urban water services Community participation in

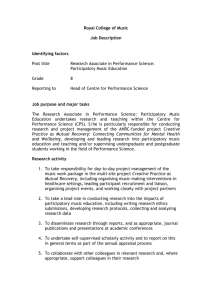

advertisement