School resources and schooling outcomes in a frontier society: evidence... Columbia, 1900-1920

advertisement

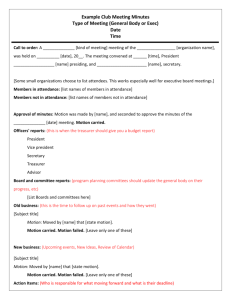

School resources and schooling outcomes in a frontier society: evidence from British Columbia, 1900-19201 May 2008 Mary MacKinnon (McGill) Chris Minns (LSE) DRAFT For the CNEH sessions at the CEA Conference 1 We thank SSHRC for financial support and François Claveau for research assistance. Thanks are also due to Kris Inwood, Tim Leunig, and participants at the Canadian Economics Association meetings in Halifax, and seminar participants at Queen’s (Kingston), McGill, Warwick, and Western Ontario for comments on earlier versions of this paper. Introduction A central debate in the economics of education is the role of school and teacher quality in human capital formation. Parents and governments often use input indicators to assess the merits of different schools, but evidence on whether greater quality or quantity of inputs are associated with better schooling outcomes is decidedly mixed. Concern about school quality is not a new phenomenon. Professional educators in North America have argued about how schooling should be supplied for over 150 years.2 This paper uses early 20th century administrative data from public primary schools in British Columbia, Canada, to assess the importance of school and teacher characteristics in shaping primary school outcomes. The Annual Reports of Education (ARE) for British Columbia provide abundant information about provincial public schools. In this paper, we focus on explaining attendance.3 Attendance is an intermediate input in the production of education.,School characteristics that improve or hinder attendance likely have an impact on continuation to more advanced education. Children with irregular school attendance would likely acquire less human capital for any given years of schooling. Simply sharing a classroom and teacher with children who came to school only occasionally probably slowed the progress of the average child. The ARE record detailed information on factors that may play an important role in explaining attendance patterns: pupil enrollment, number of teachers and their gender, the teaching certificates the teachers held, and their rates of pay.4 To our knowledge, this is the first direct evidence on the relationship between school 2 3 4 For histories of 19th century education in Massachusetts and New Jersey, see Kaestle and Vinovskis (1980), Katz (1968), and Burr (1942). Wilson, Stamp, and Audet (1970) provide an overview of Canadian educational history, while Johnson (1964) focuses on British Columbia. For most years, there is also information on the number of pupils passing the high school entrance exam. This measure is harder to interpret. Having any pupil pass the exam was a rare event for smaller schools. By the 1920s, the larger urban elementary schools were able to recommend strong candidates for high school admission without examination. It is possible that as high school attendance became a more frequent activity for teenagers, the passing standard for the entrance exam fell. It is hard for us to work out years of teacher experience in the BC system. The records generally give teachers’ first initial and surname, and there are many teachers with common Anglo-Celtic surnames. We have just begun to incorporate information on capital expenditures per school. 1 inputs and educational outcomes prior to the 1920s.5 British Columbia was settled later than most of North America, but conditions at the time of settlement were roughly similar to other parts of the continent in the later 19th century when many school systems were in rapid expansion. The economy of British Columbia fits well into the classic paradigm of late 19th and early 20th century economic development on the North American frontier: scarce labour, abundant resources, large-scale inward migration in response to wage opportunities, and few pre-defined public institutions, particularly away from established urban areas. The administrative data we have assembled allow us to explore how schooling arrangements evolved during settlement, and whether the changing characteristics of schools had a role to play in raising educational outcomes. Given the rapid pace and diffuse nature of settlement in British Columbia, educators were faced with a difficult policy choice: should the priority be to improve the quality of existing schools, through age-grading, reducing pupil/teacher ratios, improving teacher certification, and improving the physical infrastructure of schools, or to improve access by building new schools to serve pupils a long way from existing schools? The quality/access tradeoff is at the heart of a debate over education policy in present-day developing economies. Hanushek (1995) argues that the expansion of “low-quality” schools in developing economies does not lead to improved outcomes, while Kremer (1995) counters that improving access should matter at some margin, once basic quality improvements such as textbook supply have been undertaken. Educators in early 20th century British Columbia favored expanding the availability of graded, multiple teacher schools with more highly trained teachers in charge. At the same time, there was strong political pressure to provide 5 Several studies have examined the importance of demographic and personal characteristics in explaining 19th century attendance patterns (Galenson 1995a, 1995b; Katz 1978). Others have considered the implications of early 20th century school quality at a more aggregate level. Robert Margo’s (1986, 1987) studies of racial inequality in schooling provision in early 20th Century United States examine the relationship between individual-level child literacy and county-level attendance and country-level measures of education resources. David Card and Alan Krueger (1992) relate state-level differences in black and white schools to the earnings of adult cohorts in post-1940 US Census data. 2 some sort of school near every settlement. Did attendance rates rise as more resources were put into primary schools? British Columbia in the North American Picture School attendance in both Canada and the US rose in the early twentieth century. For Canada, census estimates suggest a greater increase in the proportion of children at school than do administrative records compiled at the school level (Table 1); both show a substantial rise occurred between 1911 and 1921.6 BC had a fairly high enrolment rate at the beginning of the period, but experienced only a modest increase over the next thirty years. Across the country, the number of days the typical pupil attended class increased sharply, and BC shared in this trend. Even in 1900, BC had relatively high attendance rates by standards in the rest of the country. This was likely due to the concentration of population in urban areas and the relatively mild winters in the heavily populated areas.7 The opportunities for children to master the elementary school curriculum must have been far greater around 1930 than around 1900, as much or more because in the years when they attended school, they attended most of the time than because they were registered for more years. The average rates in Table 1 conceal substantial variations within provinces. In 1900, a quarter of British Columbia primary schools had attendance rates below 52 percent. By 1920 attendance had improved at almost all schools, but attendance rates in the bottom quarter were below 70 percent – in other words, the average pupil at these schools still missed almost one day in three. School attendance rates in British Columbia were well below comparable figures for the eastern and Midwestern United States a generation earlier. Galenson (1995) reports that 6 The school-level records indicate 130 – 215,000 MORE pupils at school than the census counts. When pupils changed school, they were likely counted a second time in the administrative records. It may also be that parents answered “No” to the question about school attendance for many of the pupils with the weakest attendance. 7 The high attendance rate in Quebec was likely largely caused by the low enrolment rate. In the 1920s, had enrolment rates in BC risen more, quite likely the attendance rate would have dropped somewhat. 3 1860 attendance rates for children aged 7 to 11 were over 90 percent in urban Massachusetts, and over 80 percent in Chicago. It is likely that median attendance rates in British Columbia in 1900 were somewhat below Chicago in 1860, and that attendance rates in the lower tail of the distribution were well below Chicago’s less-attended schools. A range of factors either entirely or largely outside the control of educators could have contributed to the rising attendance rates shown in Table 1. With improved transportation networks and higher population density, it was easier for children to get to school. With better public health measures and lower child mortality rates, school-aged children may have been healthy enough to go to school more days of the year, and their parents would have had less reason to keep them away from a potential source of infectious disease. For families least interested in sending their children to school, the hiring of truant officers and the enforcement of school attendance and age of employment laws may have mattered. Educators did have some control over the availability of schooling across the province, and implemented regulations regarding the training and employment of teachers. As a result, there was scope for schooling to respond rapidly to the demands of parents, or to the changes in numbers of school-age children caused by rapid population change. In most of North America, public schools were mainly financed through local taxes, with provincial or state government grants paying for only a small portion of expenditures. British Columbia was unusual in that it started with a highly centralized system. This was probably part of the legacy of starting late – by the 1870s, setting up public schools was not controversial. Migrants expected schools to be available pretty much when they arrived, even though a local government might barely exist. Costs and responsibilities were gradually downloaded, first to cities and then also to rural municipalities. Up to the 1920s, the provincial government paid at least a third of all school costs. (Annual Survey of Education 4 in Canada, 1926 (DBS, 1928), p. 103).8 Thus there was considerable scope in BC for the structure of provincial grants to influence how the schools were structured, probably much more so than was typical across North America. From 1893 to 1905 the main grants to cities were based on numbers of pupils attending school: this of course encouraged very large class sizes (Johnson, 1964, p. 93). From 1906, the grants were based on the number of teachers employed. In Vancouver, the grant paid roughly half the cost of hiring a teacher. (Johnson, 1964, p. 95). Population growth and the spread of schooling British Columbia experienced rapid population growth in both rural and urban areas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Between 1891 and 1921, the provincial population rose more than fivefold to 524,000; the population aged 5 to 19 rose more than sixfold. Population grew rapidly in both urban and rural areas, with just over 25 percent of the population living in urban areas throughout the period. Settlement took place in a region where public schools were initially few and far between. In 1871, there were only 15 schools in the entire province. Much of British Columbia has rugged terrain, and in the early 20th century many settlements were physically remote from all other inhabited places. Some settlements were accessible primarily by water, and school inspectors in rural areas commented on how poor road access hindered attendance.9 One reason for sporadic attendance in much of the province, therefore, may the unavailability local schooling. Parents of children residing more than a couple of miles from a school may have been unwilling or unable to relocate to encourage regular attendance. Given the geographical constrains and the stresses created by rapid population growth, school inspectors faced the age-old challenge of how to spend their budget. Was it 8 9 In the early 1900s, the proportion was close to 2/3. The report for Anarchist Mountain school in 1904 notes that “low attendance [is] said to be caused by sickness and bad roads.” Comments on Rock Mountain school in the same year include “low attendance caused by stormy weather and bad roads; many pupils enrolled live at considerable distance from the school.” 5 better to invest in additional schools, or to expand enrollment at existing schools? Was it preferable to hire a larger workforce with a higher proportion of less-educated teachers in order to have smaller classes and/or more schools, or did investing in a smaller workforce of better-educated (and better paid) teachers have greater return? The school inspectors wanted both higher attendance rates and more learning in the classroom. They saw the limitations of minimally educated teachers, especially in one-room schools. They wanted graded schools wherever possible, with all teachers possessing at least a 2nd class certificate (partial high schools plus a full year of normal school attendance). What actually happened was a rapid expansion of both graded and one-room schools. In 1900, the province had 5 high schools, 38 graded schools – primary schools with multiple classes and teachers – and 264 common (one teacher) schools (Table 2). Figures 1 and 2 map enrollment in common and graded schools in 1901. As there are often several schools in the same approximate location, we have calculated common and graded enrollment at each tenth of a degree of latitude and longitude. Marker size corresponds to the number of enrolled pupils at each location. Population, and enrollment, was concentrated in the Vancouver area; on the mainland, with settlement follows the Fraser river as it moves inland from the coast. Graded schooling was readily available near major population centres, in particular the west coast cities of Nanaimo, Vancouver, and Victoria. The majority of British Columbians did not live in a substantial town or city, however, and schools of any type were often few and far between in the northern and interior regions of the province. Access to high school was particularly limited in 1900: there were only 5 public high schools in the province, and students away from major and semi-major urban areas (Vancouver, Victoria, Nanaimo, New Westminster, and Nelson) had to travel a substantial distance and board in town to pursue a secondary education. Over 40 percent of primary school pupils attended a school more than 5 kilometers from the nearest high school. 6 Figure 2 maps primary enrollment in 1921. There was a rapid expansion of all types of schools over the period, with numbers rising to 53 high schools, 292 graded schools, and 612 common schools. Schooling density rose strongly in major urban centres, but outlying parts of the province also gained improved access to education with the spread of common schools to areas of recent settlement. There was a large increase in the geographic availability of secondary schooling by 1920 (Table 2, last row). However, over 15 percent of primary school pupils were still studying more than 5 miles from the nearest high school; in districts with limited urban settlement, it is almost certainly the case that a substantial fraction of children would not be able to travel to the nearest high school from their home. School and teacher characteristics The Annual Reports of Education (ARE) for British Columbia provide abundant information about provincial public schools. As well as information about attendance rates, the ARE also record factors that may play an important role in explaining attendance patterns: enrollment, number of teachers and their gender, the teaching certificates the teachers held, and their rates of pay.10 We have currently put records from 1900/01, 1905/06, 1910/11, 1914/15, and 1920/21 into digital form.11 In 1900, common schools were five times as numerous as graded schools in B.C., but taught only just over a third of primary school students (Table 2). While the total number of common schools continued to rise until 1920, the number of graded schools rose more quickly, so the share of pupils in common schools fell to about 15%. Graded schools often 10 11 The records of the ARE give enrollment (both sexes), actual attendance, teacher name, and the salary of the teacher for every classroom in every public school in the province. The enrollment totals are for all children enrolled in a particular class at any time during the academic year. Thus some pupils are counted twice if they change classes or schools. Attendance figures show the total number of pupil-days in the academic year. The total number of school days is also reported. We chose the academic year 1914-1915 due to the poor condition of the 1915-16 copy of the BC Sessional Papers in the British Library of Political and Economic Science. 7 replaced common schools in small urban areas in the province. Common schools generally divided pupils into up to three “classes” based on age and academic skills, but the same teacher was responsible for instruction (and simultaneous monitoring) of all pupil groups. It is not difficult to imagine the challenges facing single teachers in large common schools, both in terms of maintaining discipline, and simultaneously teaching pupils at different levels of academic development. Some parents may have perceived common schools, and in particular common schools with large numbers of pupils, as having rowdy classrooms that did not provide sufficient academic stimulation to make attendance worthwhile. Some inference on the dispersion of age and ability in early 20th century schools can be made from the ARE listings of the number of students following each “reader” in every academic year. Reader divisions were not perfectly correlated with age, but it is the best available approximation for academic grade divisions within the school. Between 1900 and 1920 there were seven different levels of primary school reader, from First Primer to Fifth Reader12. In many one-room schools, pupils are widely distributed across all seven readers, with both the most junior grades (First and Second Primer) and the most senior grades (Fourth and Fifth reader) having twenty to thirty percent of the student population. Graded schools and common schools also differed in other important characteristics. Simply having at least two teachers on staff permitted back-up when one teacher was absent. Head teachers in larger graded schools took on responsibility for administration and discipline.13 An experienced and well-educated principal could help train new teachers. Table 3 summarizes attendance, school, and teacher characteristics from the ARE for primary schools at the beginning and end of our period of study. We calculate average class size from recorded enrollment and number of classes. The largest classes were always found 12 It should be noted that Fifth Reader was used extensively in 1900, but in the other years, few or no pupils were above Fourth Reader. 13 Perlmann and Margo (2001) find that in early 20th century US elementary schools staffed mainly with female teachers, the (male) principal was responsible for discipline. This is also the case in British Columbia, although in smaller graded schools the principal generally taught the most advanced class. 8 in the graded schools. In 1900-01, there were over 50 pupils per teacher in these schools, but this dropped to 36 by 1920-21. One-room schools had much lower pupil-teacher ratios on average, but about 25 percent of these schools had one teacher responsible for 60 or more students. Reduction in class size was at least somewhat influenced by provincial government policy. In 1906, the revised Public School Act decreed that classes of more than sixty were unacceptably large; by 1922 they were setting the break at forty (p. 96). We will show below that these class size thresholds appear to have mattered in determining when one-room schools hired an additional teacher and became a graded school. There was a clear relationship between class size and school type. When an oversubscribed common school was “upgraded” to graded school status by taking on an additional teacher, class size fell, but where population was rising rapidly, after two or three years the reduction in class size was often fairly modest.14 The average teacher in a graded school taught many more children than the average teacher in a common school, as few common schools were on the verge of being converted into graded schools (Table 3). It was almost certainly easier to teach a larger group of children aged 8 to 10 than a smaller group aged 6 to 13. The education reports give enrollment by sex of pupil, from which we derive the sex ratio. Attitudes towards education and out-of-school opportunities may have differed between boys and girls, or the parents of boys and girls. Unfortunately, we do not know sexspecific attendance rates. Throughout the period, the majority of high school students (54-64 percent) were girls, while in the primary schools the sex ratio moved towards parity between 1900 and 1920. The number of days the school was in session (days when some teaching took place) 14 The steps to add a second teacher and classroom to an oversubscribed common school are not clear. Trustees probably lobbied the provincial government. Consistent with statements in the 1906 Public School Act, the data suggest that once a school had 60 pupils, an additional teacher was added within a few years. 9 is also reported in Table 3.15 Variance in the number of session days was often caused by teacher absenteeism. This reflects economic conditions (teachers leave for better paid whitecollar occupations elsewhere, and are difficult to replace on short notice), and other shocks that prevent schools from operating (for example, bad weather or an outbreak of an infectious disease).16 Some schools were opened part way through the year, or added an extra classroom. It is unclear if session days and attendance rates should be related, but schools with shorter terms would presumably get less teaching done, which could have significant effects on high school examination performance.17 Average days in the school year fell over the period. The variance in the days schools were in session is greater for common than graded schools, and greater in the earlier years. Bad weather and other disturbances were more likely to lead to school cancellations in remote one-room schools, although common schools had about the same average number of teaching days as graded schools. Around 1900 it was also probably harder to replace teachers on short notice than was true twenty years later. Teaching in graded and common schools also differed because the typical teacher in a graded school was better educated (Table 3). While the requirements for teacher certification changed over time, a third-class or temporary certificate always implied very limited academic preparation and little or no formal teacher training.18 British Columbia school inspectors routinely complained about the relatively high proportion of teachers, particularly in common schools, practicing with third-class or temporary teaching certificates.19 It is 15 From 1900 through 1914, the reports list the prescribed number of days for the class or school – some parts of the province had school years that were a few days longer or shorter than average. For graded schools, reported session days is an average across all divisions in the school. 16 The inspector comments suggest that weather and disease were important factors in explaining attendance, and whether schools remained open. ***Find nice example from reports!*** 17 If a school opened late because there was no teacher for the first two months of term, attendance may have been abnormally high once the teacher arrived. However, if a school was closed for some weeks because of an epidemic, there may have been very low attendance in the weeks just before and after the closure. 18 The first Normal School in BC opened in 1901, so the early certificates could not require formal teacher training. 19 Inspectors were dismissive of the classroom abilities of such teachers: “If to teach successfully a 10 something of a surprise to find any university-educated teachers in common schools (holders of academic certificates) and a fair sprinkling of teachers with qualifications clearly above what was seen as a reasonable minimum (which was always defined as a second-class certificate). The increased tendency to vary teacher pay by qualification, which became more feasible as local areas had to take on responsibility for paying teachers’ salaries, may have helped to drain the common schools of their better qualified teachers. Data on student and staff numbers and salaries can be combined to give a sense of the per-student labour cost of teaching in the different types of primary schools. The per (enrolled) student teaching cost in graded schools was about sixty percent of that in common schools, and attendance was 8 to 12 percent higher. As in the other parts of North America, school teaching in British Columbia was increasingly feminized between 1900 and 1920. Men were much less likely to be found in one-room schools in 1920 than in 1900, and were concentrated in the high schools or as principals of graded schools (Table 4). Women teachers were less likely to hold academic or first-class certificates, and received lower salaries as a result. In 1920, both graded and common schools were run by staff with fewer formal qualifications but more on-the-job experience (Table 4). Neither type of primary school had as large a proportion of academic or first-class teachers in 1920 as in 1900 (Table 3). Even adding in the high school teachers, the share of “well-educated” teachers in 1920 was about the same as in 1900. Explaining Attendance Rates The data in Table 3 show graded primary schools had significantly higher attendance rates. This may not mean that adding a second teacher, and in doing so turning a common rural school of from twenty to thirty pupils, with its multiplicity of classes and subjects, is a tax on the ability, energy, tact, and generalship of the best Normal trained teacher, where will the young, inexperienced, and untrained teacher appear? They are simply helpless… They are simply ‘keeping school’.” *** Nail down where this reference comes from *** 11 school into a graded school, will necessary lead to a rise in attendance. Differences in other school characteristics documented in Table 3 may explain much of the attendance gap. Graded schools also were mainly in locations where pupil attendance rates would be higher whatever type of schooling on offer. We estimate OLS models of attendance rates to control for a range of characteristics that may affect school attendance rates. Column (1) of Table 5 lists the results of an attendance regression for over 2000 primary school attendance observations for which we have complete information, including the location of the school. The explanatory variables include school and teacher characteristics (summarized in Table 3) that are potentially relevant to parental or student attendance decisions. We also include a series of variables related to school location. The first is a dummy variable indicating whether a school is at least 5 kilometres from the nearest alternative school. This is a rough proxy of the catchment area of a school; we are not able to map the population distribution of the province against individual schools, but schools that are distant from all other schools will be the closest school for any potential students living at least a couple of miles walking distance. We also include a measure of whether a school is more than 5 kilometres from the nearest high school. Greater costs of continuing in education will inhibit attendance if one of the reasons for coming to school is to acquire the knowledge necessary to continue on to secondary school. We do not know the population of small villages and settlements in the province, and are therefore unsure of the size of the relevant local labour market for each school. We have constructed a proxy for market size using records from the Report of the Postmaster General printed in Sessional Papers of Canada. The Postmaster’s Report contains an annual list of all post offices in Canada, and the revenue collected by each post office. We attach local post office revenue to any schools that are within one-tenth of a degree of latitude and longitude of 12 a post office.20 Three dummy variables are used to pick out variation in market size: no local post office, local post office with over $1000 of annual revenue (in constant 1901 dollars), and local post office with over $5000 of annual revenue (constant dollars). The regressions also include dummies for the year of observation. Table 5 shows how these characteristics correlate with attendance, and how the link between school type and attendance is altered by the introduction of these controls. The first finding is that teacher pay and attendance are positively correlated. We do not propose to make a strong causal interpretation of this result. Better pay may be a proxy for unobserved teacher qualities, and may motivate teachers to work harder, but it is also likely that attendance was a determinant of teacher salaries. The 1905 School Act gave municipal school boards authority over salaries, and the school inspectors claim that outcomes were a leading consideration in setting pay for returning teachers.21 Class size is also strongly correlated with attendance. Reducing class size by ten (one standard deviation of common school class size in 1920) is associated with 2 percent greater attendance. This coefficient is less likely to suffer a downward bias (meaning that the true effect is smaller in magnitude than what is reported) due to reverse causality or unobserved heterogeneity, as unmeasured factors that cause schools to have higher attendance rates are also likely to lead to greater enrollment.22 Student sex ratios and the length of the school year are both negatively related to attendance rates. The first finding may indicate that boys and girls have different ageattendance profiles, but we are unable to verify that with the British Columbia data. One possible explanation for the second finding is that parents and children targeted a certain 20 In practice, this means that a school is allocated the market size of the largest post-office within 9 kilometers of the school. 21 However, results from annual cross-sections give no suggestion that the pay/attendance correlation is stronger after 1905 than before. 22 We have never found a comment in the Inspectors’ reports suggesting that because attendance was improving, a teacher could not handle as many pupils in a class. 13 number of days of school, regardless of the number of days a school was actually open to students. This would lead to a mechanical increase in attendance rates without any attendance response to unexpected school closure.23 Another possibility is that new schools, which may be open only half or three-quarters of the usual school year, initially have higher attendance rates as the most enthusiastic parents are the first to enroll their children. The attendance data support this view. Schools in the bottom quartile in terms of session days (in 1905, this would be schools with less than 190 days in session) have attendance rates about four percent higher than the average of the top three quartiles. Teacher characteristics appear to have only a modest impact on attendance. In particular, we do not find a meaningful relationship between teacher qualifications and attendance. Table 5 reports small, insignificant coefficients on the presence of a teacher with at least a second-class certificate. Alternative regressions generated similar insignificant coefficients for other qualification categories. Schools that were a long way from a high school had significantly lower attendance, all else equal. This coefficient is probably indicating that it was harder to keep older children in school when there was no local option for secondary schooling. Schools with larger catchment areas (which we infer from distance to any alternative school) also had somewhat lower attendance rates.24 As the school inspectors wrote, distance was a barrier to attendance. Teachers, parents, and pupils, in primary schools without local high schools may have seen primary education as being terminal, and as a consequence not put too much effort into lessons for older children. The variables for post office revenue suggest there was some relationship between 23 A recent article by Pischke (2007) finds that length of the school year and later earnings are uncorrelated in contemporary Germany. His interpretation is that students who were exposed to short years adjusted their human capital accumulation accordingly. The attendance impact of the length of the school year that we find is consistent with this possible adjustment process. 24 The coefficients on distance to other primary schools are roughly similar if we exclude the high school distance variable – in other words, distance to a high school is not absorbing the effect of distance to another primary school. 14 economic activity and school attendance. Schools only open for part of the period (col. 1) had much better attendance rates if there was a fairly active post office in the area. When we look only at schools open in all years, we find a small negative effect for schools in places without any post office. Places with schools already open in 1900 must have been settled early, and probably had relatively good road networks. After adding regression controls, school structure retains a strong relationship to attendance rates, as it did in Table 3. Column (1) suggests that graded schools had about 10 percent higher attendance than common schools with similar characteristics. It is possible that schools in areas with high attendance, perhaps due to unobserved characteristics among the local population, were more likely to receive funding for an additional teacher. Columns (2) and (3) probe this possibility by examining only the sub-sample of schools for which we have data for all five years. The coefficient on graded schools in this sample drops (column (2)), and drops somewhat more when school fixed effects are introduced (col. 3), but it still has a clear effect. This result gives us some confidence at the first pass that “grading” a school had a substantial impact on attendance, all else equal. Graded schools and reader distribution Adding a second teacher appears to have had a substantial effect on school attendance. The results above, however, do not tell reveal which pupils were more or less affected by grading. If graded schools were able to offer more focused training to older children with potential to enter high school, we might expect to see relatively high attendance in schools with more pupils in the upper reader categories. On the other hand, graded schools may have been especially attractive to the parents of young children, who may have received little attention in a school where most of the teaching time was devoted to children above the age of 10 or 12. A longer walk to school would have been more difficult for younger children, so schools with many young children probably had lower attendance rates in bad 15 weather. We use information in the ARE on school subject readers to explore the link between grading, age and reader distribution, and attendance. As discussed earlier, pupils are spread over seven classes of reader, which correspond to academic development, and roughly, age.25 Table 6 presents results from attendance regressions similar in form to Table 5, but with the addition of two variables measuring the share of pupils in junior reader categories (first and second primer) and in senior reader categories (fourth and fifth reader). The first column of Table 6 estimates the regression for the full sample of primary schools from 1900 to 1920. [why do we lose a few observations, relative to Table 5, col. 1? About 47 gone] The coefficient on junior reader share indicates that attendance rates were significantly lower in schools with larger shares of primary reader pupils. Raising the share of junior pupils from 30 to 50 percent (which is about equal to going one standard deviation from the mean) would be predicted to reduce attendance rates by two percentage points. The graded coefficient falls by about .02, but remains positive, significant, and substantial. Columns (2) and (3) break out the regression in column (1) into graded and common school subsamples. Of particular interest here is the difference in the junior share coefficient between these two groups. A higher share of junior readers led to lower attendance in common schools, but had little systematic impact in graded schools. A plausible interpretation of this pattern is that graded schools were more attractive to parents of young pupils. One-room schools may have had particular difficulty allocating teacher time to junior readers, given that the teacher also had to deliver more advanced content and enforce 25 Children who attended school rarely probably took longer to complete the first two books (the primers), but their parents or older siblings may have been able to help them with this level of work at home. They were likely to never get into the “senior readers” category. Thus “junior readers” is probably a closer approximation to “young children” than “senior readers” is to “older children.” We have also collected the number of pupils enrolled in advanced subjects (algebra, bookkeeping, geometry). The proportion of students following these subjects was somewhat higher in graded schools than common schools, but by 1910 less than 5 percent of pupils were studying any of these subjects in graded schools. We were unable to find any meaningful correlations between the availability of mathematics or bookkeeping and primary school attendance. 16 discipline among older children. If junior pupils were the most neglected in traditional one room schools, it stands to reason that schools with set class divisions and multiple teachers would be particularly attractive to parents of pupils who had just entered formal education. The Transition from One-Room to Graded Schools The regressions in Tables 5 and 6 do not prove that grading a school caused attendance to rise, although they do demonstrate that the higher attendance rates in graded schools were not simply a result of other characteristics more commonly associated with graded than common schools. It may be that a few large graded schools in the cities of British Columbia are driving the regression results, with small two-room schools having similar attendance levels to common schools. We use supplementary data collected from the ARE to trace groups of schools over time, to see what happened when common schools expanded into small graded schools, and how this compared with schools that did not expand. Panel 1 of Table 7 summarises attendance and class size outcomes in schools that added a second teacher between 1906 and 1910. When common schools became graded schools, class size dropped and attendance rates rose.26 Figure 5 shows annual average class size and the average attendance rate by year for schools that changed from being one teacher to two teacher schools at some time between 1906 and 1910. “year” on the X-axis can be any year from 1906 to 1910 – it is the year when the change took place.27 Almost all the schools that experienced this transition had operated for four years before the change, and continued to operate for at least another four years. Class size and attendance rates have been averaged for all schools that can be traced.28 Schools adding a teacher experienced a sharp drop in average class size the year when the second teacher was hired. Rising enrolment generally triggered the hiring of the second 26 We have repeated this analysis for other intervals, with broadly similar results. We collected additional annual data for this subset of schools to generate this figure. 28 We have made similar calculations for the interval between 1900 and 1905, and the results are much the same. 27 17 teacher. Typically, class size rebounded somewhat in the two or three years following the hiring of the second teacher – a second teacher was probably hired in areas where enrolment was expected to continue to rise. If adding a second teacher caused a school to function better, we would expect any impact of quality of the school on enrolment to have taken some time. What is most striking in Figures 5 is the sharp increase in average attendance rates in the year when the second teacher was hired. The first year effect on attendance rates was not fully maintained, but average attendance rates in the next four years were clearly higher than the average attendance rates in the four years before the school became a graded school. Figure 5 suggests that teachers were added in response to enrollment, not attendance rates, and that attendance responded in short order to the grading of a common school. A two-teacher school was often in a new or expanded building. It may be that improvements to facilities were easily observed by parents, and that expectations of an improved environment, rather than improved pedagogy associated with age grading, generated attendance improvements in schools adding a second teacher. Up to 1910, building expenses for public schools can be identified in the Public Works Report of the Sessional Papers of British Columbia, and we have tracked major expenditures of $1000 or more for all schools considered in Figures 3.29 Between 1905 and 1910, 15 of the 24 schools receiving a second teacher also had a major building expense that roughly coincides with the arrival of the second teacher.30 The 15 schools that added a teacher with contemporaneous building expenditures saw a 18 percentage point increase in attendance rates (from 59 to 77 percent), versus a 16 percent increase (from 59 to 75) for the 9 schools that added teachers without any accompanying physical expansion. The number of schools we can compare in this way is 29 From about 1910 onward, a large share of school construction expenses are reported by municipal district, rather than by individual school. The municipal districts of Burnaby and Point Grey, for example, receive large grants regularly after 1910, but it is not possible from the Sessional Papers to determine at which schools (and it what form) spending took place. 30 We consider building expenses to coincide if expenditure was recorded within a year of the arrival of the second teacher (i.e. 1902 to 1904 for a school adding a second teacher in 1903). 18 small, and schools may have been able to finance minor building work that was not reported in the Public Works accounts. Wherever we can trace capital expenditure, however, we find little evidence that schools that built new facilities to house additional classrooms had better attendance outcomes than those that just added a teacher. The focus above is on what happened in the groups of schools that did receive additional resources in the form of a second teacher. How do changes in outcomes for these schools compare to common schools that did not receive funding for second teachers? Ideally, we would compare places that were much the same in all respects except that some moved from common to graded school status, while others retained their common school. In fact, we know that the areas where common schools remained, areas where schools were always graded, and areas where a transition took place were different. We are unable to quantify many potential differences – in particular, we do not know much about the economic and demographic characteristics of residents in school catchment areas. We use two pieces of information to construct comparison groups: common school enrolment, and market size, as approximated by post office revenue. Comparison groups cut on these dimensions can be argued to be close or above the enrolment threshold to be considered for an additional teacher, and may have roughly similar labour market opportunities, to the extent that market the size and wage and employment possibilities are correlated. Panels 2 and 3 of Table 7 display comparison groups of common schools that did not receive additional teachers between 1905 and 1910. Panel 2 tracks outcomes for the entire group, while Panel 3 considers schools with at least 30 pupils enrolled in 1905. These cutoffs mean that the schools in Panel 3 have roughly similar average class size and market size to common schools that did receive second teachers between 1905 and 1910. Attendance increased much more slowly in the always common schools in Panels 2 and 3, despite relatively small classes. Postal revenues indicate that schools that received second teachers 19 were in markets with somewhat faster growth between 1905 and 1910, but the difference is not enough to suggest that educators expanded schools only in areas where they anticipated significantly faster population growth. Panel 4 tracks outcomes for schools that are graded in both 1905 and 1910. This group had higher attendance rates throughout, but smaller increases over time than the “just graded” group of Panel 1. Clearly, schools graded as early as 1905 were generally in large towns or cities. Within urban areas, improvements in attendance were modest. In the final panel, we focus on the smaller “always graded” schools. Here again, we see a modest rise in attendance rates. Taken as a whole, Table 7 suggests that the addition of a second teacher did accelerate attendance rates above the expected outcome in similar schools that were not allocated additional teachers, or in schools that already had at least two teachers. Another way to think about the impact of grading schools is to compare the impact of the addition of a second teacher in an existing school to the addition of a nearby second common school. This would have been a genuine policy choice – was it better to open a new common school so that some children would not have to travel as far every day, or to introduced grading? We have identified all cases between 1905 and 1910 where a common school more than 3 kilometres from the nearest school at the beginning of the period was less than 3 kilometres from the nearest school (either graded or common) at the end of the period. Between 1905 and 1910, attendance rates in this group of schools rose 7 percentage points (N=11), compared to 11 percentage points for common schools receiving a second teacher (N=19).31 The addition of a nearby school did appear to raise attendance rates in affected common schools.32 This may reflect reduced commuting distances for pupils, a positive impact of some school choice on performance, or improved road networks and other benefits 31 Again, we use the figures for 1905 to 1910 to illustrate findings that hold for other intervals that we have looked at. 32 The entire population of always common schools have attendance rate increases of 2 percentage points between 1900 and 1905 (N=140), and 1 percentage point between 1905 and 1910 (N=140). 20 of denser settlement. That the increase is smaller than for schools hiring second teachers suggests that there were important economies of scale associated with age grading that were not matched by adding to the network of common schools. Graded schools and local common schools: were there spillovers? Adding a second teacher had a substantial impact on attendance in the newly graded school, relative to common schools that continued to employ only one teacher. The grading of a common school may have had an impact on the performance of nearby common schools and the availability of primary schooling for pupils in outlying areas. If graded schools provided greater quality of schooling, it is possible that the best (and most regular) pupils in a region were attracted to schools adding second teachers. This would be at the expense of outlying common schools, which would be left with smaller classes, but with a selection of pupils less committed to education. If the allocation of a second teacher to a school came at the expense of outlying common schools, the prospects for pupils close to the graded school would be favoured at the expense of remote pupils for whom the cost of attending the graded school was too high. Tables 8 and 9 trace changes in attendance rates by distance to a graded school at the beginning and end of two intervals: 1900 to 1905, and 1905 to 1910. We have made similar calculations for 1910 to 1914 and 1914 to 1920; the results are similar, and we omit them here to conserve space. In Table 8, the diagonal elements of the matrix are common schools that do not change distance categories between 1900 and 1905. Boxes to the right of the diagonal summarise schools where a closer graded school opens. Table 9 portrays the same information for common schools open in both 1905 and 1910. To understand whether changing proximity mattered, we compare the figures on the diagonal to the figures right of the diagonal. Few schools are to the right of the diagonal, especially for the most remote 21 common schools. We see little discernible attendance pattern in the schools. Between 1900 and 1905, common schools that move from 3 to 10 kilometers from a graded school to less than 3 kilometers had relatively large attendance increases, but this was not repeated over 1905-1910. Average attendance rates fell slightly by 1910 among the 14 schools gaining a graded school within 5 kilometres. It is difficult with the data available to construct a clean counterfactual with which to assess the impact of expanding the graded school network on educational opportunities in other schools. Tables 8 and 9 suggest that grading schools probably had little impact on attendance outcomes in surrounding common schools. Conclusions North American educators stressed the importance of raising and maintaining primary school attendance rates in the late 19th and early 20th century. In British Columbia, attendance was sporadic well into the twentieth century, and school inspectors linked poor attendance to poor outcomes on high school entrance examinations. Our analysis of a panel of British Columbia’s public schools suggests that attendance rates responded strongly to the addition of a second teacher. Graded schools had about 10 percent higher attendance rates than common schools. The attendance impact of a second teacher far outweighs the impact of changes in class size, teacher qualifications, or teacher compensation. Our results also show that age grading and division of labour in monitoring appear to attract pupil attendance whether or not schools improved their physical infrastructure, and that the economies of scale in operating a graded school outweigh the attendance impact of increasing the availability of local alternative common (one-room) schools. Our findings suggest that allocating additional resources to the employment of a second teacher could have a substantial payoff through increased pupil attendance. Increasing attendance rates from 60 to 70 percent for a group of pupils who attend school from the age of 6 to 12 raises the amount of time the average pupil is actually in school by 22 about 5 months.33 If the return to a year of primary schooling was in the order of 4 percent (Goldin and Katz 1999), this implies that raising attendance rates raises future pupil earnings by about 1.7 percent. For a graded school with 2 teachers and 80 pupils, the net present value of a 1.7 percent permanent increase in pupils earnings is considerable when compared to the $60 to $100 monthly salary paid to the additional teacher. To return to the debate on school quality versus school access, our findings suggest that at least one dimension of school quality had a large impact on attendance in the early 20th century. Establishing new common schools did not have a comparable impact on attendance rates, but may have raised enrolment, especially in the remote hinterlands well away from major urban settlements. The total contribution of new hinterland schools to total enrolment, however, was small. New “remote” schools more than 10 kilometres from the nearest alternative school are always less than 10 percent of the total number of common schools, and throughout 1900 to 1920 they had on average fewer than 20 pupils enrolled within the first 5 years of opening. These schools may have had a large impact on opportunities in the most marginal areas of the province. Nevertheless, by 1910 most of the population was within walking distance of at least one school, while attendance rates remained highly variable. Hiring second teachers in common schools was a highly effective way to raise schooling attainment in early 20th century. 33 This calculation assumes a 9 month school year 23 References Burr, Nelson R. (1942) Education in New Jersey, 1630-1871. Princeton: Princeton University Press Card, David and Alan Krueger (1992) “School quality and black-white relative earnings: a direct assessment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(1), pp. 151-200. Chin, Aimee (2005) “Can redistributing teachers across schools raise educational attainment? Evidence from Operation Blackboard in India.” Journal of Development Economics 78, pp.384-405. Duflo, Ester, and Abhijit Banerjee (2005) “Adressing absence.” MIT mimeo. Duflo, Ester, and Rema Hanna (2006) “Getting teachers to come to school.” MIT mimeo. Elections British Columbia (1988), Electoral history of British Columbia, 1871-1986. Victoria: Queen’s Printer for British Columbia. Emery, Herb, and Clint Levitt (2002) Galenson, David G. (1995a) “Educational opportunity on the urban frontier: nativity, wealth, and school attendance in eadrly Chicago.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 43, pp. 551-563. Galenson, David G. (1995b) “Determinants of the school attendance of boys in early Chicago.” History of Education Quarterly 35(4), pp. 371-400. Goldin, Claudia (1998) “America’s graduation from high school: the evolution and spread of secondary schooling in the twentieth century.“ Journal of Economic History, 58(2), pp. 345374. Goldin, Claudia (2001) “The human capital century and American leadership: virtues of the past.” Journal of Economic History, 61(2), pp. 263-292. Goldin, Claudia, and Larry Katz (2000) Hanushek, Eric (1995) “Interpreting recent research on schooling in developing countries.” World Bank Research Observer, 10(2), pp. 227-246. Hanushek, Eric (1997) “Assessing the effects of school resources on student performance: an update.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 19(2), pp. 141-164. Hanushek, Eric, (2007) “School resources,” in Handbook on the Economics of Education, eds. E. Hanushek and F. Welch. Amsterdam: Elsevier. (Forthcoming) Harrigan, Patrick J, (1992) “The development of a corps of public school teachers in Canada, 1870-1980.” History of Education Quarterly, 4(winter), pp. 483-521. Johnson, F. Henry, (1964) A History of Public Education in British Columbia. Vancouver: 24 UBC Publications Centre. Kaestle, Carl F. and Maris A Vinovskis, (1980) Education and social change in nineteenthcentury Massachusetts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Katz, Michael B, (1968) The irony of early school reform: educational innovation in midnineteenth century Massachusetts. Cambridge (Mass): Harvard University Press. Katz, Michael B, and Ian E. Davey, (1978) “School attendance and early industrialization in a Canadian city: a multivariate analysis.” History of Education Quarterly 18(3): pp. 271-293. Kremer, Michael (2003) “Randomized evaluations of educational programs in developing countries: some lessons.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 93(2), pp. 102-106. Stephen Machin, Sandra McNally, and Costas Meghir, (2007) “Resources and standards in urban schools.” IZA discussion paper 2653. Margo, Robert (1986) “Educational achievement in segregated school systems: the effects of “Separate-but-Equal.” American Economic Review 76(4), pp. 794-801. Margo, Robert (1987) “Accounting for racial differences in school attendance in the American South, 1900: the role of Separate-but-Equal.” Review of Economics and Statistics 69(4), pp. 661-666. Moehling, Carolyn (2004) “Family structure, school attendance, and child labor in the American South in 1900 and 1910.” Explorations in Economic History 41(x) pp. xxx-xxx. MacKinnon, Mary, and Chris Minns (2006) “Canadian school attendance in 1910: laws, costs, and family characteristics.” Paper presented at 2006 CEA Joel Perlmann and Robert Margo (2001), Women’s work? American schoolteachers, 16501920. Chicago: U of Chicago Press. Pischke, Jorn-Steffen (2007), “The impact of the school year on student performance and earnings: evidence from the German short school years.” Economic Journal 117, pp. 12161242. Wilson, J. Donald, Robert M. Stamp, and Louis-Philippe Audet (1970) Canadian Education: a History. Scarborough (Ont): Prentice-Hall. 25 Table 1: Aggregate School Enrolment and Attendance Rates, 1901-1931 Canada PEI NS NB Quebec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta BC Census reports “at school” Census reports “at school 7-9 months” Enrolment as % of population aged 5-19 1901 1911 1921 1931 61.9 62.9 68.1 69.7 55.7 55.6 62.9 62.8 64.5 65.3 64.8 69.2 58.4 59.4 56.8 63.5 55.2 57.2 62.2 62.5 71.5 72.3 75.5 79.6 59.0 58.6 64.3 67.0 52.9 73.7 71.5 60.0 71.9 70.6 61.8 60.3 62.7 62.8 52.1 52.9 61.3 65.6 42.6 44.8 53.9 62.1 Attendance as % of Enrolment 1901 61.8 59.3 54.5 56.2 73.8 55.9 53.1 64.9 1911 64.0 60.4 59.5 62.1 77.5 58.9 56.3 53.0 52.8 65.8 1921 71.7 65.4 71.5 67.4 77.5 70.6 66.8 61.3 67.7 79.8 1931 79.6 72.7 75.7 79.8 83.0 77.3 78.6 76.7 80.9 87.2 Notes and sources: Attendance and Enrolment figures drawn from provincial records Enrolment estimates for 1901, 1911 and 1921 from Canada Year Book 1925, pp. 893-4 , and for 1931 from CYB, 1934-35, pp.1045-6. Estimates are for ordinary day schools, both public and private. Population, 1931 Census of Canada, Vol. 1, pp. 388-93. Answers to census questions about school attendance as reported in CYB 1925, p. 131 and 1934-35, p. 161. 26 Table 2: Public schools in British Columbia, 1900-1920 1900 1905 1910 1914 1920 # High schools 5 13 23 36 53 # Graded schools 58 86 132 243 292 # Common schools 264 290 388 492 612 % primary enrollment in Graded School 67 74 78 83 85 % electoral districts with High School 10 31 43 85 96 % of children at primary schools within 5 miles of any other primary school 77 79 89 90 91 % of children at primary schools within 5 miles of a high school 59 69 73 76 83 % of primary enrollment in lowest 2 reading books 37 32 33 29 26 % of primary enrollment in top readers 22 25 21 20 21 27 Table 3: Primary School Characteristics, BC 1900-1920 1900 1920 Graded Common Graded Common Mean # of divisions in school 4.9 (4) 1 (0) 6.3 (5.5) 1 (0) Mean Days in session 191 (29) 198 (34) 179 (18) 179 (19) % teachers with academic certificate 10 10 10 5 % teachers with first class certificate 37 14 24 12 % second class certificate 44 50 49 39 % male teachers 29 44 16 16 Mean School Enrollment 295 (247) 35 (22) 245 (233) 21 (10) % boys 48 45 51 51 Average class size 60 (17) 35 (22) 35 (7) 21 (10) Average monthly salary 56 (13) 51 (6) 113 (36) 86 (10) Monthly salary/student 1.1 (0.3) 2.1 (1.1) 3.0 (0.7) 5.2 (2.8) 66 58 83 74 % Attendance Standard deviation shown in parentheses 28 Table 4: British Columbia Public School Teachers, 1900 and 1920 % 1900-01 1920-21 Men Women Men Women academic 24 5 38 9 1st class 32 19 22 17 2nd class 32 55 15 47 3rd class 5 14 5 18 Other / unknown 7 7 20 9 6 1 26 4 Graded school 35 53 47 69 One-room (Common) school 59 47 15 24 11 15 24 19 6 11 9 7 administrator 22 3 37 6 previous employment as BC teacher 39 28 52 39 certificate: Taught in a: high school Taught in Vancouver Taught in Victoria married woman / widow 5 5 N 234 384 430 2,074 Notes: Special certificates included with “Other” – generally teachers of manual training or domestic science or physical drill. A few were teachers for handicapped children. Many of these teachers were at “special” schools, or were itinerant teachers – these schools and groupings not shown. Previous employment – taught in a BC school in 1895-6 for 1900-01 group, taught in a BC school in 1916-17 for 1920-21 group. 29 Table 5: Explaining attendance at British Columbia Schools, 1900 to 1920 (1) (2) (3) All schools Schools in Schools in op all years op all years Log average pay .058 (3.47) .086 (3.17) .129 (3.70) Class size*10 -.021 (-13.51) -.025 (-7.05) -.036 (-7.51) % boys -.054 (-2.67) -.058 (-1.50) -.047 (-0.92) Session days*100 -.057 (-6.08) -.078 (-3.33) -.092 (-3.44) Graded school .101 (13.56) .094 (7.93) .056 (3.20) Male teacher present .007 (1.25) .021 (2.25) .017 (1.53) Teacher with 2nd class or better certificate .001 (0.26) -.003 (-0.32) .001 (0.10) Distance to nearest high school > 5 kilometers -.019 (-2.67) -.028 (-2.18) -.007 (-0.41) Distance to nearest primary school > 5 kilometers -.022 (-3.91) -.015 (-1.52) -.022 (-1.21) No local post office .010 (1.68) -.028 (-2.25) -.030 (-1.43) Post office revenue>$1000 .041 (5.58) .012 (0.98) .034 (1.69) Post office revenue>$5000 .058 (2.10) .041 (1.00) .023 (0.52) Constant .608 (9.05) .537 (4.70) .384 (2.46) Year dummies Yes Yes Yes School dummies No No Yes N 2137 663 663 R2 .40 .46 .62 30 Table 6: Explaining attendance – including subject data (1) (2) (3) All schools Graded schools Common schools Log average pay .053 (3.07) .091 (3.49) .050 (2.34) Class size*10 -.028 (-12.07) -.029 (-6.78) -.028 (-10.11) % boys -.043 (-2.13) -.080 (-2.16) -.042 (-1.75) Session days*100 -.074 (-7.50) -.134 (-6.55) -.068 (-5.92) Graded school .100 (13.35) Male teacher present .002 (0.28) .009 (1.14) .002 (0.22) Teacher with 2nd class or better certificate -.0001 (-0.01) .013 (0.54) -.002 (-0.31) Distance to nearest high school > 5 kilometers -.019 (-2.55) -.024 (-3.08) -.015 (-1.41) Distance to nearest primary school > 5 kilometers -.020 (-3.42) -.017 (-1.68) -.019 (-2.77) No local post office .010 (1.70) .016 (1.25) .011 (1.50) Post office revenue>$1000 .044 (5.84) .030 (3.64) .051 (4.69) Post office revenue>$5000 .062 (2.03) .111 (3.59) -.022 (-0.36) % junior readers -.095 (-4.85) -.056 (-1.55) -.104 (-4.51) % senior readers .027 (1.19) -.040 (-0.93) .042 (1.55) Constant .678 (9.61) .718 (6.46) .674 (7.71) Year dummies Yes Yes Yes School dummies No No No N 2090 536 1554 R2 .41 .51 .30 31 Table 7: Transitions from One-Room to Graded Schools: Class size and Attendance 1905 1910 1. Common school in 1905, graded in 1910 (N=23) Attendance rate (%) 59 70 Average Class Size 44 (15) 38 (8) Postal revenue > 0 (%) 70 78 Av. postal revenue 813 (1593) 1519 (3041) Average # present 25 (8) 26 (5) 2. Common school in 1905, common in 1910 (N=178) Attendance rate (%) 61 61 Average Class Size 26 (11) 27 (13) Postal revenue > 0 (%) 82 82 Av. postal revenue 486 (1307) 856 (2727) Average # present 15 (6) 16 (7) 3. Common school in 1905, common in 1910, 1905 class size 30 or more (N=59) Attendance rate (%) 57 61 Average Class Size 38 (7) 37 (12) Postal revenue > 0 (%) 92 83 Av. postal revenue 955 (2119) 1645 (4443) Average # present 22 (5) 22 (7) 4. Graded school in 1905, graded in 1910 (N=59) Attendance rate (%) 69 73 Average Class Size 49 (10) 47 (12) Postal revenue > 0 (%) 98 97 Av. postal revenue 24282 (38297) 63335 (117368) Average # present 34 (8) 34 (8) 5. Graded school in 1905, graded in 1910, 3 classes or less (N=25) Attendance rate (%) 65 70 Average Class Size 43 (10) 43 (16) Postal revenue > 0 (%) 96 92 Av. postal revenue 4007 (12080) 6446 (20504) Average # present 28 (5) 29 (9) 32 Table 8: Attendace rates at common schools and distance to graded schools, 1900 and 1905 Distance to graded, 1905 Distance to graded, Over 20 1900 10 to 20 5 to 10 Over 20 10 to 20 5 to 10 3 to 5 .60 / .61 .57 / .63 .38 / .57 [49] [3] [3] .57 / .60 .56 / .63 .57 / .61 .70 / .73 [22] [10] [1] [3] Less than 3 .58 / .59 .61 / .57 .47 / .61 [41] [4] [3] .59 / .58 .55 / .66 [17] [5] 3 to 5 Less than 3 .56 / .57 [18] Notes: First number is attendance rate in 1900, second number is attendance rate in 1905. Number of observations are in square brackets. 33 Table 9: Attendace rates at common schools and distance to graded schools, 1905 and 1910 Distance to graded, 1910 Distance to graded, Over 20 1905 10 to 20 Over 20 10 to 20 5 to 10 .62 / .62 .59 / .61 .62 / .66 [47] [3] [6] .64 / .63 .57 / .63 .57 / .54 [26] [6] [1] 5 to 10 3 to 5 3 to 5 Less than 3 .61 / .62 .60 / .56 .57 / .59 [38] [11] [3] .61 / .62 [19] Less than 3 .57 / .58 [18] Notes: First number is attendance rate in 1905, second number is attendance rate in 1910. Number of observations are in square brackets. 34 35 36 37 38 Figure 5: schools adding second teachers - 1905 to 1910 0.90 60.0 attendance 0.80 50.0 0.70 40.0 class size att rate 0.60 0.50 class size 0.40 0.30 30.0 20.0 0.20 10.0 0.10 0.00 0.0 year - 4 year - 3 year - 2 year - 1 year N= 24 39 year + 1 year + 2 year + 3 year + 4