275

advertisement

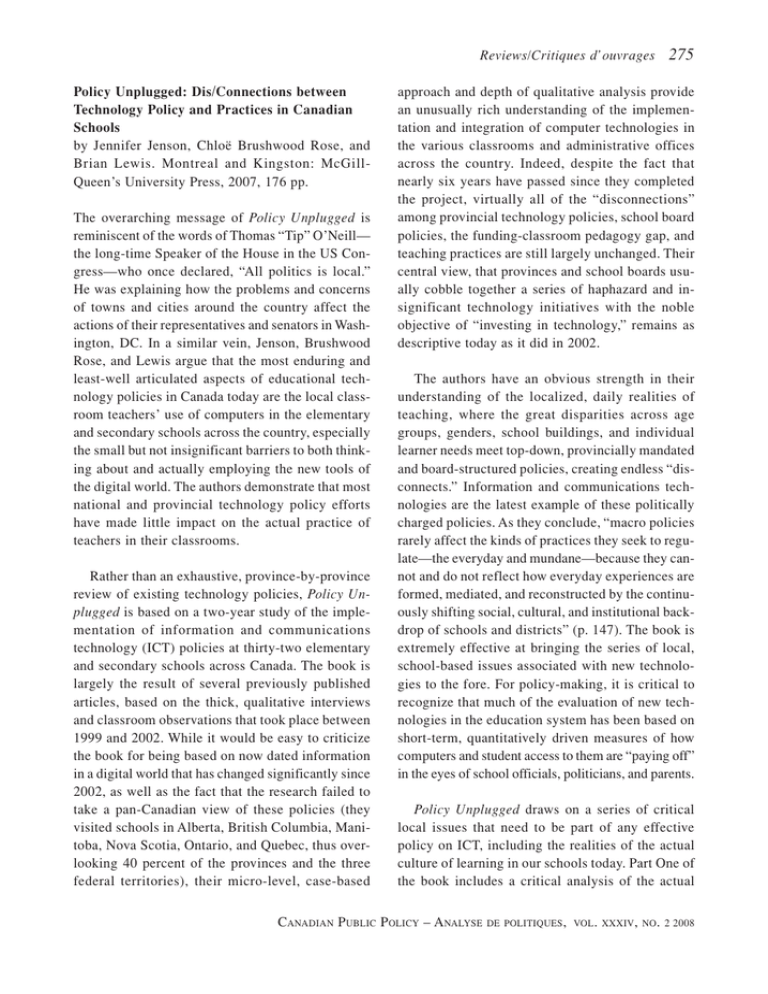

Reviews/Critiques d’ouvrages Policy Unplugged: Dis/Connections between Technology Policy and Practices in Canadian Schools by Jennifer Jenson, Chloë Brushwood Rose, and Brian Lewis. Montreal and Kingston: McGillQueen’s University Press, 2007, 176 pp. The overarching message of Policy Unplugged is reminiscent of the words of Thomas “Tip” O’Neill— the long-time Speaker of the House in the US Congress—who once declared, “All politics is local.” He was explaining how the problems and concerns of towns and cities around the country affect the actions of their representatives and senators in Washington, DC. In a similar vein, Jenson, Brushwood Rose, and Lewis argue that the most enduring and least-well articulated aspects of educational technology policies in Canada today are the local classroom teachers’ use of computers in the elementary and secondary schools across the country, especially the small but not insignificant barriers to both thinking about and actually employing the new tools of the digital world. The authors demonstrate that most national and provincial technology policy efforts have made little impact on the actual practice of teachers in their classrooms. Rather than an exhaustive, province-by-province review of existing technology policies, Policy Unplugged is based on a two-year study of the implementation of information and communications technology (ICT) policies at thirty-two elementary and secondary schools across Canada. The book is largely the result of several previously published articles, based on the thick, qualitative interviews and classroom observations that took place between 1999 and 2002. While it would be easy to criticize the book for being based on now dated information in a digital world that has changed significantly since 2002, as well as the fact that the research failed to take a pan-Canadian view of these policies (they visited schools in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec, thus overlooking 40 percent of the provinces and the three federal territories), their micro-level, case-based 275 approach and depth of qualitative analysis provide an unusually rich understanding of the implementation and integration of computer technologies in the various classrooms and administrative offices across the country. Indeed, despite the fact that nearly six years have passed since they completed the project, virtually all of the “disconnections” among provincial technology policies, school board policies, the funding-classroom pedagogy gap, and teaching practices are still largely unchanged. Their central view, that provinces and school boards usually cobble together a series of haphazard and insignificant technology initiatives with the noble objective of “investing in technology,” remains as descriptive today as it did in 2002. The authors have an obvious strength in their understanding of the localized, daily realities of teaching, where the great disparities across age groups, genders, school buildings, and individual learner needs meet top-down, provincially mandated and board-structured policies, creating endless “disconnects.” Information and communications technologies are the latest example of these politically charged policies. As they conclude, “macro policies rarely affect the kinds of practices they seek to regulate—the everyday and mundane—because they cannot and do not reflect how everyday experiences are formed, mediated, and reconstructed by the continuously shifting social, cultural, and institutional backdrop of schools and districts” (p. 147). The book is extremely effective at bringing the series of local, school-based issues associated with new technologies to the fore. For policy-making, it is critical to recognize that much of the evaluation of new technologies in the education system has been based on short-term, quantitatively driven measures of how computers and student access to them are “paying off” in the eyes of school officials, politicians, and parents. Policy Unplugged draws on a series of critical local issues that need to be part of any effective policy on ICT, including the realities of the actual culture of learning in our schools today. Part One of the book includes a critical analysis of the actual CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY – ANALYSE DE POLITIQUES, VOL . XXXIV, NO. 2 2008 276 Reviews/Critiques d’ouvrages spatial arrangements of our aging school buildings. Policies to address the “new knowledge economy” and to “reflect international and national student achievement standards” have resulted in top-down provincial and boardwide policies, largely ignoring the essential role of the teacher, the diversity and individualized nature of the curriculum in the classroom, as well as the critical role of professional development of our teachers. One of the most important contributions of this work is the assertion that teachers must have a central role in any effective ICT policy. The authors argue that professional development will have to recognize the largely ignored issue of gendered relationships with technology and the way in which males are privileged within most ICT policies. CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY – ANALYSE DE POLITIQUES, Part Two provides an updated context for policymaking in Canadian schools and school districts and how the new educational imperative of technology skills for the twenty-first century will pose a significant challenge for those who wish to bridge the policy gaps between teaching and technology. The authors offer a clear vision for policy-makers and a set of policy principles, should we ever hope to achieve world-class learning outcomes for our students. As Tip O’Neill suggested for politics many years ago, perhaps all effective ICT policy will be local, with people as the focus, rather than the technology. MICHAEL FOX, Department of Geography and Environment, Mount Allison University VOL . XXXIV , NO. 2 2008 Reviews/Critiques d’ouvrages Coasts under Stress: Restructuring and SocialEcological Health by Rosemary E. Ommer with the Coasts under Stress Research Project Team. Montreal and Kingston, London, Ithaca: McGill-Queens University Press, 2007, 574 pp. The title of this book might more appropriately be Coasts in Trauma. Stress is too mild a term for the massive depletion of natural resources and the social disintegration resulting from the social-ecological restructuring that is so well documented by Rosemary Ommer and the Research Project Team. The book is a state-of-the-art account of the overall health of Canada’s coastal areas, with a cohesive theory that helps to make sense of how it arrived at such an unhealthy condition. It is their comprehensive view of health, ranging from the health of ecosystems, specific natural resources and communities, geographic regions, and individual people, along with an analysis of the linkages between these various types of health, that makes this book a unique and important contribution for all those concerned with the future of Canada’s coastal areas. Their research is deeply interdisciplinary. The names of those comprising the Research Project Team is a twelve-page list of natural and social scientists, graduate students, research assistants, and staff. Their study area is British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador. The analytical framework of the book is resiliency theory, a theory that focuses on complex adaptive systems, social-ecological health, and cross-scale governance. Thus, the analytical approach of Ommer and the Research Project Team emphasizes the effects of social and ecological restructuring from the perspective of interactive processes, the health consequences of multiscale alignments or misalignments, and the multiscale governance models required for promoting resiliency. Restructuring is most simply understood as the effects of globalization resulting from neo-liberal policies, while scale occurs in temporal, organizational, and spatial dimensions. Two 277 other key elements in their approach is a community-based analysis and an examination of knowledge production. Therefore, as one example, the collapse of Newfoundland and Labrador cod stocks can be seen as resulting in large measure from various scale misalignments: the differing knowledge of scientists and local fishers (organizational scale) about cod in large fisheries management zones versus local bays (spatial scale), and the incapacity of scientists, managers, and fishers to adjust management and harvesting measures in response to data about short- and long-term trends (temporal and organizational scales). Coasts under Stress is divided into three parts. Part One is an historical overview, largely using case studies from fisheries, forestry, and non-renewable resources, that convincingly demonstrates the ups and downs in ecological and social health during pre-contact conditions, colonization, modernization, and globalization. Part Two describes the human impact of restructuring and social-ecological health. This is the most compelling section of the book. It begins with a detailed analysis of the restructuring of health care by the governments of British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador during recent decades. This discussion is followed by statistical analysis of the impacts of health care restructuring on health outcomes in these two provinces. The analysis is complemented by community-based studies and interviews on health, nutrition, and diet. Finally, these health studies are compared with the current situation of youth and their education. Throughout this section, linkages are made with previous discussions about ecological and social health. After a careful reading of this 140-page analysis, it is crystal clear how unemployed fishers, barren fishing grounds, closed emergency rooms in rural hospitals, the availability of groceries only in distant chainstore malls, increasing domestic violence, and massive outmigration of youth can be seen as pieces that fit perfectly into the same puzzle. CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY – ANALYSE DE POLITIQUES, VOL . XXXIV, NO. 2 2008 278 Reviews/Critiques d’ouvrages Part Three presents alternative governance options for Canada’s coasts. This section is less compelling and somewhat disappointing as there is a return to a more natural resource focus compared to the holistic notion of health in Part Two. Acknowledging the inadequacy of current federal policy, primarily as seen in the implementation of the Oceans Act, Rosemary Ommer and the Research Project Team propose a comprehensive notion of “co-management with stewardship” as the means of restoring ecological and social health. Co-management ensures that all levels of organizational scale are brought into the decision-making process, while stewardship gives a special place in this process to ecological restoration, community control of local resources, and a broad range of social values. It is, as they say, a combining of a top-down with a bottom-up approach. However, if it is the misalignments of scale that lead to disastrous consequences, then to avoid misalignments there must be a free flow of communication and cooperation both up and down the various levels of organizational scale. This study demonstrates that communities are already trying CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY – ANALYSE DE POLITIQUES, to take these steps, but it is not clear that there is any interest on the part of governments to move in the same direction. The authors’ call for a change in perspective in the corridors of power is likely to fall on deaf ears. Their focus on the co-management alternative points to a major gap in this book, namely, the absence of an Arctic Ocean perspective. Formal comanagement is well established between the federal, territorial, and aboriginal governments in the North, and First Nations’ values similar to or stronger than stewardship underpin the harvesting and governance activities of their people. Is there thus evidence for healthy social-ecological systems in the North? Whether the answer is affirmative or negative, Coasts under Stress offers a significant step forward in broadening the interdisciplinarity, comprehensiveness, and depth of the “new ecology” but provides little that is uniquely fresh in policy options. JOHN K EARNEY, John F. Kearney & Associates VOL . XXXIV , NO. 2 2008 Reviews/Critiques d’ouvrages In Search of Canadian Political Culture by Nelson Wiseman. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007, 346 pp. Wiseman’s provocative book expands our understanding of policy options in Canada in a most novel way. He paints a picture of our existing political culture by first rejecting any notion of constitutional change and largely questioning the usefulness of the Louis Hartz thesis as interpreted by Gad Horowitz and Kenneth McCrae. For example, Wiseman notes that Horowitz argued that social democracy in Canada is a function of the strength of toryism whose traditional focus on the collective is shared by socialists. Yet, Wiseman points out, Horowitz does not explain why Canadian social democracy is strongest in the West, where the Loyalist stamp is weakest. Likewise, Wiseman rejects Seymour Martin Lipset’s views on the origins and nature of Canadian agrarian radicalism and does not find Harold Innis’s staple thesis or the Marxian class conflict thesis very helpful. In looking at Quebec, Wiseman is more open to the Hartz-Horowitz hypothesis. He sees the shared commonality between the ancient régime conservatism of New France and modern socialism and uses it to account for Quebec’s passage beyond its liberal Quiet Revolution to social democracy. While largely dismissing these traditional theoretical ways of explaining Canadian political culture, Wiseman turns and examines Canada regionally and uses the five waves of immigration the country has undergone since its beginning to define and to knit these regions together. What is unique is this thread of immigration that he weaves through his analysis. He sharply differentiates English Canada from Quebec: immigration fed ideological development in English Canada, but in Quebec, it was internal, spontaneous combustion. Wiseman really sees Canada as a country of six regions. Unlike many scholars in the past, he does not seek commonality to overarch regional differences. Surprisingly, however, within his regional approach, he does not include any part of the coun- 279 try “north of 60” and thus leaves aside the three territorial divisions: Nunavut, the North West Territories, and the Yukon. Immigrants to the environmentally sensitive and resource-wise North have certainly transformed the political culture there, but Wiseman gives no explanation for the North’s absence from his discussion. In defining the various regions of the country, Wiseman begins with Newfoundland and Labrador. Seeing immigration as the defining factor in the determination of the political culture of Canada’s six regions, Wiseman views Newfoundland as an offshoot of the Irish and the West Countrymen of England. He sees the Maritimes as the oldest and most homogeneous of the regions of English Canada, a branch of New England. Quebec was retarded in its development by the culture of New France and, through a brief flirtation with liberalism, came to embrace socialism in the second decade after the Quiet Revolution. Because of the United Empire Loyalists, Wiseman understands Ontario as the counter-revolution of the United States of America. Then Wiseman deviates from the general consensus that usually clumps Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta together as a “prairie region.” Rather, Wiseman observes a Canadian midwest that includes only Manitoba and Saskatchewan. European and British immigration was a pivotal factor in the social democracy fortunes of this particular region. He sees Manitoba as the Ontario of the prairies, and Saskatchewan was shaped by British immigrants who brought British Labour success to the prairies. In his Far West region, Wiseman links Alberta and British Columbia as the upstarts. For him, Alberta is a splinter of the United States, especially the American Great Plains area, while British Columbia resembles Australia, with its resourcebased economy in far-flung places and the largely urban societies both past and present. Both see themselves as a new Eden where utopianism reigns. This Far West region is the most innovative and controversial, but Wiseman makes a very good case for joining these two provinces together. For example, he notes that socialism and the robust labour organi- CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY – ANALYSE DE POLITIQUES, VOL . XXXIV, NO. 2 2008 280 Reviews/Critiques d’ouvrages zations in British Columbia have ties to the United States just as Alberta has links with the American Great Plains culture with their potent democratic ideas. However, he does not neglect their differences either. Wiseman sees a pronounced secularism in British Columbia compared with the Christian fundamentalism in Alberta. However, the similarities are sufficient to join the two into one region, and today Albertans have more interaction with British Columbia than with their prairie neighbours. Wiseman uses Stockwell Day as a typical politician who has crossed from Alberta to British Columbia and finds himself at home in both political milieus. Based on secondary material, Wiseman offers a very useful, thought-provoking and fresh analysis of Canadian political culture. Wiseman’s analysis explains why it is so very difficult in Canada for a federal government to develop policy of a panCanadian nature. Because the waves of immigrants have not only arrived at different times throughout our history but have also tended to settle in specific CANADIAN PUBLIC POLICY – ANALYSE DE POLITIQUES, regions as each wave has appeared on our shores, deeply ingrained political and cultural differences have developed among regions. Consequently, even after compromise and negotiation between the various interested parties and federal and provincial governments have taken place, one region or another often feels alienated because, Wiseman claims, there is little commonality among the political cultures of Canada’s various regions. On the other hand, Wiseman shows why provincial governments are better able to develop policy that will satisfy and be accepted by the citizens under their jurisdiction. A shared political culture in the various regions allows for policy decisions to conform to the particular culture of any one province. Policy-makers in Canada will certainly find this book an essential read before embarking on their policy-making tasks. KENNETH MUNRO, Professor of History and Senior Director of Interdisciplinary Studies, University of Alberta VOL . XXXIV , NO. 2 2008