Reform of Credit Card Schemes in Australia MasterCard International Incorporated March 2002

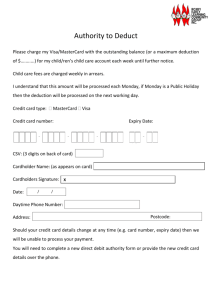

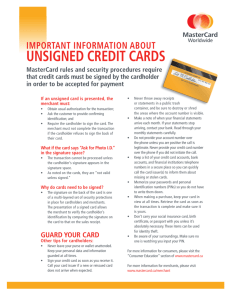

advertisement