THE APPROPRIATE SCOPE OF CREDIT CARD SCHEME REGULATION American Express International, Inc.

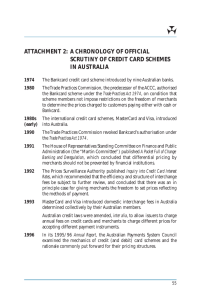

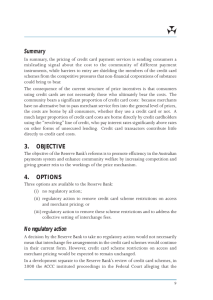

advertisement