Raising Expectations Is Aim of New Effort

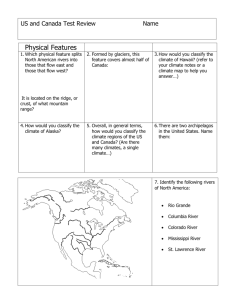

advertisement

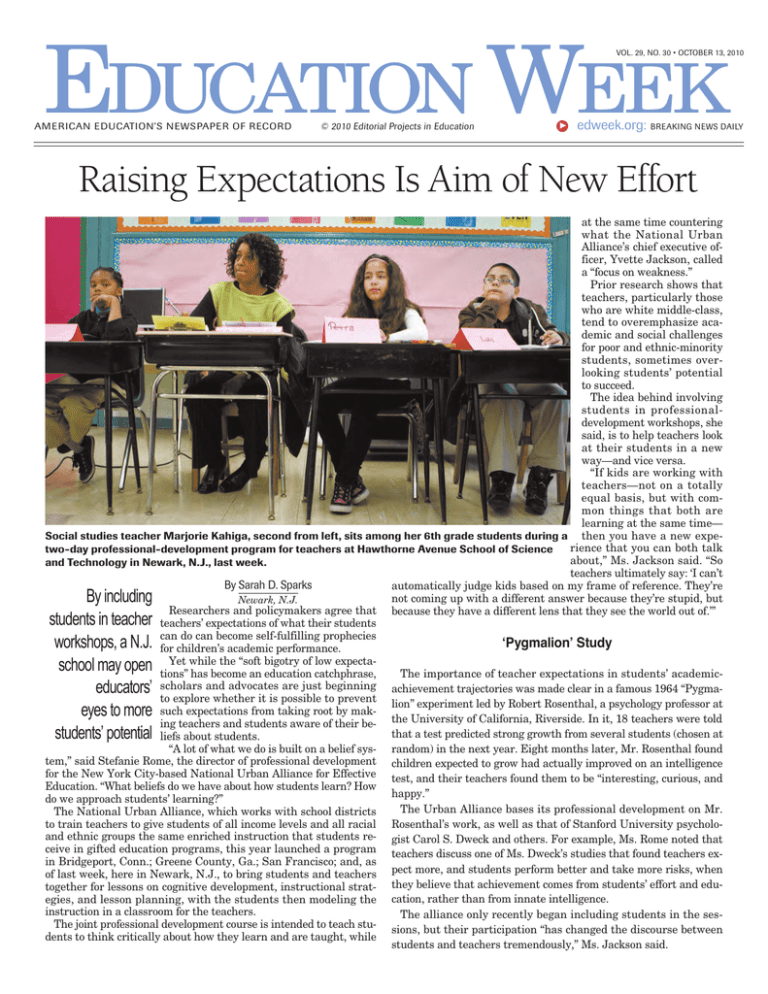

EDUCATION WEEK 6/, ./ s /#4/"%2 © 2010 Editorial Projects in Education V AM E R ICAN E DUCATION’S N EWS PAPE R OF R ECOR D edweek.org: BREAKING NEWS DAILY Raising Expectations Is Aim of New Effort at the same time countering what the National Urban Alliance’s chief executive officer, Yvette Jackson, called a “focus on weakness.” Prior research shows that teachers, particularly those who are white middle-class, tend to overemphasize academic and social challenges for poor and ethnic-minority students, sometimes overlooking students’ potential to succeed. The idea behind involving students in professionaldevelopment workshops, she said, is to help teachers look at their students in a new way—and vice versa. “If kids are working with teachers—not on a totally equal basis, but with common things that both are learning at the same time— Social studies teacher Marjorie Kahiga, second from left, sits among her 6th grade students during a then you have a new experience that you can both talk two-day professional-development program for teachers at Hawthorne Avenue School of Science about,” Ms. Jackson said. “So and Technology in Newark, N.J., last week. teachers ultimately say: ‘I can’t By Sarah D. Sparks automatically judge kids based on my frame of reference. They’re not coming up with a different answer because they’re stupid, but Newark, N.J. Researchers and policymakers agree that because they have a different lens that they see the world out of.’” teachers’ expectations of what their students can do can become self-fulfilling prophecies ‘Pygmalion’ Study for children’s academic performance. Yet while the “soft bigotry of low expectations” has become an education catchphrase, The importance of teacher expectations in students’ academicscholars and advocates are just beginning achievement trajectories was made clear in a famous 1964 “Pygmato explore whether it is possible to prevent lion” experiment led by Robert Rosenthal, a psychology professor at such expectations from taking root by making teachers and students aware of their be- the University of California, Riverside. In it, 18 teachers were told that a test predicted strong growth from several students (chosen at liefs about students. “A lot of what we do is built on a belief sys- random) in the next year. Eight months later, Mr. Rosenthal found tem,” said Stefanie Rome, the director of professional development children expected to grow had actually improved on an intelligence for the New York City-based National Urban Alliance for Effective test, and their teachers found them to be “interesting, curious, and Education. “What beliefs do we have about how students learn? How happy.” do we approach students’ learning?” The Urban Alliance bases its professional development on Mr. The National Urban Alliance, which works with school districts to train teachers to give students of all income levels and all racial Rosenthal’s work, as well as that of Stanford University psycholoand ethnic groups the same enriched instruction that students re- gist Carol S. Dweck and others. For example, Ms. Rome noted that ceive in gifted education programs, this year launched a program teachers discuss one of Ms. Dweck’s studies that found teachers exin Bridgeport, Conn.; Greene County, Ga.; San Francisco; and, as of last week, here in Newark, N.J., to bring students and teachers pect more, and students perform better and take more risks, when together for lessons on cognitive development, instructional strat- they believe that achievement comes from students’ effort and eduegies, and lesson planning, with the students then modeling the cation, rather than from innate intelligence. instruction in a classroom for the teachers. The alliance only recently began including students in the sesThe joint professional development course is intended to teach stu- sions, but their participation “has changed the discourse between dents to think critically about how they learn and are taught, while students and teachers tremendously,” Ms. Jackson said. By including students in teacher workshops, a N.J. school may open educators’ eyes to more students’ potential OCTOBER 13, 2010 Social studies and literacy teacher Bruce Fryer, right, compares journal notes with his 8th grade student Shatiana Hilarski, during Hawthorne’s two-day professional-development program. Though she called herself “Shy Shatiana” during an activity at the start of the workshop, by its end she helped teach a 5th grade class in front of Mr. Fryer and other adults. Reaching Out One such workshop was under way last week at one of the Urban Alliance’s partner schools, the K-8 Hawthorne Avenue School of Science and Technology in Newark. Over two days, teachers and middle school students learned new teaching techniques— from mnemonics to help remember children’s names to a pedagogical flowchart to improve pacing of lesson plans. The teachers helped students understand a few tricks of the trade, such as creating a call-and-response to focus class attention, while students related their class experiences to teachers. Bruce Fryer, an 8th grade literacy and social studies teacher, got into an animated discussion of class planning with a trio of 8th grade girls. Shatiana Hilarski, one of them, expressed surprise that Mr. Fryer said he works eight hours on a lesson. She said she would be more engaged in class, knowing now how much time had gone into planning it. Mr. Fryer said that learning alongside students has made him think about how he treats students, particularly boys, in class. “When I have a time like this to reflect, I think I haven’t been doing a good job of this,” he said. “Have I really been connecting?” Stepping Up The next day, Mr. Fryer and the other adults had a chance to step back and observe as the students used their new tools to create and team-teach a writing lesson on the theme of “relationships” for a 5th grade class. Q EDUCATION WEEK 2 Pairs of students walked the class through activities, from developing a taxonomy of words about relationships to writing about them and discussing their writing with classmates. “Normally [class] can get a little chaotic, but this is so structured, it’s amazing,” said Marjorie Kahiga, a 6th grade teacher, as she watched the 5th graders listen to the older students. “Most of these urban kids feel so lost,” she said. “They need to see this, to see what they can achieve.” When younger students looked confused, the other student-teachers started to fan out among the desks, answering questions and helping. Among the student-teachers was 6th grader Marc Manasse, an intent boy who entered late and was quiet during the initial work sessions. He hovered over one table, clarifying instructions and even urging the lead student-teacher to call on one of “his” students during the class discussion. Ms. Kahiga watched but stayed back. She was, as she put it, amazed. “Marc is a handful, a real handful,” Ms. Kahiga said. “Normally, in class every day I’m saying, ‘Why are you doing that?’ I’m always correcting him. Now when I see him in this opportunity, I can see what a leader he is.” The second day ended with a debriefing in which both teachers and student-teachers discussed how the students had taught and what they had learned. Marc, the 6th grader, after working with the younger class, said he decided he wants to become a teacher. “I learned that teaching is not that easy, because you have to stay on task,” he said. “You can’t just walk away from the students and expect them to learn; you have to keep on them and make sure they get things done.” It remains to be seen whether the program, which will cover 10 such workshops with different students this year, will lead to improvements in student performance. The Urban Alliance introduced the change in the fourth year of a five-year grant through the federal Striving Readers program, and the Rockville, Md. based Westat, the grant’s evaluators, have yet to review it. But participating teachers said including students in the session was eye-opening. “Honestly, as teachers, we can shut them out of the learning process,” Ms. Kahiga said. “They need to be part of the learning process.” _______________________________________________________ Reprinted with permission from Education Week, Vol 30, Issue 7, October 13, 2010, by IPA Publishing Services, 800-259-0470. (12040-1110) For web posting only. Bulk printing prohibited. Editorial & Business Offices: Suite 100, 6935 Arlington Road Bethesda, MD 20814 (301)280-3100 Fax Editorial (301)280-3200 Fax Business (301)280-3250 Education Week is published 37 times per year by Editorial Projects in Education, Inc. Subscriptions: U.S. $79.94 for one year (37 issues). Subscriptions: Canada: $135.94 for one year (37 issues). _______________________________________________________ National Urban Alliance 33 Queens Street Suite 100 Syosset, NY 11791 (800)NUA-4556 or (516)802-4192 On the Web: www.nuatc.org