Report Research Expert Practice in Physical Therapy 䢇

advertisement

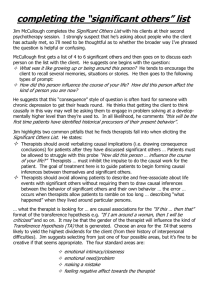

Research Report 䢇 Expert Practice in Physical Therapy ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў Background and Purpose. The purpose of this qualitative study was to identify the dimensions of clinical expertise in physical therapy practice across 4 clinical specialty areas: geriatrics, neurology, orthopedics, and pediatrics. Subjects. Subjects were 12 peer-designated expert physical therapists nominated by the leaders of the American Physical Therapy Association sections for geriatrics, neurology, orthopedics, and pediatrics. Methods. Guided by a grounded theory approach, a multiple case study research design was used, with each of the 4 investigators studying 3 therapists working in one clinical area. Data were obtained through nonparticipant observation, interviews, review of documents, and analysis of structured tasks. Videotapes made during selected therapist-patient treatment sessions were used as a stimulus for the expert therapist interviews. Data were transcribed, coded, and analyzed through the development of 12 case reports and 4 composite case studies, one for each specialty area. Results. A theoretical model of expert practice in physical therapy was developed that included 4 dimensions: (1) a dynamic, multidimensional knowledge base that is patient-centered and evolves through therapist reflection, (2) a clinical reasoning process that is embedded in a collaborative, problem-solving venture with the patient, (3) a central focus on movement assessment linked to patient function, and (4) consistent virtues seen in caring and commitment to patients. Conclusion and Discussion. These findings build on previous research in physical therapy on expertise. The dimensions of expert practice in physical therapy have implications for physical therapy practice, education, and continued research. [Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Shepard KF, Hack LM. Expert practice in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 2000;80:28 – 43.] Gail M Jensen Jan Gwyer Katherine F Shepard Laurita M Hack 28 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў Key Words: Clinical competence; Decision making; Physical therapy profession, professional issues. Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў I n almost every field of human endeavor there is interest in understanding expertise. The argument is made that knowing more about what experts know, how experts think, and how they perform in practice is essential to continued development of a profession and preparation of the next generation of professionals.1–3 We know very little about how experts practice in physical therapy, that is, what knowledge they hold, how they engage in clinical reasoning and decision making, and what beliefs and related behaviors they exhibit during their work with patients and families. Identifying and understanding these critical dimensions of expertise can give us guidance for the creation of entry-level and continuing educational programs and clinical residency programs as well as for structuring the clinical practice milieu to facilitate the process of expertise development. The practice of physical therapy is becoming increasingly complex. Rapid changes in the health care system are placing increased pressure on physical therapists for effective and efficient management of patients amidst high patient turnover. Patient diagnosis, prediction of prognosis, intervention, and patient-family education must be done quickly and accurately. The integration of examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention are advocated as part of routine patient/client management.4 Eddy5 asserts that medical clinical decisions about how to manage a patient/client require synthesis of information including the disease process, the patient, the signs and symptoms, interventions, values, and outcomes and are done with a great deal of uncertainty. All of this must be done (decision making) without knowing precisely what the patient has, with uncertainty of signs and symptoms, with imperfect knowledge of sensitivity and specificity of tests. . .incomplete and biased information about outcomes, and with no language for communicating or assessing values.5(p316) The same is true in the practice of physical therapy. Understanding how our expert practitioners see their role in health care, how they gather, sort, and apply information and knowing what beliefs guide their patient interactions will illuminate the practice of physical therapy. GM Jensen, PT, PhD, is Associate Professor, Department of Physical Therapy, School of Pharmacy and Allied Health, and Faculty Associate, Center for Health Policy and Ethics, Creighton University, Omaha, NE 68178 (USA) (gjensen@creighton.edu). Address all correspondence to Dr Jensen. J Gwyer, PT, PhD, is Associate Clinical Professor, Director of Doctoral Studies, and Doctor of Physical Therapy, Duke University, Durham, NC. KF Shepard, PT, PhD, FAPTA, is Professor and Director, Doctor of Philosophy Program in Physical Therapy, Department of Physical Therapy, College of Allied Health Professions, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pa. LM Hack, PT, PhD, MBA, FAPTA, is Associate Professor and Director, Department of Physical Therapy, College of Allied Health Professions, Temple University. Each author contributed to concept and research design; writing; data collection and analysis; project management; fund procurement; provision of subjects, facilities and equipment, and institutional liaisons; clerical support; and consultation (including review of manuscript before submission). This research was funded by the Foundation for Physical Therapy. This article was submitted February 9, 1999, and was accepted August 12, 1999. Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 Jensen et al . 29 Studying Expertise The first generation of theories of expertise emphasized the central importance of problem-solving skills. The expert was someone who held a set of reasoning strategies that could be used to solve problems.6,7 In medicine, investigators studied the relationship between clinical problem solving and physicians’ performance8,9 and this led to an increased emphasis on assessment and teaching of problem-solving skills.10,11 For example, hypothetico-deductive strategies (ie, where the clinician transforms an unstructured problem into a structured one by generating a limited number of hypotheses and then using them to guide further data gathering) were advocated as a method for teaching problem solving.9,12 Subsequent studies demonstrated, however, that the use of a formal hypothetico-deductive strategy did not distinguish successful from unsuccessful clinical problem solving. Individuals with varying levels of expertise were found to not differ in the strategies they used nor in their depth of process but in their recall of meaningful, selective knowledge.11–13 A second generation of theory on expertise then emerged where content knowledge and its structures were seen as essential components of the clinical reasoning process.7,12,13 Researchers argued that differences between experts and novices lay primarily in experts’ recall of meaningful relationships and patterns, that is, in the structure of the knowledge rather than in a problem-solving strategy applied to the problem. In addition, they postulated that problem-solving expertise was case specific and highly dependent on the clinician’s mastery of a particular content domain. Despite 2 generations of theory development in expertise, there are still many aspects of expertise that we have neither adequately identified nor understand. Currently, a third generation of researchers has been studying what experts in the health care professions actually do in practice.13,14 Much of this research has focused on 2 broad categories of cognitive science: (1) investigation of the process of reasoning and (2) understanding the structure and use of knowledge in the decision-making process. This research has traditionally been done by contrasting performance of groups who differ in knowledge and experience (eg, physicians with students, specialists with generalists) in laboratory-based tasks that represent practice.1,3,13 Study of Expertise in Physical Therapy In physical therapy, there has been interest in applying the hypothetico-deductive model to the clinical reasoning processes used by physical therapists. Payton,15 who studied the clinical reasoning process of 10 peerdesignated expert physical therapy clinicians, reported the use of a hypothetico-deductive model similar to 30 . Jensen et al findings in medicine. In their comparative study of 11 expert therapists and 8 nonexperts, Rivett and Higgs16 found that all therapists working in manual therapy generated hypotheses consistent with the use of hypothetico-deductive reasoning process. Both of these studies focused on the clinical reasoning process, with little emphasis on the type of knowledge used in the reasoning process. May and Dennis,17 in a survey study of American and Australian physical therapists who were considered to be expert clinicians by their peers, described the use of different cognitive processing styles for different clinical problems. Expert therapists in the orthopedic area reported more frequent use of an information processing style, where judgment is suspended until all data are gathered and then a systematic approach is applied. This group’s cognitive processing style was in contrast to that of therapists working in the neurological area, who reported more frequent use of a perceptive or intuitive data-gathering style, that is, seeking and responding to cues and patterns as they gather the data. These selfreport data from therapists provide evidence that cognitive processing styles may vary across clinical specialty areas; yet, whether this difference in cognitive processing styles actually occurs in clinical practice remains unknown. A recent qualitative study of clinical decision-making processes of experienced and inexperienced pediatric physical therapists by Embrey et al18 focused on clinical reasoning and domain-specific knowledge in pediatrics. They described similarities and differences between experienced and inexperienced clinicians on 4 characteristics of clinical decision making: (1) movement scripts (movement patterns common to children with diplegic cerebral palsy) as part of the knowledge structure, (2) rapidly occurring procedural changes within the decision-making process, (3) the importance of psychosocial sensitivity for positive interaction, and (4) the necessity of self-monitoring through selfassessment. The findings of psychosocial sensitivity and self-monitoring are consistent with previous work done on features of expert practice in physical therapy.19,20 Embrey and colleagues proposed that movement scripts may be part of the knowledge structure used in clinical decision making. This study provides additional insight into clinical decision making in one specialty area. The data, however, were obtained by a retrospective thinkaloud procedure, removed from the clinical decision making that occurs during practice. In physical therapy, the question of knowledge used in clinical practice continues to be examined.21,22 Higgs and Titchen21 described 3 types of knowledge: propositional (derived from research), professional or craft Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў (derived from practice), and personal (derived from self). The authors suggested that a deeper understanding of the nature of knowledge underlying clinical practice is needed. Studying Expertise in Practice Settings Researchers studying expertise in other health care professions, including nursing,2 medicine,13 and occupational therapy,23 have argued that research must also be done in the actual practice setting, the clinic, using qualitative research methods. This emphasis on understanding everyday practice is consistent with the argument that a professional’s skillful action is adapted to the context of practice and that learning from one’s practice is a legitimate source of knowledge.2,21,23,24 Grounded Theory Approach to Studying Expertise in Physical Therapy Practice Chenitz and Swanson described grounded theory as a “highly systematic research approach for the collection and analysis of qualitative data for the purpose of generating explanatory theory that furthers the understanding of social and psychological phenomenon.”25(p3) Grounded theory has its roots in the symbolic interaction traditions of sociology and social psychology.26 This perspective is similar to other naturalistic traditions where the researcher seeks to understand human behavior within a natural context and from the participant’s viewpoint. If a researcher is looking at a phenomenon that is a process or experience over time, Morse27 suggested that the research strategy of choice should be grounded theory. In grounded theory, the researcher does not begin by speculating about the theory but rather proceeds primarily through an inductive process to study the human experience and, from that, extrapolates theory. Using the grounded theory approach, we have gathered data, made theoretical interpretations, and then returned to the field to collect more data to reaffirm our interpretations and probe new areas suggested by the data analysis.28 Along the way, we have read whatever we could find related to expertise to assist us both in understanding our work and in placing this work into the larger context of understanding how health care professionals gain and use expertise.1,2,14,23,29 The purpose of this study was to identify the core dimensions of clinical expertise in physical therapy practice across 4 clinical specialty areas: geriatrics, neurology, orthopedics, and pediatrics. Method Sample The subjects for the study were 12 physical therapy clinicians who were identified by their peers as experts, Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 3 each who specialized in the practice areas of geriatrics, neurology, orthopedics, and pediatrics. A nomination and selection process was used to identify these expert practitioners. Officers of the American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA) sections for pediatrics, geriatrics, and neurology were solicited for nominations of expert practitioners, and a list was generated for each specialty area except orthopedics. A recent Delphi survey of leaders of the Orthopaedic Section and the manual therapy community was used to generate the list of experts in orthopedics. Subject selection criteria developed in previous work on expertise11,19,20 were used to identify potential experts. These criteria were: having 7 or more years of clinical practice, being involved in direct patient care at least 50% of the time, having completed formal or informal advanced work in the specialty area, and being someone to whom the nominator would refer a patient with complications or a family member for care. The focus of this study was on describing the dimensions of expert practice; therefore, there was no attempt to determine whether these experts achieved better outcomes with their patients or were able to manage patients more expeditiously. Final selection of experts was done by selecting those nominees who received the most nominations based on the criteria and who were geographically located in a region close to the investigator. Each investigator obtained institutional review board approval within her academic institution as well as within hospital settings where some of the expert clinicians worked. All expert clinicians and patients who were observed as part of the study signed consent forms. Research Design The basic research design for this study was a multiple case study design using a within- and cross-case analysis.30 We began the study by having each investigator collect data on one expert therapist and by writing up these data as a single case report. Each case report contained 6 components: (1) personal background of the expert and summary of professional development, (2) identification of the types of knowledge used in practice and sources of knowledge, (3) description of the clinical reasoning processes, (4) description of the expert’s philosophy of practice, (5) description of the expert’s disposition, personal values, and beliefs, and (6) identification of physical therapy skills. As we continued to gather data on other experts and write case reports (each investigator gathered all the data in one specialty area), we began to look for similarities and differences across the case reports of the 3 therapists in each clinical area. Then, for each of the clinical areas, we wrote a composite case study that represented a composite description of expert practice in that clinical area. A final component of the multiple case study design was to develop a model (grounded theory) based on similari- Jensen et al . 31 was the use of clinical exemplars. Participants were asked to provide examples (exemplars) of critical events in their professional development.33 Figure 1. Multiple case study design. ties across all 12 case reports (Fig. 1). The mechanism for identification, conceptualization, and elaboration of the cases to a larger conceptual framework was a series of researcher and consultant meetings after each round of data collection.30,31 Data Collection Methods The 4 investigators in this study had extensive experience in fieldwork methods and an 8-year history of training and collaboration as a team studying the nature of expertise in physical therapy.19,20 We have used successive data sets from a series of studies to reaffirm and revise an evolving conceptual framework that focuses on the clinical performance behaviors of peer-designated expert clinicians.19,20,28 In this study, each investigator followed a similar time and format schedule for data collection. Qualitative data collection methods included interviews with peer-designated expert clinicians, on-site nonparticipant observations, videotaping patient treatment sessions, and review of documents (eg, published papers, teaching materials, patient records). Data were collected until saturation occurred, that is, until no new information was retrieved from the data collection. Within the interview sessions, structured tasks were used to aid the clinicians’ recall of important events in their professional growth and development. One structured task was the use of a résumé sort. Participants were asked to “sort the items on their professional résumé into groups that reflected the relative degree of importance of each item to one’s professional growth.”32 Another structured task 32 . Jensen et al A video recording was used of the initial patient evaluation, at least one treatment session, and the last patient visit during a single episode of care for at least 3 patients treated by each clinician. We defined an episode of care as all physical therapy visits provided for one patient during a “single episode” or up to 3 months of care for patients with chronic impairments. These videotapes were then replayed for the therapist and used as the basis for debriefing interviews focused on the knowledge and clinical reasoning process the therapist was using during the treatment sessions. We generated an interview guide that each of us followed in conducting our debriefing interviews with the therapists (Tab. 1). In choosing to study an episode of care with various patients, we hoped to collect data that could capture the way in which therapists routinely think about and engage in patient management. Data Reduction and Analysis The data reduction and analysis process was organized around 4 major cognitive processes that Morse34 identified as inherent in the qualitative data analysis: comprehending, synthesizing, theorizing, and recontextualizing. The steps of this process and specific tasks are delineated in Figure 2. In the initial phase of the data analysis (comprehending), each researcher transcribed and coded all interview, document, and observational data collected on the first therapist case.31 Initial coding was done using the broad categories identified in an earlier conceptual framework.20 The research team then compared and discussed the coded data and developed revised categories that more precisely identified the data content. In qualitative research, this is the process of moving from open coding to axial coding.35,36 Strauss and Corbin35 described open coding as the initial coding of the data set. Axial coding puts data together in new ways “by making connections between a category and subcategories.”35(p97) The new categories and subcategories developed during our discussion formed the revised coding scheme that was used in the subsequent rounds of data collection (Tab. 2). The second stage of data reduction (synthesizing) was the writing of case reports for each of the 12 peerdesignated expert therapists. Each researcher used a Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў Table 1. Interview Guide for Videotape Playback of Episode of Care Sample questions asked as expert clinician and researcher are viewing videotape: 1. Tell me what you were thinking about as you completed your evaluation of the patient? What is your diagnosis? What evidence did you use? How do you know what information to focus on? Where did you learn that? Where will you go next? 2. Tell me what is going on with this patient. What is your prognosis? How did you reach that conclusion? What evidence did you use? How did you know to use that evidence and where did you learn that? 3. Tell me about your most difficult problem with this patient. How did you identify the problem? What evidence did you use? What was your strategy for solving the problem? How did you learn to do this? 4. Tell me how you go about making clinical decisions with this patient? What is your approach? Describe an example as we go through the videotape. Is this process of making a decision different for you now compared with when you were a novice clinician? What are the differences? 5. What do you think your best patient care skills are? What knowledge do you draw on as you execute these skills? (Look at videotape for specific examples.) 6. How do you know you have been effective in your evaluation and treatment of this patient? 7. What would you tell a student about how to go about decision making in this patient care environment? Would what you tell a student differ from what you actually do? How would it be different and why? common case report outline that followed the coding scheme categories. Using a common structure for the case reports facilitated the data reduction process and allowed us to look across individual case reports in a comprehensive fashion.31 A copy of the case report was sent to each peer-designated expert for review and verification (member check). Any comments received were integrated into a revised case report. During the third phase (theorizing), we met as a research team with each investigator contributing a preliminary analysis and a set of working assertions across her 3 cases. All case reports were read by all of the researchers and reanalyzed by additional comparison and interpretation across cases. Conflicting interpretations of the cases were discussed, and consensus was reached when case data from most of the cases were found. This analytic strategy is called “pattern matching and explanation building.”30 An additional component of our data analysis and theory development at this stage was the use of 3 expert, non–physical therapist consultants who were university professors and well published in the areas of decision making, medical expertise, and qualitative research. After we identified their expertise from published research, we contacted them, and they agreed to provide consultation to our study. These experts met with us at the beginning of the project and after data collection on 2 therapists. They also reviewed and commented on our case reports. Their role was to provide us with an external perspective in building the theoretical formulations from the data and to afford us an external peer review for our case construction and interpretations.37,38 These consultants were extremely valuable in identifying our blind spots, challenging our assumptions, and moving our work to a higher conceptual level. The fourth and final stage of data reduction (recontextualizing) was the construction of 4 composite cases, Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 each based on the 3 specialty area case reports. A cross-case analysis of the composite cases was done to develop a grounded theory that describes the core dimension of expert practice across these cases.36 Standards of verification. Although experimental and quasi-experimental research refers to reliability and validity, naturalistic research, which relies on qualitative data, refers to the dependability (similar to reliability), credibility (similar to internal validity) and transferability (similar to external validity) of the data.37 The verification process used in this study included the following methods to ensure dependability and credibility of the data30,31,37–39: 1. Prolonged engagement and persistent observation in the field. 2. Triangulation of the data through the use of multiple data sources, multiple methods, and multiple investigators. For example, if multiple expert clinicians tell multiple investigators in interviews how important teaching is to their work, if teaching patients and families is observed in nearly every patient encounter, and if the videotaped data reviewed by others clearly portrays teaching, then the data are “triangulated,” and we can conclude with reasonable assurance that the centrality of teaching to the practice of these expert clinicians is both credible and dependable. 3. Member checks. Each of the case reports was returned to the expert clinician to review and make changes relative to accurate portrayal of both content and meaning. 4. Peer review or debriefing at each stage of the case construction. By reviewing each other’s data and assertions and by having our consultants review and comment on the data, our theory development blind spots and biases were brought to light and challenged. Jensen et al . 33 Results Clinician Profiles A professional profile was compiled on each of the 12 clinicians (Tab. 3). These clinicians had practiced in a diverse array of clinical settings, with their clinical experience ranging from 10 to 31 years of practice. All of the clinicians had acquired specialty education through a combination of shortand long-term continuing education courses (eg, clinical residency programs of 3 months’ duration or longer). All of the clinicians were actively involved in teaching in a variety of settings, and 11 clinicians were active members of APTA. Conception of Physical Therapy How do the peer-designated experts view being a physical therapist? The Figure 2. theoretical model in Figure 3 repreCognitive processes involved in qualitative data analysis. Adapted from Morse.34 sents 4 major dimensions of expert practice in physical therapy that were identified as a result of our data analy5. Negative case analysis. By looking for data that did sis: knowledge, clinical reasoning, movement, and virnot fit the direction of the ongoing analysis, each tues. At the center of this expert practice model is the analysis was challenged. The results, therefore, reflect therapist’s conception of practice that emerges from the the preponderance of data rather than isolated 4 dimensions. This conception of practice represents the instances. expert therapist’s vision of what it means to practice physical therapy. This conception includes the thera6. Rich, thick description. Much of the data is presented as pist’s beliefs about the role of physical therapy in health direct quotations, which are considered low-inference care and how she or he works with patients and families. data. That is, no inferences are made without supporting data taken directly from the respondents. PresentaThe expert therapists in this study shared a relatively common understanding of their role as physical theration of thick data allows the reader to determine the credibility of the researchers’ interpretations. pists, regardless of clinical specialty area. Practice begins and ends with patients. This understanding translated Theoretical Model of Expert Practice into listening intently to patients’ stories, understanding Evidence drawn from the 4 composite case studies was the context of the patients’ lives in designing and implementing treatment programs, and collaborating used to illustrate the 4 dimensions of expert practice. with and teaching patients and families about regaining These data were originally drawn from hundreds of function and enhancing their quality of life. In addition, pages of transcripts, observational data, interpretive these therapists did not judge difficult patients or label memorandums, and videotaped recordings. Because of them as a “noncompliant or malingering,” but instead manuscript page limitation, examples of representative assumed responsibility for trying to solve what they data are included in this article. Because interview called “complex clinical cases.” Discussion of these 4 quotes are the most concise form of data, we have chosen them to provide illustrative data. The reader dimensions of expert practice illustrates how this conshould be aware that although single quotes are used, ception of physical therapy is constructed. the data have been well triangulated to maximize credibility and dependability. Readers interested in reading Multidimensional Knowledge Base the composite cases that present the in-depth findings This group of peer-designated experts had a deep underfrom each of the specialty areas as well as expanded standing of their clinical specialty knowledge that was interpretation of the data are referred to the book multidimensional and centered on the patient. Expertise in Physical Therapy Practice.40 Although professional education was an initial source of 34 . Jensen et al Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў knowledge and the beginning point for practice, it was not enough; they were highly motivated to continue learning. The first year out of school, I immediately felt like I had to go back to the things I learned in physical therapy school and refile everything, because everything I learned was from one perspective and I needed to immediately pull it out by diagnosis. . . .I realized when I did that what I had for any given diagnosis was incomplete. . . , so I went to the library and started looking up spina bifida or any diagnosis and just pouring through the articles. This was a completely different type of learning, and I just loved it. (Pediatric Clinician [PC]) I was at this clinic doing what I had learned in school and from a long-term course, and what I would find is that patients I would treat and could not help would go to see another practitioner. Then, in 2 or 3 months, I would see them and they would say they saw this practitioner and were helped in 1 or 2 visits. I said to myself, “I have to find out what that person is doing.” (Orthopedic Clinician [OC]) Table 2. Revised Coding Scheme Concept Definition Background information Personal and professional background and experience Conception of physical therapy How therapists think and talk about their work; values and beliefs that underlie their actions, their views about health and illness; how one actually conducts practice Clinical practice and reasoning Evidence of decision making; kinds of thinking and reasoning; philosophical school of thought; evidence of reflection Knowledge domains Content Knowledge specific to specialty or physical therapy Patients Knowledge of human behavior; insights into patients Teaching Knowledge of teaching patients Knowledge of self Knowledge of own self; confidence; growth as person and professional Knowledge of context Knowledge of the larger picture; role of work, environment; health care system Sources of knowledge Mentors Professional education Patients Colleagues Self-education Reading Physical therapy skills Clinical mentors were another source of knowledge and were instrumental in facilitating the learning process of these expert clinicians. They admired these mentors for their skills and ability to help patients, particularly the difficult or tough cases. Usually, it was not just one mentor, but a series of mentors who were present at different points in their career. These mentors stimulated their thinking and helped them understand and sort out complex cases. This person was a powerful role model for me. She was thinking in ways that other people weren’t. She was very criticized for her research, but definitely a hard thinker. (Neurologic Clinician [NC]) I basically worked 7 days a week. . . .You were asked to take it all in and synthesize the information with a live patient. You were forced to make decisions, and you made a lot of mistakes, but you learned. I think the clinical mentorship is what helped me learn light-years faster. (OC) One of the most important sources of their knowledge was their patients. Listening to patients was an essential evaluative skill. Our videotapes of experts practicing demonstrated consistent active listening skills: keeping eye contact; sitting at the same level as the patient; Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 Evidence of use of manual skills; technology; equipment; use of touch maintaining an intense, focused interaction with patients; and building their questions on the patient’s responses. A central focus of the patient interview for the experts was to have the patient tell his or her story rather than having the therapists initiate a series of questions to which the patient must respond. Experts confirmed this in their interviews. You get a lot of good information. . . .You just let your patients talk and give it to you as they want it to come out. (OC) One thing that I think I’ve really improved on with practice . . .and because of specific course work I’ve had with specific people is shutting up and listening. . . , and I’ve gotten much more information from listening than I ever did from structuring my questions. . . .It really isn’t a problem getting the parents to tell you about the child. It’s mostly just giving them the permission to tell you. . .and acknowledging, honoring what they are saying. (PC) Their use of knowledge goes beyond the patient’s movement problem or mechanism of injury to understanding the patient, their support system, and activities at work Jensen et al . 35 Table 3. Professional Profile of Peer-Designated Expert Therapists (n⫽12) Clinician and Years of Clinical Educationa Specialty Area Experience (Degrees) Practice Settingsb Advanced Specialty Educationc Teaching Experienced Professional Involvemente Orthopedic clinician 1 31 BS MS Acute care Rehabilitation HMO PP (owner and corporate) CE LTC CE Clinical faculty (LTC) APTA IFOMT Orthopedic clinician 2 19 BS MS Acute care HMO PP (owner) CE LTC CE Clinical faculty (LTC) APTA IFOMT Orthopedic clinician 3 31 BS Acute care Rehabilitation PP (owner) HMO Military CE LTC CE Clinical faculty (LTC) Academic APTA IFOMT Pediatric clinician 1 15 BS MS Pediatric clinic/school Acute care CE NDT CE APTA Clinical instructor NDTA (CI) Academic Pediatric clinician 2 30 BS MS PhD Rehabilitation Acute care UAPP PP (owner) CE PNF CE CI Academic APTA Pediatric clinician 3 24 BS MS PhD Adult (long-term care) Acute care UAPP Consultant (state board of education) CE NDT CE CI Academic APTA NDTA Geriatric clinician 1 23 BS MS MPA Acute care Rehabilitation Home care Nursing home Military GCS NCS CE CI CE APTA Geriatric clinician 2 25 BS Certificate Outpatient practice Home care Nursing home Military CE CI CE APTA Geriatric clinician 3 36 BS Acute care Nursing home Geriatric center CE CI CE None Neurologic clinician 1 10 BS MS Rehabilitation Outpatient practice Home care CE NCS (pending) CI CE Academic APTA Neurologic clinician 2 15 BS MS Research laboratory Rehabilitation Acute care NCS CE Academic CE APTA Neurologic clinician 3 13 BS Certificate MS Rehabilitation NDT CE NCS CI CE Academic APTA a BS⫽Bachelor of Science, MS⫽Master of Science, PhD⫽Doctor of Philosophy candidate, Certificate⫽certificate in physical therapy, MPA⫽Master of Public Administration. b HMO⫽health maintenance organization, PP⫽private practice, UAPP⫽university affiliated pediatric program. c CE⫽continuing education, LTC⫽long-term course, NDT⫽certified in neurodevelopmental treatment, GCS⫽geriatric certified specialist, NCS⫽neurology certified specialist, PNF⫽certified in proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation. d CE⫽continuing education, LTC⫽teaching in long-term course, CI⫽teaching in clinical education, Academic⫽teaching in academic classroom. e APTA⫽American Physical Therapy Association, IFOMT⫽International Federation of Manipulative Therapists, NDTA⫽Neurodevelopment Teachers Association. 36 . Jensen et al Physical Therapy . Volume 0 . Number 0 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў and home. Knowledge embraced by experts in pediatrics, neurology, and geriatrics included normal and abnormal physical, psychological, and social development as well as psychomotor status. Today, I was doing a consultation with a much richer background of knowledge, not just about child development, but about family issues, about adulthood interactions, about early intervention policy at the national level. . .a general theoretical base about seeing the child as an integrated whole. (PC) Premorbidly, this patient (with a severe cerebrovascular accident) sounded like a real card. He is in his 80s, but he went dancing probably 3 or 4 nights a week. . . .So premorbidly he was very active. (NC) Often people come [to a physical therapist] after they’ve had injuries, and they’re fearful, depressed, thinking “This is the end for me.” And I say, “Wait a second, you’ve got this life expectancy ahead of you. How are you going to live? Are you going to succumb to this injury, or are you going to try to rehabilitate to the highest potential?” (Geriatric Clinician [GC]) For peer-designated experts in orthopedics, although there was acknowledgment of understanding relevant social and psychological factors, the specific focus was on the movement problem and teaching patients to manage this problem. We look at the problem and ask what is it that is keeping this patient from moving? Is it physical? Is it psychological? Is it emotional? Sometimes it is emotional, and by that I mean they have a belief system that if they move they will get worse. . . .What they are here for is to understand their problem and become their own therapist. The patient must be involved in his or her own therapy and must understand what I am doing and become part of what I am doing. (OC) Peer-designated expert clinicians were much more focused on the knowledge they had gained learning from patients in their practice than on knowledge gained from traditional academic content areas such as anatomy, biomechanics, or pathology. They had compiled both breadth and depth of clinical knowledge that had evolved through their own thinking about practice (reflective process).24 Interpretation of a patient’s signs and symptoms, management of a patient through consultation with other professionals, and analysis of what worked and what did not work have significant meaning for these experts. [This expert spoke of grappling with understanding all of the body’s systems because the patient should be viewed as a whole person.] I try to see the musculoskeletal folks having some neurological organization to that musculoskeletal performance or that biomechanical performance. . . .I don’t think the neurological system and musculoskeletal Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 Figure 3. Core dimensions of expert practice in physical therapy. system are separable. . . .To learn something, you’ve got to start to categorize or discriminate, but understand the whole patient. (GC) I feel sometimes I form opinions pretty quickly about certain patterns. I get an intuitive feeling about problems after I have observed patients for awhile. . .people’s (clinical) problems and how well they will typically do and what to expect. (NC) When I hear information that conflicts with what I feel I’ve known to be true when I actually have watched a child, then I do question it. I want to explore it further before I just take information from someone else if it really conflicts with what I’ve experienced in the clinic. (PC) I constantly try to make sense to see how certain clinical pictures behave. If you go in and listen to the patients, they will tell you. (OC) Thus, these peer-designated experts continually expand their knowledge base by thinking critically about their practice. Patients are a powerful, central, valued source of clinical knowledge. Clinical Reasoning: Contextual Collaboration Collaboration between therapist and patient was central to the clinical reasoning process. The patient as a valued and trusted source of knowledge was a critical focus in the assessment process. Therapists focused on the patient first as a person. For example, what valued activities or goals did the patient have, and how did movement problems interfere with those activities? What kind of support did the patient have at home and work? Patient or family data were selectively gathered and specific to the case. Jensen et al . 37 You have to learn what the patient wants within the first 5 minutes because then you can focus your patient and say, “If we can change this and this, we might be able to get you back to horseback riding.” What are your hobbies? Are you doing them now? Can you work? What do you expect from me? What do you do? These are the kinds of questions to help you focus on what is meaningful to the patient. (OC) I think about making the task challenging to patients but at the same time enabling them to carry out the activity. I am always thinking about the long-term goal and working in that direction, trying to stimulate context, the environment as much as possible even if I am in the clinic. (NC) For these peer-designated expert clinicians, the medical diagnosis was a supplemental, additional piece of data, but not as central as what was happening with the patient functionally. The diagnosis [medical] itself is not as important as functionally what am I seeing that is happening. I like to know the diagnosis, especially when it comes to fractures and other conditions. . . ,but what is the reason their mobility is jeopardized? Is it a little bit of arthritis? Is it a little bit of neurological problems? Is it a little bit of stenosis? (GC) Once the problem(s) are identified and the context understood, the therapist engages both in collaborative problem solving with the patient and family and in educating them about movement and function as the intervention proceeds. I feel I spend the majority of time explaining to people what the problem is and then teaching them the ideas behind the therapy and then getting them to help me design their exercise program. They do all the work. When they come back, I check their progress. The more I explain to them the idea behind the intervention, the more they buy into it. (NC) A parent knows a child better than anybody who sees a child once or twice a week. And I really have to respect their instinctive ways of interacting with their kids. (PC) The therapist is accountable to the patient for the success of the program. It must make sense to the patient, or the therapist should answer questions until it does make sense. The success of the treatment depends upon the effectiveness of the patient’s role as patient/therapist. Patients must be in a position of control in the treatment process and must be willing to make changes in both behavior and lifestyle that are often necessary to achieve maximum recovery. (OC) As a physical therapist, you teach, and knowing how to teach is so important and enables you to be more successful. . . .If the patient does not understand what is happening to himself or herself, then the patient cannot make the necessary changes in behavior nor can the patient fully comply with the therapist’s activities. (GC) 38 . Jensen et al In their clinical reasoning process, these therapists were not afraid to be innovative and then evaluate and learn from their ongoing reflective process. They were challenged by their patients and welcomed the opportunity to learn from their patients. You learn to teach yourself. You need to ask questions, to think about what you are doing. I can see 2 people with a vestibular injury, and all their test results look the same. And these 2 people are completely different in terms of how they’re doing with treatment. Why is that? How can I explain that? Trying to figure it out helps you to begin to identify the problem, and that makes for good scientific inquiry. (NC) Movement: A Central Focus and Skill Movement was a central focus for all of the therapists studied. In the data gathering process, the therapist’s hands-on skills and assessment of movement was done through palpation and touch. I have a tremendous memory for how the child feels in my hands, and I often don’t see these kids for 6 months. I make notes after an examination. I’m glad to have my notes, but I trust my memory. (PC) I try to use touch a lot. It’s one of the first things that attracted me to physical therapy as opposed to medical school. And that is how we get to know our patients. We handle our patients. (GC) I have to feel what the patient is doing. Somebody will say, “Well, what do you think is wrong?” or “What can I do to make his gait better?” and I say, “Well, I don’t know, let me feel.” And then I can say, “There’s not enough weight shift. You need to facilitate this aspect of the movement and so on.” (NC) In pediatrics, play was used to evoke movement for evaluation and treatment. The experts provided an explanation for the importance of play that was more encompassing than fun and movement. See, now he’s starting to play with me, he is starting to play with my face. He wants me to puff air into my cheeks, and you know that silly game kids do. See, I feel that level of trust is just worth a million dollars. And now we are getting all the physical stuff we need. (PC) Function was considered the reason for the focus on movement. Returning the patient to a prior level of function or designing exercises that fit with the patient’s work or home environment or avocational activities was a continual focus. [From video observation] You see here I am allowing the patient to move the way she wants to move. [Patient is going down stairs by leaning forward using both handrails and descending step over step.] I have had patients who have Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў never gone up their stairs step over step with alternating legs, so I’m not going to teach them something new. (NC) [From video observation] Our goal here is to get you back to golf. [Therapist demonstrates the exercise to the patient.] Now let’s try that again. You are not strong enough yet to go low. (OC) Use of equipment, either in the clinic setting or for home programs, was very limited. Patients were treated with the therapists’ hands and instructed in exercise programs that were usually few in number, simple, and specific to functional movement. I look at the patient as being a mystery. I love to get a new patient because it is a new problem to solve. It is exciting, and if it wasn’t, I wouldn’t be practicing today. (OC) I don’t think I’ve ever reached a point where I was what you’d call burned out. (GC) I get nourishment from my teaching and my writing and my research. . . .It helps my thinking with my patients. (GC) The only part I can’t tolerate is feeling that I’m not doing a good job for the patients. That’s the part I can’t tolerate. (NC) Home exercise programs often used readily available items in the home environment and were often a vehicle of collaborative problem solving for the patient and therapist. Consistent with their interactions with patients was the experts’ ability to communicate a sense of commitment and caring about the patient. These therapists saw patient advocacy as a vital professional role, as demonstrated by the amount of time they spent working to get what was best for the patient through telephone conversations with case managers, writing additional letters or documentation, or serving the local and professional community in policy areas. I am of the belief that the majority of people will not do a lot of exercises. Part of the (physical therapy) diagnosis is done with exercise. Exercise helps me decide what is wrong with the patient. When I am not really clear, I give them one thing to do at home, and then I will get more information. I tell them they learn and I will learn from this exercise. (OC) I expect patients to be better within a certain this period of time, and if it doesn’t happen, they call me. This call method has evolved over time and gives the patient a process for thinking about where I can assist. Otherwise, I am doing nothing more than a person who hands out a sheet of paper and says go home and do your exercises. (OC) Beyond demonstrating, guiding, and facilitating functional movement in patients, all of the therapists used their hands to communicate with patients (eg, for reassurance, facilitating safety, and comfort and praising). Touch was often accompanied by congruent verbal responses. I have spoken with the MD at the rehab center who is following the patient and told her about the discharge from home care and my anticipation that she would be followed by outpatient therapy. The MD said she would write the prescription. Then I made a follow-up call to the secretary. The patient did not have the prescription yet from the MD. So a week and one half later, I made another contact with the physician, and she wrote it then while I was with her. Then I checked with the secretary, and she still didn’t have the prescription. Now, I am going to have to call the MD again. (NC) Well, I was cursing my physical therapist when she was making me pick up things off the floor. But then I dropped my car keys in the parking lot, and I was saying, “Thank you, thank you.” (Patient of NC) [From an observational memorandum] The therapist demonstrated a masterful touch in doing a neck massage as she prepared to do cervical traction with an outpatient. As she carried out soft tissue work, her voice softened and her conversation turned to items of personal interest to the patient (rather than discussion of the patient’s health problem). The therapist beamed with joy as the patient responded to this touch by relaxing and allowing soft tissue mobilization. Virtues: Caring and Commitment The dimension of virtues refers to personal character traits and personal attributes we observed in the expert therapists we studied. These experts all set high standards for themselves and were driven to stay current in their specialty area. They were continually intrigued by the challenges of clinical practice and strongly committed to doing what was best for the patient. Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 We have been in this community 15 years, and I know this patient. I have this attitude that when people come to my office, they become part of my family. (GC) Discussion The purpose of this study was to identify the dimensions of expert practice in physical therapy across 4 specialty areas using a series of qualitative case studies. The multiple case study approach allowed us to build on the foundation provided by previous work on expertise1–3,19 –20 and to generate grounded theory on expert practice in physical therapy.28,35,36,40 Jensen et al . 39 Knowledge and Clinical Reasoning Knowledge and clinical reasoning are both critical elements of expertise. One fundamental difference between experts and novices is the knowledge they bring to bear in solving problems.1,3 For these expert physical therapists, the primary component for both the use of knowledge and clinical reasoning was the centrality of the patient. Although the knowledge they used in practice was multidimensional, the patient was a key source of knowledge. We found our therapists engaged in intensive listening to patients and working hard to identify not only the movement problem but also what would be necessary for the patient to succeed in overcoming the problem. They are proficient at selfmonitoring skills and know when to selectively gather data or listen intently. When these peer-designated expert clinicians were asked how they know what to do, their responses were often related back to the patient and their prior experiences with patients and families. These therapists welcomed the challenge of tough cases and were comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. A growing body of expertise literature in physical therapy15–20 and the professions41,42 emphasizes the importance of metacognition, that is, self-monitoring one’s thinking (cognition).3 Experts use this process in order to detect inconsistencies or links between the data gathered, what they know from experience, and a critique of their reasoning processes.3,42 We also witnessed a process of collaboration between therapist and patient during the clinical reasoning process. The diagnostic process was not emphasized as a central aspect of patient management; what counted was patient function and understanding the context or the social and psychological conditions and events that were central to the patient’s world. Mattingly and Fleming,23 in their phenomenological work in clinical reasoning among occupational therapists, described 3 modes of reasoning: procedural, interactive, and conditional. Procedural reasoning represents the typical hypotheticodeductive approach of cue identification, hypothesis generation, and evaluation. Interactive reasoning is the reasoning that occurs during the encounter between the patient and therapist as the therapist works to better understand the patient. Conditional reasoning is a multidimensional process that involves the therapist’s reflection upon the clinical encounter from both procedural and interactive views. We found little evidence among our experts of a hypothetico-deductive approach in reasoning, but our experts did demonstrate centering on the patient, and a reflective process would appear to be consistent with a conditional reasoning process. Higgs and Jones43 argued that the key elements of clinical reasoning are the use of knowledge, the act of thinking (cognition), and the process of metacognition 40 . Jensen et al (monitoring one’s thinking or reflection). In their interpretation of clinical reasoning, these core elements occur throughout the reasoning process. In our study, reflection was a critical element for our experts and the means for their continued learning and development of craft knowledge from their experience. Movement: Central to Practice Examination and evaluation of movement played a central role in the clinical practice of these therapists. The therapists displayed manual and observational skills aimed at the assessment of patients’ functional movement. This assessment of movement dysfunction through palpation, observation, or guiding the patient’s body movement was an important aspect of the examination process across clinical specialties. The manual skills of the therapist appeared to be a well-practiced, almost “unconscious” part of their work, as their attention was often focused on dialogue with the patient or family as they worked. Later, when therapists were interviewed while watching videotapes of themselves with the patient, they were able to describe in detail exactly what they were doing with their own bodies, what they felt with their hands, and their rationale for facilitating patient movement. Sometimes, they expressed surprise at how much they were doing with their hands and bodies while their attention was clearly directed elsewhere. Facilitation of the patient’s movement or motor performance was a critical part of prescribed exercise and home programs. Exercise programs were then directly linked to the patient’s function at home or work. Finally, these therapists used touch as a powerful communication tool to guide, stabilize, reassure, and praise their patients. The profession has had a long debate about whether movement dysfunction is the unique aspect of the “discipline of physical therapy.”44 – 46 It appears that in clinical practice, expert therapists demonstrate persistent, skillful manual and observational abilities centered on functional movement specific to the individual patient’s life needs. Virtues Our peer-designated experts had a strong inner drive to succeed and continue to learn. In addition, they were intellectually challenged by patients’ problems, had the patients’ best interests in mind, and sought to solve the problems, not judge the patients. We argue here that these attributes are evidence of professional virtues.47 Brockett defined professional virtues as “those characteristics that contribute to trustworthy relationships between. . .therapists, their clients, colleagues, employers, and the public. Examples are integrity, an attitude of respect for other persons, and a willingness to put client interests ahead of self-interest.”48(p201) Benner et al2 Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў asserted that ethical expertise is one dimension found in professions where there are caring practices that include recognition and respect for the other, mutual realization, and protection of vulnerability. Purtilo49,50 contended that, although ethical duties and rights provide the conceptual tools for recognizing and resolving problems in everyday physical therapy practice, the development of moral character assists in difficult, complex situations. Furthermore, the larger framework of mutual respect and care needs to be considered. Our therapists shared common character traits as committed and caring professionals who hold ultimate respect for their patients. Benner described the moral dimension of clinical judgment well: “Clinical judgment cannot be sound without knowing the patient’s/family’s situation and moral concerns. The moral perception cannot be astute without knowing and caring about the patient/family.”51(p49) Conception of Practice: Implications for the Profession At the heart of our theoretical model of expert practice is the therapist’s conception of physical therapy practice. The conception of practice is not a single entity. The elements of the 4 dimensions of expertise (ie, knowledge, reasoning, movement skills, and virtuous behavior) overlap and interplay to form this conception. Key elements in the conception of practice include the role of practical knowledge learned through listening to patients and reflective practice, core beliefs about patient-centered evaluation and treatment, collaborating with and teaching patients and families to maximize function, skillful movement assessment through observation and manual skills, and shared commitment of mutual respect and care. If expertise in physical therapy is some combination of knowledge, judgment, movement, and virtue, can clinical practice and education be designed in a manner to address these multiple dimensions of professional competence? Our practice environments could find mechanisms to provide the scarcest resource of all: time. Physical therapists need time with their patients, time with their colleagues, time for reflection, and time to return to the literature if they are to develop the knowledge-inpractice that results in becoming better and wiser clinicians. We suggest that managers consider placing a high value on time for learning as an integral part of practice. Just as physicians are expected to participate in rounds, to review the literature, and to serve as clinical mentors, physical therapists could also have these expectations. Our therapists demonstrated complex clinical reasoning skills centered on the patient they were treating but using recall of pertinent information from the “data Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 bank” of previous similar cases. If the physical therapist is seen entirely as a person who performs an initial examination, designs a plan of care, and then turns that patient over to another provider, then we deny that therapist the opportunity to learn about the ongoing changes that occur as a result of the clinical or teaching interventions provided. Movement was also intimately interwoven with clinical reasoning as our therapists used data gathered from close observation and hands-on care of patients as a primary source of knowledge. Continuity of care provides the information base for clinical reasoning—learning from one patient to apply to the next patient. One of the most obvious things we learned from studying our therapists was their strong sense of commitment to their patients and families and their continued personal quest for excellence. In addition, these therapists are intrigued and challenged by patient care—they love their work! We need to identify these expert clinicians in our profession and encourage them to become the role models and mentors for the next generation. The stories of these expert clinicians provide a rich stimulus for clinicians and educators to contemplate as they plan for their own professional development or for the development of students. Our work suggests that there is a need for education to be rooted in practice, taught around patient care by people who understand both patient care and the relevance of scientific knowledge for the advancement of patient care and who value the importance of lifelong learning and engage in reflective practice that results in deliberative, moral action. Practice by expert therapists also suggests the following strategies be considered when teaching students: (1) teaching students to value the patient as well as the clinical instructor as a source of knowledge, (2) carefully listening to patients and understanding the meanings patients hold about health and illness, and (3) developing not only cognitive skills, but also the ability to keenly observe and skillfully use one’s hands and body to facilitate patients’ functional movements. Development of these manual, practical skills will require focused, intense practice as well as continuity of practice. In addition, students need to learn reflectionin-action in every venue and to witness clinical instructors “thinking out loud” as they identify and solve patient problems. Finally, students must learn to seek out and value a wide spectrum of sources of knowledge and enjoy the challenge of embedding this new knowledge in everyday practice. One of the most important physical therapy interventions valued by our experts was that of teaching patients and families about their clinical problems and how to Jensen et al . 41 care for themselves. For many of the experts, the success of the total patient encounter rested on their abilities to successfully teach the patient and the family. Thus, students need knowledge and skills of effective teaching and learning as well as to develop an understanding of the difficult process of changing health behaviors. Students should be aware that a nonjudgmental approach to patients is likely to enhance their effectiveness and that collaboration with the patient is essential in designing treatment programs. Finally, our novice colleagues need to be supported for exhibiting the virtues of caring, compassion, and commitment. They need to witness practitioners who demonstrate these virtues in practice (eg, by assuming powerful patient advocacy roles) and be challenged to emulate these virtues. Future Research Our theoretical model of expert practice in physical therapy has been developed from our previous research, existing theory on expertise, and the data from our sample of therapists. The investigation involved multiple researchers, multiple settings, and different clinical specialties. Although this diversity allowed numerous opportunities for conceptualization based on triangulation of evidence, there is a need for more in-depth investigations in targeted areas. Further work is needed to expand and refine the model across expert clinicians in other clinical specialty areas. We also suspect there are many therapists who demonstrate the dimensions of expert practice who do not fit neatly into one specific clinical specialty area or who do not necessarily reflect the same criteria we used to select this sample. We need to study representative samples of these therapists both to determine the relevance of the 4 dimensions to their style of practice and to gain a sense of where and under what circumstances the experts in our profession are practicing. Research also is needed to determine whether experts have more effective patient care outcomes than other therapists and what factors may contribute to those outcomes. Finally, research is needed on the development of clinical expertise. Why do some therapists continue to develop into expert clinicians, while other lapse into mediocrity? Conclusion We have outlined 4 major dimensions of expert practice in physical therapy: knowledge, clinical reasoning, movement, and virtues. Each dimension was described using supporting evidence from 4 composite case studies in 4 specialty areas of practice: geriatrics, neurology, orthopedics, and pediatrics. The identification of these dimensions expands the traditional areas of expertise, knowledge, and clinical reasoning and includes areas specific to the physical therapists in our sample, the central role of movement, and evidence of strong vir- 42 . Jensen et al tues. Central to understanding the physical therapists we studied was understanding their conception of clinical practice. Their beliefs about what it means to be a therapist, their goals for patients, and their beliefs about the role of physical therapy in health care were at the center of their practice. Acknowledgments We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation, sacrifice of time, and reflective comments and responses from our sample of clinicians. We also are indebted to their patients who shared their time and allowed their treatment sessions to be videotaped. References 1 Ericsson KA, ed. The Road to Excellence. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1996:1–50. 2 Benner P, Tanner CA, Chesla CA. Expertise in Nursing Practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co Inc; 1996. 3 Sternberg RJ, Horvath JA. A prototype view of expert teaching. Educational Researcher. 1995;24:9 –17. 4 Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. Alexandria, Va: American Physical Therapy Association; 1997. 5 Eddy D. Clinical Decision Making: From Theory to Practice. Boston, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Publishers Inc; 1996. 6 Newell A, Simon HA. Human Problem Solving. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice-Hall; 1972. 7 Holyoak D. Symbolic connectionism: toward third-generation theories of expertise. In: Ericsson KA, Smith J, eds. Toward a General Theory of Expertise. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1991:301–335. 8 Elstein AS, Shulman LS, Sprafka SA. Medical Problem Solving: An Analysis of Clinical Reasoning. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1978. 9 Neufeld V, Norman GR, Feightner JW, Barrows HS. Clinical problem-solving by medical students: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Med Educ. 1981;15:315–322. 10 Barrows HS, Tamblyn RM. Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co Inc; 1980. 11 Schmidt HG, Norman GR, Boshuizen HP. A cognitive perspective on medical expertise: theory and implication. Acad Med. 1990;65:611– 621. 12 Elstein AS, Shulman LS, Sprafka SA. Medical problem solving: a ten-year retrospective. Eval Health Prof. 1990;13:5–36. 13 Patel VL, Kaufman D, Magder S. The acquisition of medical expertise in complex environments. In: Ericsson KA, ed. The Road to Excellence. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1996: 127–165. 14 Ericsson KA, Smith J, eds. Toward a General Theory of Expertise. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1991. 15 Payton OD. Clinical reasoning process in physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1985;65:924 –928. 16 Rivett DA, Higgs J. Hypothesis generation in the clinical reasoning behavior of manual therapists. Journal of Physical Therapy Education. 1997;11(1):40 – 45. 17 May BJ, Dennis JK. Expert decision making in physical therapy: a survey of practitioners. Phys Ther. 1991;71:190 –202. Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў 18 Embrey DG, Guthrie MR, White OR, Dietz J. Clinical decision making by experienced and inexperienced pediatric physical therapists for children with diplegic cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 1996;76:20 –33. 35 Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1990. 19 Jensen GM, Shepard KF, Hack LM. The novice versus the experienced clinician: insights into the work of the physical therapist. Phys Ther. 1990;70:314 –323. 36 Robrecht LC. Grounded theory: evolving methods. Qualitative Health Research. 1995;5:169 –177. 20 Jensen GM, Shepard KF, Gwyer J, Hack LM. Attribute dimensions that distinguish master and novice physical therapy clinicians in orthopedic settings. Phys Ther. 1992;72:711–722. 21 Higgs J, Titchen A. The nature, generation and verification of knowledge. Physiotherapy. 1995;81:521–530. 22 Robertson VJ. Research and the cumulation of knowledge in Physical Therapy. Phys Ther. 1995;75:223–232. 23 Mattingly C, Fleming MH. Clinical Reasoning. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis Co; 1994. 24 Schon D. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983. 25 Chenitz WC, Swanson JM. From Practice to Grounded Theory. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co Inc; 1986. 26 Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1994:271–285. 27 Morse JM. Qualitative Nursing Research: A Contemporary Dialogue. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen Publishers Inc; 1989. 28 Shepard KF, Hack LM, Gwyer J, Jensen GM. Grounded theory approach to describing the phenomenon of expert practice in physical therapy. Qualitative Health Research. 1999;9:746 –758. 37 Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1985:289 –331. 38 Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1997:193–218. 39 Jensen GM. Qualitative methods in physical therapy research: a form of disciplined inquiry. Phys Ther. 1989;69:492–500. 40 Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Hack LM, Shepard KF. Expertise in Physical Therapy Practice. Newton, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999. 41 Eraut M. Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. Washington, DC: Falmer Press; 1994. 42 Harris I. New expectations for professional competence. In: Curry L, Wergin J, and associates, eds. Educating Professionals: Responding to New Expectations for Competence and Accountability. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Inc Publishers; 1993:17–52. 43 Higgs J, Jones M, eds. Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions. Boston, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995:3–23. 44 Hislop HJ. Tenth Mary McMillan Lecture: The not-so-impossible dream. Phys Ther. 1975;55:1069 –1080. 45 Rothstein JM. Pathokinesiology: a name for our times? Phys Ther. 1986;66:364 –365. 46 Winstein CJ, Knecht HG. Movement science and its relevance to physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1990;70:759 –762. 29 Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co Inc; 1982. 47 Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. The Virtues in Medical Practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993. 30 Yin R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1989. 48 Brockett M. Ethics, moral reasoning, and professional virtue in occupational therapy education. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996;63:197–205. 31 Miles M, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1992. 32 Martin C, Siosteen A, Shepard KF. The professional development of expert physical therapists in four areas of clinical practice. Nordic Physiotherapy. 1995;1:4 –11. 33 Benner P, Wrubel J. The Primacy of Caring: Stress and Coping in Health and Illness. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co Inc; 1989:1–26. 49 Purtilo RB. Professional responsibility in physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 1986;72:579 –583. 50 Purtilo RB. Ethical Dimensions in the Health Professions. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1998. 51 Benner P. Caring as a way of knowing and not knowing. In: Phillips S, Benner P, eds. A Crisis in Care. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 1995:42– 62. 34 Morse J. Emerging from the data: the cognitive processes of analysis in qualitative inquiry. In: Morse J, ed. Critical Issues in Qualitative Research Methods. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications Inc; 1994:23– 43. Physical Therapy . Volume 80 . Number 1 . January 2000 Jensen et al . 43