GAE 2012 Dynamics of Global Accountancy Education

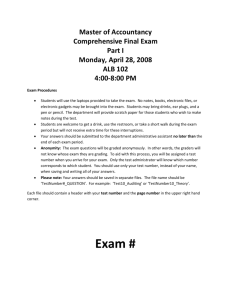

advertisement