suppliers of gasoline are acting as collusive oligopoly. The effectiveness is studied with respect to effects on consumers and gasoline retailers. There are two studies which evaluate the petroleum product pricing in Nova Scotia. The one is a two year review prepared by Gardner Pinfold Consulting Economists prepared for the Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations. This study points out that most objectives of gasoline price regulations are met. The other study is by Bobby O’Keefe of Atlantic Institute for Market Studies (AIMS). This study points out that Nova Scotians are paying more for gasoline under regulation than they would have paid if there was no regulation. Although there is some merit in both the studies, the present paper points out that the collusive oligopoly market structure has important implications for the price of gasoline and may well explain the ineffectiveness of regulation. Introduction: The rise of gasoline price as a result of hurricane Katrina in August 2005, which disrupted the oil supply, led consumers in Nova Scotia to demand price regulation. The variations in price from morning to afternoon on one day frustrated drivers. At the same time, gas retailers, particularly in the rural areas, were finding it hard to keep afloat. The decline in demand coupled with decline in retail margin had a negative impact on their business. The pressure on the government of Nova Scotia to regulate gasoline prices was building since 2004. The government hired consultants and formed committees to study the impact of regulation. The gas price regulation became a reality from 1st July 2006. According to the government of Nova Scotia, regulation is aimed at solving the following problems: (1) Increase in price volatility, (2) declining dealer margins and rural infrastructure and, (3) wide variations within the province. From the consumer perspective, the one objective missing was high price of gasoline. According to the government of Nova Scotia, the wholesalers would be assessed a fee of 0.0009 per litre sold to cover regulatory costs. The Department of Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations (hereafter called the regulator) is the interim regulating authority of gasoline prices. Pricing Formula The regulator takes the average of New York harbor’s daily spot price of gasoline for one week (initially for two weeks) as the benchmark price. The spot price is taken from Platt’s daily spot price data. The U.S. dollar value is converted to Canadian dollar and a wholesale margin of 6 cents per litre is added to the benchmark price before adding federal tax and provincial tax to obtain “fixed” wholesale price. Transport cost of carrying gasoline from refinery to a particular zone is added. For Halifax it is 0.3 cents and for other zones it is higher. Then retail margin of minimum 4 cents per litre is added to get the minimum regular gasoline price at the pump. For mid-grade gasoline additional 3 cents per litre and for premium grade gasoline additional 6 cents per litre is allowed at the wholesale level. For self serving pumps the maximum price of regular gasoline is fixed too. It is 1.5 cents above the minimum retail price. For full service gasoline pumps there is no maximum limit. As an example, the price fixed for gasoline by the regulator on 17th September 2008 was as follows: Benchmark price for regular gasoline Add wholesaler’s margin Add federal tax Add Provincial tax Equals Fixed Whole sale Price Add min. retail markup for self serve Add max. retail markup of self serve Add 0.3 cents for transport cost to Halifax Add 13% of provincial HST Min. price of regular self serve gasoline Max. price of regular self serve gasoline Min. price of regular full serve Max. price of regular full serve 83 cents 06 cents 10 cents 15.5 cents = 114.5 cents 4 cents 5.5 cents =118.8 min. and 120.3 cents max. 15.44 cents min and 15.64 cents max. = 134.2 cents = 135.9 cents = 134.2 cents = 999.99 cents In rural areas most gas stations are full serve and sale volume is low. Initially a cap was placed on the maximum price which full serve gas stations could charge. After a protest by the rural gas station owners, this cap was removed. At present, full service gas stations are not subject to maximum price ceiling. Although price for self serve gasoline is allowed to vary by 1.5 cents per litre, all gas stations in the neighborhood charge the minimum price set by the regulator. In rural areas the gas stations are far from each other and charge higher price. The benchmark price includes adjustment for forward averaging. If the wholesaler has bought the supply and next day price fell, his margin might have reduced if he sold at the fixed regulated price. The regulator makes an adjustment in the benchmark price so that the wholesale margin is not reduced. Similarly, if prices are rising and the wholesaler has bought at a lower price a day before, a downward adjustment in the regulated price is made so that the wholesaler gets the determined margin and not more. The forward averaging is used to give wholesaler a fixed regulated margin. Interrupter and Catastrophic clauses: Market forces determine the spot price. If the average spot price changes 4 cents per litre, the regulator changes the regulation price even if is not Friday, the regular day of change. If there is a sudden large change in the market price due to some catastrophic event, the regulator changes the regulated price immediately. The regulated price reflects sudden market fluctuations. Opting out clause: The parties involved in gasoline distribution may opt out of regulated margins if they decide to do so. For instance, a fully integrated company, Imperial Oil (Esso), which has its own refinery and run many of its own gas stations, has opted out of the regulated margins. Similarly, the Imperial Oil has leased out its gas stations to other retailers and has contracts with them. These independent retailers have opted out of the regulated margins because accepting them would mean violation of their contractual obligations. In the case of companies which have opted out, the regulator sets only the final selling price of the gasoline and leaves the margins as per existing arrangements. Effects of Regulations Gardner Pinfold’s Two Year Review The Effects of regulation are studied in relation to the stated objectives. The detailed study of the effects of regulation is done by Garner Pinfold Consulting Economists for Service Nova Scotia (the regulator) in their two year review. The first objective of regulation was to stabilize price. (i)All parties know that the price would be fixed on Fridays and that it would last for one week unless unforeseen event prompts the regulator to use catastrophic or interrupter clauses. (ii) The regulated price changes are less than the price changes in the unregulated markets in North America. (iii) Regulation has removed the price differences in various regions of Nova Scotia. The regulated price differences reflect transport cost differences. (iv) Even though price variation is allowed between minimum and maximum regulated price of self serve gasoline, competition among gas stations drive the price to the lower limit. The second stated objective was to halt the decline of service stations, particularly in the rural areas by regulating their margins. (i) According to the “Two Year Review”, about 50% of the rural retail gasoline dealers indicated that they are better off with regulated margins, 25% stated that they are worse off and another 25% stated that they are just the same. (ii) The decline in rural gas stations has slowed down. (iii) Higher labour costs and credit card costs are eroding margins. The regulation formula does not take these costs into consideration. (iv) Some company owned gas stations give coupons or price discounts or have other loyalty schemes. These schemes have adverse effects on the sales and hence viability of independent dealers. (v) About 60% of the independent dealers opted out of regulated margins. This is on the top of company owned stations, all of which have opted out of regulation. This according to Pinfold “does not represent a reliable indicator of the merits of regulatory program from a dealer’s perspective.” The third stated objective of regulation is to minimize cost to consumers. According to Pinfold, “Regulation in Nova Scotia has fixed margins, serving to constraint the ability to pass on the rising costs industry faces.” At the same time Pinfold states, “The average marketing margin across Nova Scotia has risen by estimated 0.51 cpl in two years since the regulation was introduced.” Pinfold asserts: “Regulation in Nova Scotia was not intended to reduce prices, but to stabilize them without adding significantly to the price level.” (Pinfold, 2008, p.47). Pinfold’s all estimations are before tax. When we talk of the retail price, we generally talk of price paid by consumer at the pump which includes all taxes. For this reason, the fuel focus reports of Natural Resources Canada are more relevant. As a result of regulation there are no price fluctuations within a week except when catastrophic or interrupter clauses are used. But over a week as a whole, consumers pay more than the free market price. The additional price may be considered as insurance premium paid by consumers to avoid intraweek fluctuations in prices. As for as objective of controlling the decline of service stations in the rural areas is concerned, we are not sure if the decline has reduced because of regulation or after a large decline, it trickled down own its own. No mention is made in the Pinfold’s study of a direct question to the retailers suggesting if they would have exited the market had there been no regulation. The third objective of minimizing cost to consumer is simply not true. As Pinfold’s review itself suggests that consumers pay more for gasoline after regulation. Atlantic Institute for Market Studies’ Review The AIMS study was done by Bobby O’Keefe. The focus of this study is on marketing margins before and after gas price regulation. He takes Pinfold’s figure of 0.51 cents per litre and converts into how much extra money buyers of gasoline have paid in Nova Scotia after regulation. Estimated gasoline sales volumes and extra consumer costs Under regulation in Nova Scotia ________________________________________ Extra cost before tax (cents/L) 0.51 Extra cost including tax (cents/L) 0.58 Total consumption under regulation to February 1, 2009 (millions of L) 2985.2 Total extra cost of regulation from 1 July 2006 to 1 February 2009 $17,868,951 Total extra cost per year $6,745,313 _________________________________________ This table is taken from Bobby O’Keefe, “What’s Missing From Your Wallet”, AIMS Background Paper, February 2009. Since O’Keefe’s study builds on Pinfold’s assertion of cost of regulation, it does not add any thing new to enhance the knowledge. However, it gives consumer the idea of total cost of regulation as against per litre cost. Can the government of Nova Scotia regulate the price of gasoline which reflects the cost of production rather than controlling only the dealer’s and retailer’s margins? The answer is no. The price of gasoline depends on its demand and supply, the latter depends on several factors including the structure of the market. Market Structure of Gasoline Industry in Nova Scotia The gasoline market is concentrated. There are a few large gasoline suppliers. The major suppliers of Nova Scotia gasoline market are: Irwin, Imperial (Esso, owned by Exxon Mobil), Petro-Canada, Shell and Ultramar. The additional player in the gasoline market is Wilson Fuels, which is the wholesale supplier for Esso and owns Esso brand and its own brand retail outlets. These companies together supply to more than 90% of the Nova Scotia market. The four firm concentration ratio (CR4) is over 70 percent. The Hirschman-Herfindahl index (H-index) is about 2000. Both CR4 and H-index point to the existence of oligopoly in the gasoline market. The entry in the market is restricted by resource ownership and high cost of starting a business. There is only one refinery in Nova Scotia. It is owned by Imperial Oil and is located in Dartmouth. This refinery supplies gasoline to all gas stations in Nova Scotia irrespective of their brand name. Thus Ultramar, Esso, Petro-Canada gas stations, to name a few, buy gasoline from the same refinery. Imperial Oil, Shell and Petro-Canada are vertically fully integrated companies, producing oil, transporting oil to refineries, refining oil and are also involved in wholesale and retail distribution. Irvin and Ultramar buy oil from market and refine before selling. There are also independent wholesalers and distributors who have their own retail outlets. Also there are small retailers in the rural areas. Some “big box” stores, which sell merchandise and food, also sell gasoline. Examples are Superstore and Canadian Tire. These gas stations, though limited in numbers, have a high sales volume because of the various schemes to attract customers. They have also lower operating costs than others because of economies of scope (joint products). The price of the crude oil is determined by the demand and supply factors in the world market. Since New York harbor market (NYMEX) is the nearest international commodity market, price there affects the price in Nova Scotia. Refineries not associated with fully integrated oil companies make contracts with oil producers for long term supply at fixed price (futures contract) or purchase on the spot market if they need supply of oil immediately. If spot prices rise in NYMEX and regulated price is lower in Nova Scotia, then the Imperial refinery in Dartmouth sells gasoline in NY rather than in N.S. Therefore, if a hurricane affects the supply of gasoline in MYMEX, then the price of gasoline rises in Nova Scotia as well. Similarly if, for some reason, like a fire in Ontario refinery, there is supply obstruction in Ontario and the price of gasoline rises there, the impact of this event is felt on the price of gasoline in Nova Scotia. Since the demand and supply in the international market determine gasoline price, the government of any province cannot regulate the price of a supplier. The jurisdiction of a provincial regulator is confined only to regulating the margins. Even though the government regulated the margins, several companies used opting out clause. At the inception of regulation all the corporate owned outlets opted out of regulation. Also all outlets owned by agents of the corporations also opted out as they did not want to change their existing contracts with the supplier. Only 50 percent of the independent marketers opted in regulation in 2006. Their number dropped to 40% in 2008 (Pinfold’s “Two Year Review”, p. 44). Overall, 101 gasoline retail outlets out of 428 (or 24%) opted in regulation. Although competition determines price in NYMEX, there is no competition among the gasoline firms in Nova Scotia. All companies in Nova Scotia buy their gasoline from Imperial Oil refinery in Dartmouth. Most of the gasoline is supplied to its destination by private trucking companies (like RST Dartmouth), rather than by corporate trucks, for reason of cost efficiency. Some independent wholesalers, like Wilson Fuels, have their own trucks. Not only companies are involved in buying gasoline from the same refinery irrespective of the brand and use contracted (and in many times the same) trucking company, they do product swapping. CTV, in its news of May 10, 2004 reported: “McTeague led the government task force in 1998-99 on gasoline pricing. He says the Bureau won’t be able to find collusion or price fixing because there is no competition in Canada’s oil industry to begin with. “He says the major oil companies share product from region to region so when you go to Petro-Canada station you could very well be buying Esso’s refined product. And he says is where the problem lies.” (CTV.ca: “Competition Bureau to investigate Gas prices”, May 10, 2004) The Nova Scotia’s big oil companies sell same types of gasoline (categorized by different octane levels), use contracted trucking companies for transporting gasoline, and swap product in different provinces, their collusive nature is evident. Even prior to regulation, price charged by different big companies on the same street gas stations was same. The price variation in distant gas stations or gas stations in different localities was the result of differences in transport cost, competition conditions, income levels and the like factors. After regulation price charged in different towns and rural areas is different. The difference after regulation results from difference in transport cost in cities and, in rural areas, also on competition, and sales volume. The competition among the gas stations prior to and after regulation has been by way of coupons, use of “Value Max” card, free coffee, air miles, credit toward grocery and the like. The regulator may high fixed the maximum and minimum price of self serve gasoline, the use of the “Value Max” card at Ultramar lowers the price of gas by 2 cents per litre. Similarly, Esso gas outlets give Aeroplan miles. These methods are done to develop customer loyalty. Unexplained change in Prices: Generally, consumers in Nova Scotia know on Thursday through radio and television how much price the regulator would change on Friday. The media generally keeps track of the market and given the formula, very much correctly predict the price for Friday. The media is also helped by price of gasoline in New Brunswick, where gasoline price is also regulated and there price changes every Thursday. In New Brunswick, the maximum price of gasoline is determined by the regulator. On May 7th, 2009, the maximum price of the regulator in New Brunswick for self serve regular gasoline was fixed at 90.9 cents per litre. The price was 89.1 cpl on 30th April 2009. The increase in price was 1.8 cpl. The media in Nova Scotia was quick to point out that price in Halifax would go up 3 cents per litre on Friday. But when the regulator in Nova Scotia set the price it was increased from 90.7 cpl for self serve and 92 cpl for full serve on May 1, 2009 to respective 96.3 and 98 cpl on May 8th 2009. The increase was 6 cpl. Considering that both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick use the price prevailing in NY harbor for calculating their base price, both convert it into Canadian dollars and both have same GST and federal except provincial tax, which is lower in New Brunswick, price increase in Nova Scotia seems excessive. If we take the fact that New Brunswick price includes transportation cost of 2.5 cents per litre maximum and Halifax price includes transportation cost of 0.3 cents, the gap between maximum regular price of gasoline between them appears to be higher. There is general feeling in Nova Scotia that prices rise quickly and come down slowly. When prices have downward spiral, in order to give fixed margins to the wholesaler and retailers, the regulator is slow to reduce prices. When prices are rising, by the same argument, they should also increase slowly. But it does not happen. For instance, on 19 February 2008, price of regular self serve gasoline in Toronto was 105.6 cpl and in Halifax it was 111.0 cpl. On 26th February 2008, price in Toronto rose to 106.1 cpl and in Halifax it rose to 117.7 cpl. The forwarding average method by the regulator is not done by a fixed formula, it is rather done by the impression of how much price should rise to keep margin same. The impression of regulator is subject to market speculations. Price Setting Authority: Another issue connected with the above analysis is that in New Brunswick the weekly price is set by New Brunswick Energy and Utilities Board, an independent body, while in Nova Scotia it is done by a branch of the government (Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations). At the inception of gasoline price regulation, it was made clear that price fixing authority would be transferred from government to the Nova Scotia Utilities and Review Board, an independent body. But so far, the government has resisted it on the ground of cost efficiency. In The Chronicle Herald interview Mr. Muir, the minister in charge of the concerned department, said: “But Mr. Muir said there will be an administrative cost if the review board takes over, and the price at the pump would likely look the same as if the government were still setting it.” (The Chronicle Herald.ca 20th September, 2008) If the price is set by an independent body, the public has greater input and the process is more open. Even if price at the pump would remain the same, the public can understand it better. Halifax and Toronto Prices In this section a comparison of gasoline prices is made between Toronto, the unregulated market, and Halifax, the regulated market. Data for this comparison has been taken from Natural Resources Canada. Figure-1 shows the rack prices of Halifax and Toronto. The lines in the graph show similar patter, Halifax having lower rack prices than Toronto. This may be due to higher demand for gasoline in Toronto than Halifax. Figure-2 shows the gasoline prices which consumer pays in both cities. This price includes all margins and taxes. The sum of margins and taxes is higher in Nova Scotia. This is reflected in the fact that Nova Scotia retail prices are higher than Toronto. However, whenever price increases in Toronto, price increase in Halifax appears to be higher. Only in one event (6 January 2009) price in Halifax was lower than price in Toronto. This was because of margin adjustment. But once that week passed, prices in Halifax were higher than Toronto again. When prices rose in Toronto because of the supply bottlenecks, Halifax prices increased more. This may be due to speculative fixing of wholesale prices by the regulator. Since the regulator does not control the supply of gasoline, the prices before tax go in synch in Toronto and Halifax. Even the retail price movement is in the same direction, the magnitude of variation depends on margin adjustment in forward averaging, which due to lack of any formula in Nova Scotia, is subject to speculation. Fig-1 Rack Price of Regular gasoline in Halifax and Toronto, March-May, 2009 Source: Natural Resources Canada Fig-2 Retail Price of Regular gasoline in Halifax and Toronto, May 2008-May, 2009 Source: Natural Resources Canada Reaction of public to price of gasoline Gasoline price regulation in Nova Scotia is a result of consumer reaction to rapidly increasing price level in the first half of 2006 when price increased from less than one dollar per litre to about $1.14 per litre. Consumers did not find any relief in the formula of regulation and the price of regular self serve gasoline increased to $1.22 per litre in early August 2006. The regulator could not and did not aim at reducing the level of prices. Late August 2006, price of gasoline fell below $1 per litre and the call for reduction in prices subsided. Again, when price of regular self serve gasoline reached $1.46 per litre in July 2008, consumers’ outcry was loud. Judging from the media interviews, consumers are pretty much comfortable with price of regular self serve gasoline about $1 per litre. The increase in price from 90 cents per litre to 96 cents per litre does not draw much attention of consumers. But as the price surpasses $1.10 per litre, consumers’ reaction gets stronger and stronger as price gets higher and higher. Conclusion The collusive oligopoly nature of the market structure in gasoline industry gives little leverage to the provincial regulator to meddle with prices, except eliminating intra-week fluctuations. The role of the provincial regulator is limited to regulating margins and taxes. Reducing taxes adversely affects government finances. Therefore, the regulator in Nova Scotia is involved in manipulating margins to stabilize prices in 7 day period. In order to achieve this objective and keep the margins constant, it uses forward averaging method, the consequence of which is higher price for the consumer at the pump. The objective of maintaining industry infrastructure has not been fully achieved as the gas stations still go out of business. A large number of gas stations have used opting out clause and have retained their existing margins and contracts with the gasoline suppliers. The regulator in Nova Scotia has not given the authority to Utilities and Review Board, an independent body, on the ground of cost efficiency. The regulator does not give details of how it arrives at the benchmark price. References: Evaluation of Petroleum Products Pricing Regulation in Nova Scotia – A Two Year Review: Prepared for Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations by Gadner Pinfold Consulting Economists, November 2008. “What’s Missing from Your Wallet? – How Gas Price Regulation Robs Consumers”, AIMS Background Paper, prepared by Bobby O’Keefe, February 2009. “Competition Bureau to Investigate Gas Prices”, CTV.ca News Staff, May 10, 2004. New Brunswick Energy and Utility Board’s data on petroleum product prices. Petroleum Products Price Regulation in Nova Scotia – A Six-Month Review: Prepared for Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations by Gadner Pinfold Consulting Economists, March 2007. Economics of the Nova Scotia Gasoline Market: Prepared for Service Nova Scotia and Municipal Relations by Gardner Pinfold and M J Erwin & Associates Inc., September 2005. Gasoline Price Changes: The Dynamics of Supply, demand and Competition, prepared by U.S. Federal Trade Commission, 2005. The Chronicle Herald.ca 20th September, 2008 Data on Toronto and Nova Scotia from www.fuelfocus.nrcan.gc.ca Data on Nova Scotia from www.gov.ns.ca/snsmr/petroleum Data from New York Commodity Exchange: www.nymex.com Data on Nova Scotia from: www.aims.ca Also data from: www.mjervin.com