Alan Green, Mary MacKinnon and Chris Minns

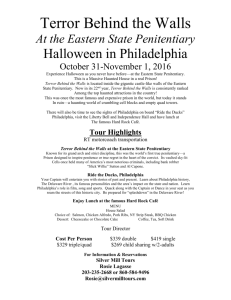

advertisement

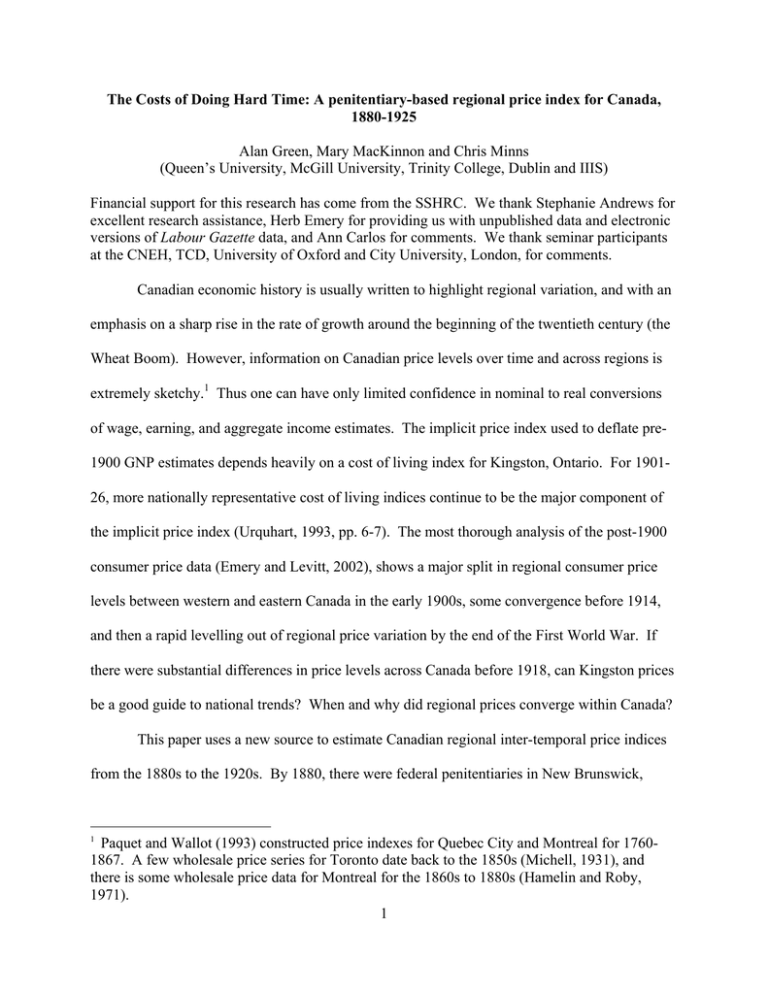

The Costs of Doing Hard Time: A penitentiary-based regional price index for Canada, 1880-1925 Alan Green, Mary MacKinnon and Chris Minns (Queen’s University, McGill University, Trinity College, Dublin and IIIS) Financial support for this research has come from the SSHRC. We thank Stephanie Andrews for excellent research assistance, Herb Emery for providing us with unpublished data and electronic versions of Labour Gazette data, and Ann Carlos for comments. We thank seminar participants at the CNEH, TCD, University of Oxford and City University, London, for comments. Canadian economic history is usually written to highlight regional variation, and with an emphasis on a sharp rise in the rate of growth around the beginning of the twentieth century (the Wheat Boom). However, information on Canadian price levels over time and across regions is extremely sketchy.1 Thus one can have only limited confidence in nominal to real conversions of wage, earning, and aggregate income estimates. The implicit price index used to deflate pre1900 GNP estimates depends heavily on a cost of living index for Kingston, Ontario. For 190126, more nationally representative cost of living indices continue to be the major component of the implicit price index (Urquhart, 1993, pp. 6-7). The most thorough analysis of the post-1900 consumer price data (Emery and Levitt, 2002), shows a major split in regional consumer price levels between western and eastern Canada in the early 1900s, some convergence before 1914, and then a rapid levelling out of regional price variation by the end of the First World War. If there were substantial differences in price levels across Canada before 1918, can Kingston prices be a good guide to national trends? When and why did regional prices converge within Canada? This paper uses a new source to estimate Canadian regional inter-temporal price indices from the 1880s to the 1920s. By 1880, there were federal penitentiaries in New Brunswick, Paquet and Wallot (1993) constructed price indexes for Quebec City and Montreal for 17601867. A few wholesale price series for Toronto date back to the 1850s (Michell, 1931), and there is some wholesale price data for Montreal for the 1860s to 1880s (Hamelin and Roby, 1971). 1 1 Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia, and starting in 1883, very detailed information on their expenditures was published. We address three questions: 1) How did east-west relative prices change over time? British Columbia was politically part of Canada in 1883, but the transcontinental rail link was completed only at the end of 1885. If the C.P.R. tied Canada together economically, then we might expect regional price gaps to drop sharply within a few years of the railway’s completion. However, the rapid settlement of the west during the Wheat Boom could have created substantial demand shocks that kept prices high. Price series extending from the 1880s to the 1920s allow comparisons over several phases of Canadian economic development. 2) Within eastern Canada, how similar were prices in areas that were long-settled and had well-established means of transportation by 1880? In line with Canadian historiography on regional variation, we find much bigger price differentials both within eastern Canada, and between eastern and western Canada, than appear in similar price indices for the northern United States. Most goods could not pass freely across the Canada US border, as there were substantial tariffs, and this would have allowed price differentials to persist. Canada had less welldeveloped retail and wholesale networks than the US at this time, which could have caused substantial regional price variation. 3) How different are estimates of aggregate growth when a new national price series is used instead of Urquhart’s deflator? We find three substantial differences. First, per capita real income grew faster from 1883 to 1899. Second, while growth was rapid from 1899 to 1913, it was a little slower than Urquhart estimated. Third, given that we estimate prices were more volatile from 1914-22, we find a substantial disruptive effect of the Great War. Overall growth 2 from 1883 to 1922 was somewhat higher than the Urquhart estimates indicate, suggesting a greater degree of convergence towards US income levels. Penitentiaries as a source of price data The principal sources for this price index are records of expenditures for Canadian federal penitentiaries, published as part of the Annual Report of the Auditor General (abbreviation AGR).2 The penitentiaries were in or fairly near major urban areas. In eastern Canada, penitentiaries were located in Dorchester (east of Moncton, New Brunswick, near the New Brunswick / Nova Scotia border, to the north-east of Saint John, the largest city in New Brunswick), north of Montreal (St Vincent de Paul), and Kingston (at the east end of Lake Ontario). In Western Canada, the British Columbia Penitentiary was in New Westminster, now a suburb of Vancouver, while the Manitoba Penitentiary was in Stony Mountain, about 15 miles north of Winnipeg.3 Two new federal penitentiaries were constructed on the prairies in the early 20th century. There was a penitentiary in Edmonton, Alberta, from 1906 to 1920 (why it closed in 1920, we aren’t sure). The Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert opened in 1911. In some years, the AGR also includes information for the Prince Albert and Regina jails, and we include information from these prisons whenever possible. When Saskatchewan became a province in 1905, these jails were transferred to provincial responsibility. Table 1A shows inmate numbers in each of the penitentiaries. Kingston was always the largest institution. While Kingston was a fairly small, and slow-growing, city (Table 1B), Ontario was the most populous province. Most prisoners in the Kingston Penitentiary came from Criminals sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 2 years or more serve their time in a federal penitentiary. Provincial sessional papers rarely include the necessary level of detail on expenditures by other prisons. 3 The British Columbia, Manitoba, and Dorchester Penitentiaries were all new buildings. The St. Vincent de Paul penitentiary was first a reformatory for boys. In the late 1860s, Kingston 2 3 Ontario. Part of the reason for using Kingston as the base for our price index is that such a large institution purchased most items every year. Inmate numbers in each penitentiary varied considerably over time, in part because total Canadian population expanded and shifted westwards. Business cycles also had an effect on inmate numbers, with the turn-of-the-century boom and the wartime boom reducing penitentiary populations in 1902 and 1917. The office of Auditor General was established in 1878, and the first Auditor General and his staff pursued their task vigorously (Sinclair, 1979). Correspondence with hapless civil servants who had failed to provide adequate information about expenditures, or whose departments had spent more than was authorized, was published as part of the report. It appears that penitentiary clerical staff submitted quickly and thoroughly to the firm demands of the Auditor General. The expenses include much information relevant to the cost of living outside the prisons. Prisoners and prison officers were fed and clothed, and prisons consumed coal and other fuels for heating and light. The penitentiary data have several advantages over other sources of cost of living information for the same period. The first is that the information is presented in a similar way from 1883 to 1922. Another is that the AGR prices are the actual prices paid by the prisons, and a third is that penitentiaries very likely purchased goods of the same (low) quality every year.4 The federal government’s Department of Labour published retail price data in The Labour Gazette (abbreviation LG) for 1900 onwards, but information is available monthly only from 1910. The Bertram and Percy (1979) and Emery and Levitt (2002) series start in 1900 Penitentiary held about 800 inmates, but Quebec inmates were transferred out by the mid-1870s. 4 The later AGR list the name and location of suppliers as well as prices and quantities. In many cases, an individual supplier sold the same good to several, if not all, of the penitentiaries, and it 4 because they rely on LG reports. Barnett (1963) ends his study of Kingston in 1900.5 Between 1910 and 1922, the LG data were drawn from reports by Gazette correspondents in Canadian cities. The correspondents were instructed to collect price information “from retailers doing considerable trade with working men.” We do not know how representative the retail prices reported by correspondents were, and whether the quality of data collection changed over time and place. The price quotations for 1900 and 1905 were collected retrospectively from the account books of retailers later surveyed by LG correspondents.6 Barnett uses a variety of sources, especially newspaper reports of prevailing market prices, as well as retailers’ account books. While our source has clear advantages, it is subject to important queries. Price patterns across the penitentiaries may not be representative of relative retail prices. Below, we address this question directly by comparing penitentiary prices for some important foods to Labour Gazette prices, and to scattered evidence on 19th century prices. We suggest that penitentiaries can be thought of as having been somewhat similar to retail establishments. While penitentiaries would have been relatively large purchasers of common items (such as flour and potatoes), many retail establishments in medium sized towns bought at least as much each year. Some of the luxury items were purchased by the prisons only at Christmas, or only for the staff, and so annual expenditure on these items was modest. Penitentiary populations generally rose between the 1880s and the 1920s, but so did the size of almost all towns, and very often the scale of businesses. is highly likely that these were identical items. 5 Allen (1994) relies on Barnett for pre-1900 trends, and on LG data for Toronto and Vancouver for 1900-1914. 6 These LG price quotations are for December. The penitentiary data usually include several price quotes for major goods. 5 Penitentiaries advertised for tenders for supplies (amounts spent were reported in the AGR), and complaints about the inefficiency of having each penitentiary order its own supplies appear in the Reports of the Inspector of Penitentiaries up to the 1920s (e.g. report for 1920-21, SP 35, p. 12). Can we think of the prisons’ purchasing patterns as being similar to what retail merchants in the same area would have been doing? There are at least three ways in which the penitentiary buying patterns were unusual. Most obviously, the penitentiaries bought a plain diet and cheap clothing, but spent heavily on providing large and solidly-built premises.7 Wardens and the Inspector presumably told each other about problems with particular suppliers, so that decision makers in British Columbia probably had more information about possible suppliers in Quebec and Ontario than did a typical retail merchant in B.C. Penitentiaries purchased some highly specialized items (locks, steel bars, prison cloth, etc.) that were quite possibly only made by one or two suppliers.8 Not only were the specific prison items unlikely to be purchased by retail merchants, a typical small-town general merchant probably did not stock any extremely specialized items, and may therefore have had less reason to turn to distant producers. Political influence could have affected the awarding of contracts. Our initial investigation of penitentiary supply patterns reveals little evidence that political affiliation was important. There was considerable turnover in the firms supplying the penitentiaries, and turnover was not closely associated with changes in the party in power in Ottawa. The office of the Auditor General was supposed to reduce the incidence of political patronage and other forms 7 Every penitentiary had a farm, and various workshops as well (Curtis et al. 1985). Where a penitentiary did not purchase an important food item, such as potatoes, pork, or milk, this was usually because its farm supplied the good. We have avoided using the prison farm prices listed, instead looking for other institutions purchasing the same item. 8 Goods purchased from the U.S. were virtually always of this type, for example guns or 6 of corruption. A firm that failed to secure a contract knew what its competitors were receiving because Sessional Papers were public documents. The rapid turnover of suppliers may reflect low profit margins on the business, low quality of goods supplied, or ease of entering the penitentiary supply business. There may have been considerable waste, supplies may have been pilfered by guards, and unauthorized expenditures may have been disguised as legitimate purchases. None of these, however, would have affected the accuracy of the prices listed.9 Constructing a price index for Canada, 1883-1922 We have selected twelve years of the AGR around which to build our penitentiary price index: 1883/84, 1886/7, 1889/90, 1892/93, 1895/96, 1899/1900, 1905/06, 1910/11, 1913/14, 1917/18, 1919/20, and 1922/23. Up to 1906, reports are for the twelve months ending June 30th . Beginning in 1907, the fiscal year ends March 31st.10 The 1883/4 report is the first listing detailed expenditures for individual goods, and 1886/7 is the first year after the completion of the CPR main line. The 1889/90, 1899/1900, and 1910/11 reports include price information relevant for the census of 1891, 1901, and 1911. The Wheat Boom is conventionally dated as having begun c. 1896, and 1913/14 was the last peacetime year. The 1917/18 and 1919/20 Reports give an indication of the intensity of war and post-war inflation, and the 1922/3 report is the last listing the prices for individual goods acquired in purchases of $500 or less.11 A price index represents the relative cost of consumer expenditures over time or across machinery used in large buildings or in the workshops. 9 The reports of the Inspector of Penitentiaries usually include the per capita costs of maintaining prisoners in each institution, and Wardens of the higher cost institutions were clearly under pressure to reduce, or at least justify, their expenditures. 10 Reports were published in the next series of Sessional Papers. Therefore, the 1899/1900 AGR is in 1901 Sessional Papers. 11 In principle, we could construct an index for every year from 1883/4 to 1922/3, but in the early years we are sometimes forced to use price quotations from an adjacent year, so that up to the mid-1890s we could at most generate numbers for every other year. 7 regions. A set of weights is needed to aggregate expenditures over a range of goods. We follow the existing literature in constructing indices with relative quantities of goods fixed across time.12 Emery and Levitt's (2002) index uses weights adopted by Bertram and Percy (1979). For food items, their weights are derived from the 1901 United States expenditure survey, while weights for fuel and light are based on 1926 Dominion Bureau of Statistics estimates of domestic national consumption. Bob Allen's (1994) comparison of the cost of living in British emigrant destinations, including Canada, used weights based on British working-class household expenditure. We mainly employ the weights Haines (1989) used in his regional price index for the United States in 1890. Haines' index is based on data collected as part of the Aldrich Report in 1889 and 1890. This report included budgets for over 2000 families, from which expenditure weights can be derived. We find Haines' weighting system attractive for two reasons. First, we expect that a representative budget for late 19th century American families would be similar to the budget of the typical Canadian family. These weights are fairly close to those used by Bertram and Percy (1979) and Emery and Levitt (2002). The second reason we adopt Haines' weights is that he provides weights for commodity subgroups as well as individual goods. The price index for food is divided into cereal and bakery products, meat, fish and fowl, dairy, vegetables, fruit, condiments, and other foods. This structure is useful as we often have price observations for several, but not all, of the goods within a subcategory. Where a penitentiary purchase price was absent, whenever possible we used prices in federal or provincial reports for 12 As Haines notes (1989, p. 100), an index with fixed quantity weights is not a “true” cost of living index, as substitution effects in response to spatial (and temporal) variation in relative prices are ignored. We follow Allen (2001) in constructing a geometric price index as an alternative. The results, available in the full version of this paper, are little different when we adopt this approach. 8 other nearby institutions, or for years of little price change, the penitentiary price from an adjacent year.13 When no price could be found, we maintain the sub-category weights derived from the Aldrich report while re-weighting the contribution of the individual goods that make up the sub-category. Table 2 lists the four expenditure groups in our index: food, clothing, fuel and light, and “other” goods. Within the food sub-categories, flour, beef, potatoes, and butter receive high weights, as in the average budget in the Aldrich Report.14 The other goods within each subcategory receive equal weight. Unlike Haines, we cannot include alcohol and furniture, as there are few annually repeated prices for these goods in the penitentiary records. A potentially more serious omission is rent. Indicators of rental costs are few and far between in the reports of the penitentiaries. US budget studies, and the only Canadian source on late 19th century expenditure patterns, suggest that workers spent less than 20% of their income on rent (Dick, 1986, p. 480).15 For the clothing sub-index, we did not use Haines' sub-category weights. Prior to 1910, the penitentiaries purchased little ready-made clothing, but made large expenditures on various types of cloth and leather. We chose items for which we can find purchases by most penitentiaries in most years, and assign equal weight to each. Unfortunately, cloth prices are not reported for 1883/4, so this year’s index is based solely on the other three sub-indexes. The fuel and light sub-index consists of coal, wood, and coal oil, with the items weighted 13 For example, prior to 1891, Kingston Penitentiary milled its own flour (we find prices for wheat), so we use flour prices from the nearby insane asylum. Military records, records of Indian Schools, the North West Mounted Police, and of steamers operated by the Department of Fisheries, all provided some missing prices. 14 Bread dominates Haines' cereal and bakery product index, but with few exceptions the penitentiaries baked their own bread. We substitute flour for bread in our index. 15 Bertram and Percy (1979) and Emery and Levitt (2002), however, assign higher weights for rental costs in their indices. 9 according to Haines (1989).16 The final category contains two items that do not fit elsewhere: tobacco and soap.17 Their relative weights within the “other” sub-index again reflect Haines' work with the Aldrich report. Results Figure 1 and Table 3 present inter-temporal, inter-regional indices. We use Kingston in 1899 as the base city. In the mid-1880s, prices in Winnipeg and Vancouver were far higher than in the east, while Montreal prices were about 25 percent higher than Ontario or Maritime prices. By 1890, Winnipeg prices had fallen close to the level of Montreal prices, but Vancouver prices remained substantially higher than those found anywhere in eastern Canada. Prices in the western Prairies were closer to those of BC than Manitoba. In the early 1890s, price differentials across Canada were very much larger than those found at the same time in US cities near the Canadian border. According to Haines (1989, p. 101), 1890 prices in Portland (Oregon) were only 10-25% higher than prices in Bangor (Maine), Syracuse (New York), Minneapolis (Minnesota) or Detroit (Michigan). Prices in Chicago and Boston (excluding rents) were generally somewhat above those of the smaller cities.18 Why price variation within Canada was so much greater we are not yet sure. By the early 1900s we see further evidence of price convergence. Montreal prices are now well in line with those in Kingston and Dorchester. West of Winnipeg, there are still some years when prices far exceed eastern levels, but the regional price differentials are lower, sometimes substantially lower, than in the years before the turn of the century. By 1917/18, 16 The penitentiaries had electric light by about 1910, but some price quotations for coal oil continue to be given. 17 It may be possible to add a few hardware items, such as turpentine, nails, and lumber . 18 With Syracuse at 100, relative prices were Portland 121, Boston 113, Bangor 110, Chicago 108, Minneapolis 99, Detroit 98. 10 differences in the cost of living across Canada appear to be very small. We have the largest number of observations for the components of the food price index (Table 4A), and here it appears that the Western price premium always previously in evidence has been completely eliminated. While the turmoil associated with postwar inflation brought back a gap in the overall index for Vancouver, this seems to have been a short-term relapse. By the early 1920s, living costs in the highest price region were less than 10% above those in the lowest price region. Part of the reason for the reduction in the east-west gap is the sharp drop in the difference in the cost of fuel and light during the First World War. Coal output in Alberta increased rapidly after 1910, and this may have been partly responsible for the relative decline in western fuel prices.19 For the early 1900s, we have another way of comparing costs across penitentiaries: the average annual cost of feeding prisoners. The reports on penitentiaries gave total annual expenditures on rations, average daily number of prisoners, and for these years, the total value of prison farm produce consumed in the prison. Thus expenditure on rations plus farm produce consumed in the prison, divided by the average number of inmates, approximates food costs. Not all the food was consumed the same year, some was wasted, and some was eaten by the staff.20 We also remain unsure about the meaning of the prices assigned for produce grown on the farms – these may not always have been prevailing market prices.21 Prisoners’ diets were much less varied than the diet of Table 2. Well over half the total The price per ton of coal produced in western Canada rose more slowly between 1914 and 1920 than did the price of coal produced in eastern Canada. Canadian Mineral Statistics 18861956, pp. 56, 101,104,110. 20 We have not included expenditures on hospital luxuries like eggs, or on the staff mess. 21 The St. Vincent de Paul farm always produced the highest value of food consumed in the institution, probably because they raised a lot of pigs. The value of farm produce consumed in each prison changed substantially from year to year. 11 19 expenditure on rations was for beef and flour. Both goods were relatively transportable, so we expect to find smaller regional variation in provisioning prisoners than in feeding workers and their families. By 1908, inmate food costs were no higher in BC than in Kingston (about $45 per head). Prisons likely varied their diets according to the local cost of food, with BC buying more fish than Kingston, for example. We doubt that any free citizen would have volunteered to consume a prison diet, and individual consumers were not likely to buy beef and flour by the barrel. However, with many labourers earning only about $300 per year, the low cost of a prison diet gives some clue as to how poor working class families could have survived. Around 1910, the un-weighted national average cost of the LG’s food budget for a family of five was about $360 per year. Table 3 and Figure 1 show the cost of the consumption bundle falling sharply across Canada in the late nineteenth century, with Winnipeg seeing the largest drop in relative prices. In the first decade of the twentieth century, prices rose by about 35 percent in the three eastern cities. Winnipeg clearly continued on the path of price convergence with eastern Canada, with the overall price level increasing by only about 20 percent. The second decade of the twentieth century saw rapidly rising prices during and just after the First World War. By the time the war induced cycle of inflation and deflation was over, price levels in the east were only 30-40% above their immediate prewar levels, and at most 30% higher in the west. The east/west split that had been so obvious up to about 1910 had largely disappeared. Comparisons with other information about Canadian prices For most of the years covered by both our new indices and the Emery and Levitt (2002) indices, the cost of living patterns are roughly consistent, assuming that we can match prison prices with LG reports for Saint John, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Regina, Edmonton, and 12 Vancouver. Using either set of data, inter-urban price differentials fell markedly in the second decade of the twentieth century, and prices in the early 1920s were close to twice as high as they had been around 1900. We have no information on rents, while the Emery and Levitt series cannot include clothing. Therefore panels A and B of Table 4 show the food-only component of penitentiary and Emery-Levitt price indices, with Kingston in 1899/1900 and Toronto in December 1900 set to 100. Penitentiary data suggest even higher Vancouver prices than do LG records. Edmonton, Regina and Prince Albert prices were also often higher. However, our Saskatchewan data come from three different prisons, and the numbers of inmates in these 4 prisons changed rapidly (Table 1A), so we hesitate to put too much emphasis on results for Alberta and Saskatchewan. Both panels 4A and B show Ontario as the low-price province before the First World War, not just relative to western Canada, but also relative to Quebec and the Maritimes. Manitoba prices were not dramatically above Quebec and Maritime prices in most years before the war, while from Saskatchewan to British Columbia, prices were much higher than in Ontario. By the early 1920s, regional differentials had been largely ironed out. The one period where our indices diverge substantially from the Emery-Levitt and Bertram and Percy series, is around the end of the First World War. Part of the reason for this is different weightings – the Haines weights put more emphasis on goods that experienced the biggest price increases at this time, and also more weight on goods that were generally particularly expensive in Vancouver.22 Another reason for differences between penitentiary and LG based series would be For all penitentiaries, using the Emery-Levitt weights, but penitentiary prices, for the food items in both indices reduces food costs in 1922 by 10% or more. The Vancouver food price level is lowered in 10 of 12 years, but only in 1883 and 1922 is the reduction greater than 15%. 13 22 dissimilar trends in retail/wholesale markups, or in the prices of prison goods and higher quality items purchased by reasonably prosperous consumers. We compared LG prices for 1900-22 to penitentiary prices for four important foodstuffs: beef, flour, butter, and potatoes.23 With the exception of potatoes, the yearly average penitentiary price was never higher than the December retail price. This likely reflects both a quality difference and a retail markup. The ratios of potato prices bounce around considerably over time and place, probably reflecting seasonality in potato prices and the lack of transportability of potatoes. We see no clear pattern of penitentiary to retail price differentials across cities or over time. Thus we do not think it is likely that the degree of competition in retail markets changed systematically over time or place. During the war, all armies were purchasing huge volumes of the low quality foods that made up the bulk of penitentiary food purchases. However, for beef, flour, and butter, 1917/18 and 1919/20 ratios of penitentiary prices to December retail prices are generally similar to those of 1913/14. We need to explore this issue further: it is possible that with wartime scarcities of some consumer goods, LG correspondents were changing the grades of the items they reported on. In 1919 and early 1920, retail prices rose steadily. The Bertram-Percy and Emery-Levitt series rely on December LG prices. The average weekly cost of the LG family budget of food, fuel and light, and rent was 68% above the 1913 (annual) average in December 1919, 78% higher as of March 1920, and 92% higher in July 1920. Several of the goods the penitentiaries bought were purchased on contract. Presumably by 1917, and even more so by 1919, contracts had inflationary expectations built in. The penitentiary price series for these years anticipate retail price increases that occurred a few months later (Table 4, Panel C, column (3)). 23 We thank Herb Emery for supplying us with an electronic version of the Labour Gazette data. 14 We undertook the present project largely because of the scarcity of price data before 1900. Thus it is hard to verify pre-1900 penitentiary prices by comparing them with other price data. Our indices suggest a quite different picture from that drawn by Barnett for Kingston (Table 4, Panel C, column (4)). We see a larger decline from 1883 to 1900 in all three eastern penitentiaries, and the decline is spread through the 1880s and into the 1890s. The penitentiary price series for Kingston appears to move rather more like the Toronto wholesale price index for grains and flour (column (5)). There is support for our finding that prison prices were much lower in Kingston than in Montreal in the 1880s and 1890s. Federal government immigration agents occasionally reported retail prices in their district. In 1889 (SP 1890, vol. 6), Kingston prices for a range of food items, plus soap, tobacco, and wood, were 20-35% below Montreal prices. Implications of the new price series So far, wherever we have been able to check the penitentiary price series against other sources, the penitentiary prices are representative of prices in the broader community. If we could add a rent component to our index, we certainly would. Here, we investigate how much estimates of real GNP per capita change if we use a penitentiary price index, rather than the existing implicit price deflator (Table 4, panel C, column (1)). We show the impact of using six variations of the penitentiary price index (Table 5, columns (2) to (7)), and focus on the last. Each of the first five variations assigns different weights to the five original penitentiaries, based on regional population distributions (the Maritimes, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies, and British Columbia). All show substantially greater growth in income per capita between 1883 and 1922 than does the Urquhart series (column (1)). Column (7) is a simple average of the existing Urquhart series and the fifth variation. We assume that if we could control for other aspects of 15 expenditure, the trends in the penitentiary series would be somewhat reduced, and column (7) does this. Two sets of our new estimates, Urquhart’s series, and estimates of US GDP per head (in US 1899$) are shown in Figure 2. Are the real GNP per capita estimates of column (7) more in line than the estimates of column (1) with what we might expect, given our knowledge of Canadian economic development? We know that Canada lost a huge number of people to the republic to the south in the late 19th century. The new series suggest that the population exodus occurred at the same time as income per head for the remaining population was rising. This observation is consistent with evidence for the same period that high emigration rates from Ireland raised incomes in Ireland (Boyer, Hatton, and O’Rourke, 1994). The Wheat Boom (1896-1913) still appears as a major upturn in the rate of income growth. Our estimates suggest that most of the income growth per person was concentrated in the early part of the Wheat Boom. Slower growth coincided with the years of large scale immigration in the decade to 1914. The First World War was a tremendous shock to Canada. Over 650,000 men served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Morton, 1993, p. 278) at some time during the war, about a third of the male population of military age (15-44 in 1911). Our estimates suggest that growth stopped during the war, and that in the year of peak industrial unrest (1919), incomes were well below pre-war levels. The Urquhart series also shows a sharp drop in income by 1919, but a more moderate decline relative to 1913.24 By 1922/3, our new estimates show the short but very sharp downturn of 1921 was largely over. We think it plausible that by then incomes would have returned to roughly the prewar level. In 1920 and 1921, it cost about $1.12 Canadian to purchase $1 US, well away from the normal $1CDN=$1US exchange rate (HSC series H627). This seems in line with our impression that there was more inflation in Canada than the US around this time. 16 24 Conclusions For the years where both LG and penitentiary data are available, we mainly get similar results. We therefore feel more confident about the likely reliability of both for the periods when only one is available (after 1922 and before 1900). Why series based on the December LG data show so much less inflation around end of the First World War, we are not sure. The findings based on the new price index are 1) Price dispersion across the country was much higher in the early 1880s than in 1900. The completion of the transcontinental railway presumably lowered prices in Winnipeg. Vancouver prices initially diverged from those in the rest of the country, and remained much higher into the early 1900s. In eastern Canada, where rail and water links were long established, Montreal prices were higher than those of southern Ontario or New Brunswick until the late 1890s, but then dropped sharply. Around 1890, regional price differences in Canada were substantially greater than in northern regions of the U.S. 2) The 1880s and 1890s in Canada, as in other trading countries, were generally years of declining prices. Our data suggest that prices fell substantially more in this period than has been previously thought. After 1900, prices rose in all parts of the country, but at quite unequal rates by region. By 1913, living costs as far west as Winnipeg were fairly well standardized, and by the early 1920s, price levels were similar across the country. 3) The time path of economic growth per capita is substantially altered by using the penitentiary price index rather than the existing implicit price index. Principally, we find greater growth before and at the beginning of the Wheat Boom, and a greater negative shock to the Canadian economy associated with the Great War and its immediate aftermath. 17 References Allen, Robert C. (1994), “Real incomes in the English speaking world, 1879-1913,” in Labour Market Evolution: the economic history of market integration, wage flexibility and the employment relation, eds. G. Grantham and M. MacKinnon. London: Routledge. Allen, Robert C. (2001), "The great divergence in European wages and prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War." Explorations in Economic History, 38 (4), 411-447. Balke, Nathan S. and Robert J. Gordon (1989), “The Estimation of Prewar Gross National Product: Methodology and New Evidence.” Journal of Political Economy, 97 (1), 38-92. Barnett, Robert Francis John (1963), “A Study of Price Movements and the Cost of Living in Kingston, Ontario for the Years 1865 to 1900.” Unpublished M.A. thesis, Queen’s University. Bertram, Gordon, and Michael B. Percy (1979), “Real wage trends in Canada 1900-1926: some provisional estimates.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 12 (2), 299-312. Boyer, George R., Hatton, Timothy J., and Kevin O’Rourke (1994), “The Impact of Emigration on Real Wages in Ireland, 1850-1914.” Eds. Timothy J. Hatton and Jeffrey G. Williamson. Migration and the International Labor Market. New York: Routledge, 221-239. Canada, Department of Labour. Labour Gazette. Ottawa: King’s Printer. Canada, Dominion Bureau of Statistics (1957), Canadian Mineral Statistics 1886-1956. Ottawa: Queen’s Printer. Curtis, Dennis, Graham, Andrew, Kelly, Lou, and Anthony Patterson (1985), Kingston Penitentiary: The First Hundred and Fifty Years, 1835-1985. Ottawa: The Correctional Service of Canada. Dick, Trevor J.O. (1986), “Consumer Behavior in the Nineteenth Century and Ontario Workers, 1885-1889.” Journal of Economic History, 46 (2), 477-488. Emery, J.C. Herbert, and Clint Levitt (2002), “Cost of living, real wages, and real incomes in thirteen Canadian cities, 1900-1950.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 35(1), 115-137. Haines, Michael R. (1989), “A state and local consumer price index for the United States in 1890.” Historical Methods, 22(3), 97-105. Hamelin, Jean, and Yves Roby (1971), Histoire Économique du Québec 1851-1896. Montreal: Fides. Johnston, Louis, and Samuel H. Williamson, "The Annual Real and Nominal GDP for the United States, 1789 - Present." Economic History Services, March 2004, http://www.eh.net/hmit/gdp/ Morton, Desmond (1993), When Your Number’s Up: The Canadian Soldier in the First World War. Toronto: Random House. Paquet, Gilles, and Jean-Pierre Wallot (1993), “Some Price Indexes for Quebec and Montreal (1760-1913).” Histoire Sociale/Social History, 31 (Nov.), 281-320. Scott, Jack David (1984), Four Walls in the West: The Story of the British Columbia Penitentiary. New Westminster: Retired Federal Prison Officers’ Association of British Columbia. Sinclair, Sonja (1979), Cordial But Not Cosy: A History of the Office of the Auditor General. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. Taylor, K.W. and H. Michell (1931), Statistical Contributions to Canadian Economic History, vol. II. Toronto: MacMillan. Urquhart, M.C. (1993), Gross National Product, Canada, 1870-1926: The Derivation of the Estimates. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 18 Table 1: Canadian Penitentiaries and Urban Populations, 1881-1923 A) Inmate Numbers Year Dorchester, St. Vincent Kingston Manitoba Regina Prince Alberta B.C. Total N.B. de Paul Jail Albert 1883 125 308 534 96 74 1,137 1886 149 278 578 90 105 1,200 1889 161 322 554 66 91 1,194 1892 172 374 532 75 17 75 1,245 1896 192 383 605 80 29 101 1,390 1899 226 447 570 112 21 5 90 1,466 1902 210 345 460 105 22 9 94 1,236 1905 233 357 448 190 31 21 139 1,398 1909 246 510 570 144 91 204 1,765 1913 195 405 516 200 95 206 351 1,958 1917 211 428 475 92 99 160 229 1,694 1920 306 520 615 156 186 34 197 1,931 1923 363 625 729 218 335 216 2,486 Source: Department of Justice, Report on Penitentiaries. Counts for one day – end of June to 1905, end of March thereafter. Prince Albert and Regina jails became the responsibility of Saskatchewan after 1905. 1913 on Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert. B) Urban Population (in ,000) Prince New City Moncton Montreal Kingston Winnipeg Regina Albert Edmonton Westminster Vancouver Province New Quebec Ontario Manitoba Sask. Sask. Alberta British British Brunswick Columbia Columbia 1881 5 155 14 8 2 1891 9 220 19 26 7 14 1901 9 328 18 42 2 2 4 6 27 1911 11 491 19 136 30 6 31 13 100 1921 17 649 22 179 34 8 59 14 117 Source: 1921 Census of Canada, Vol. 1, Table 12. Population totals appear to be for city boundaries as of 1921. Populations below 1,000 not shown in the source table. 19 Table 2: Expenditure weights for the penitentiary price index Fuel and Food Clothes Light 58 21 9 Cereals and Bakery 16 Fruit 4 Braces 7.7 Coal 42 Currants and Fuel Flour 10.7 raisins 2 Cotton 7.7 Wood 42 Prunes Coal Oil Barley 1.7 2 Canvas 7.7 16 Condiments 1 Hats, Straw Oatmeal 1.7 7.7 Pepper Rice 1.7 0.3 Leather, pebble 7.7 Meat, Fish, Poultry 33 Vinegar 0.3 Leather, split 7.7 Beef 18.8 Salt 0.3 Leather, sole 7.7 Fish (not herring) Other foods Leather, upper 20 4.7 7.7 Mutton Coffee Other 4.7 3.3 Linen 7.7 12 Bacon or Pork Eggs 4.7 3.3 Lining 7.7 Tobacco 43 Dairy Lard Soap 3.3 Serge 18 7.7 57 Butter 11.5 Molasses 3.3 Ticking 7.7 Milk Sugar 6.5 3.3 Tweed 7.7 Vegetables 3.3 9 Tea Beans 1.8 Potatoes 5.4 Peas 1.8 Weights of sub-components (bold), and weights of components (bold italics) sum to 100. 20 Table 3 Inter-temporal penitentiary price indices (Kingston 1899/1900=100) Regina/ St. Vincent Prince British Dorchester de Paul Kingston Manitoba Albert Edmonton Columbia 1883/1884 140 175 140 224 176 1886/1887 126 161 135 169 197 1889/1890 125 149 128 157 204 1892/1893 127 156 121 144 176 180 1895/1896 117 134 101 143 148 157 1899/1900 105 105 100 129 154 135 1905/1906 140 135 127 159 182 161 180 1910/1911 145 142 134 162 157 174 1913/1914 164 187 161 169 221 192 184 1917/1918 271 276 263 260 253 274 255 1919/1920 346 336 320 294 346 326 406 1922/1923 233 226 218 218 220 238 Table 4 – Inter-temporal price indices, food only A) Penitentiaries (Kingston 1899/1900 = 100) Regina/ Prince Dorchester Montreal Kingston Winnipeg Albert Edmonton Vancouver 1883/1884 150 176 141 226 178 1886/1887 118 142 127 156 178 1889/1890 129 153 132 162 190 1892/1893 125 148 120 134 166 179 1895/1896 126 126 99 132 143 159 1899/1900 111 108 100 121 146 140 1905/1906 139 133 122 156 156 175 175 1910/1911 142 147 141 152 159 186 1913/1914 171 171 153 194 221 185 188 1917/1918 299 285 279 262 271 273 287 1919/1920 345 319 322 290 345 312 380 1922/1923 208 204 189 197 166 229 B) Retail Prices, Emery-Levitt (Toronto, December, 1900 = 100) Saint John Montreal Toronto Winnipeg Regina Edmonton Vancouver 1900 114 117 100 117 138 107 122 1905 134 130 110 118 139 123 132 1910 155 134 128 141 158 142 161 1913 172 148 141 151 168 161 156 1917 249 242 244 224 251 221 235 1919 285 255 265 293 287 270 289 1922 207 192 192 187 196 189 203 21 C) Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century Price Indices (1900=100) CANADA KINGSTON Implicit Bertram Price and Percy, LG Barnett, Grains Index with Family Cost of and clothing Budget Living Flour Year (Urquhart) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) 1880 104 110 151 1883 112 125 148 1886 100 107 111 1889 106 109 126 1892 104 107 116 1895 91 91 111 1898 98 103 112 1900 100 100 100 100 100 1903 106 110 1906 111 123 1909 121 153 1912 131 132 147 160 1914 133 130 151 152 1915 137 136 146 181 1916 149 160 154 191 1917 176 190 196 302 1918 199 207 220 333 1919 219 225 235 299 1920 254 249 287 355 1921 226 209 230 217 1922 205 199 221 178 1923 208 201 220 163 TORONTO Animals Dairy and meats Products (6) (7) 101 107 123 117 93 100 99 101 97 95 87 85 87 84 100 100 106 101 118 114 128 130 140 149 158 152 156 167 191 194 264 241 317 266 325 315 303 336 209 270 199 227 187 242 US Imported Foods (8) 129 115 103 125 105 89 95 100 94 94 98 121 114 131 155 181 214 239 278 167 152 164 Implicit GNP deflator (9) 115 113 105 107 103 96 96 100 105 109 112 119 122 124 136 162 191 218 251 219 203 209 Sources: (1) Urquhart (1993, pp. 24-5); (2) Bertram and Percy (1979, p. 306); (3) LG (1921, p. 1057, 1923, p. 842, July prices 1914 on); (4) Barnett (1963, p. 8); (5-8)Taylor and Michell (1931, p.56) (9);Balke and Gordon (1989, pp. 84-5). 22 Table 5: The Effect of Changing Deflators on Estimated Canadian Income per Head, 1883-1922 (in 1899 $) Year 1883 1886 1889 1892 1895 1899 1905 1910 1913 1917 1919 1922 Urquhart, Kingston in 1899 $ Pen only (1) (2) 118 98 117 90 126 108 132 118 133 124 157 157 199 178 239 227 249 216 270 188 231 164 222 217 5 pens, weighted according to 1901 pop distrib (3) 92 88 106 111 112 157 176 227 215 196 169 224 5 pens, weighted according to 1921 pop distrib (4) 89 89 106 113 112 157 177 230 224 205 178 234 5 pens, weighted according to 1881 shifting pop population distrib weights (5) (6) 93 93 89 89 106 106 110 110 112 112 157 157 176 176 225 227 212 224 191 205 165 178 219 234 “Halfway” (Average of cols. (1) and (6)) (7) 106 103 116 121 123 157 188 233 237 238 205 228 US Real GDP per capita (US 1899 $) (8) 198 196 203 210 214 240 290 285 307 320 330 317 Sources and notes: Col. 1 from Urquhart (1993, pp 24-5); col. (2) using Kingston Penitentiary series as deflator; col. (3) using 5 penitentiaries, weighted by regional distribution of Canadian population in 1901; col. (4) weighting by regional distribution of Canadian population in 1921; col. (5) weighting by regional distribution in 1881; col. (6) weighting by 1881 population for 18831892, by 1901 population for 1895 to 1910, and by 1921 population distribution for 1913 to 1922; col. (7) is simple average of col. (1) and col. (6); Col (8) from Johnston and Williamson (2004). 23 75 150 225 300 375 Figure 2: Canadian and US income per capita, 1883-1922, 1899$ 1883 1886 1889 1892 1895 1899 year United States Kingston Pen 1905 1910 1913 19171919 1922 Urquhart Halfway Note: US Income in US 1899$, Canadian Income in Canadian $1899 24 index 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 Figure 1: Price levels, 1883-1923 (Kingston 1899=100) 1883 1886 1889 1892 1895 1899 year Dorchester Kingston Regina/PA Vancouver 25 1905 1910 1913 Montreal Winnipeg Edmonton 19171919 1922