SAMPLE

1. ADDING Value1

Pankaj Ghemawat

The introduction explains that international or global strategy requires distinctive content

because the state of the world is one of semiglobalization, in which the differences

between countries continue to be substantial. Global strategy requires dealing with this

complex reality, in which neither the interactions between countries nor the differences

that continue to divide them can be ignored, in order to create and claim more value

across borders than a collection of single-country enterprises could do on their own. In

other words, the fundamental objective of global strategy is to account for differences so

as to produce a whole that exceeds the sum of its national parts by as large a measure as

possible.

This section introduces the ADDING value scorecard and uses it to identify and calibrate

the levers through which global strategy can create (or destroy) value, and to assess

alternative strategy options. Some of the levers are likely to be familiar from singlecountry strategy but others are new or applied in rather different ways, as discussed in

this section. The next section, on the CAGE distance framework, identifies and explores

the effects of cross-country differences of various sorts on international economic

interactions. Taken together, sections 1 and 2 supply the basic tools necessary to pursue

the objective articulated in the introduction: applying a firm-centric, value-focused

perspective to a substrate of cross-country differences.

The ADDING Value Scorecard

The late C. Northcote Parkinson noted in one of his less famous laws that businesspeople

tend to do detailed cost-benefit analyses of relatively small decisions but simply throw up

their hands and surrender to animal spirits when making large ones.2 There is a sense in

some quarters that global strategic moves are so complex and so subject to uncertainty

that they essentially become matters of faith. The ADDING value scorecard presented

here is intended as an antidote to this kind of thinking.3 ADDING is an acronym that

parses the assessment of international business strategy into the individual levers via

which value is created, each of which is amenable to careful (and in many cases

quantitative) analysis: Adding volume, Decreasing costs, Differentiating or increasing

willingness to pay, Improving industry attractiveness, Normalizing risks, and Generating

knowledge and other resources.

The components of the ADDING value scorecard are meant to be commensurable, and to

add up to determine overall value addition or subtraction. The first four components

should be familiar from single-country strategy: adding volume (or, with a more dynamic

frame, growth), decreasing costs, differentiating or increasing willingness to pay, and

increasing industry attractiveness. They reflect what might be called the fundamental

equation of business strategy:

1

Your margin = industry margin + your competitive advantage

Michael Porter’s famous five-forces framework for the structural analysis of industries

has explored the strategic determinants of industry profitability (the first term on the right

side of the equation).4 Porter and other strategists, notably Adam Brandenburger and Gus

Stuart, have probed the determinants of competitive advantage (the second term on the

right side of the equation), and emphasized characterizing it in terms of willingness to

pay and (opportunity) costs:5

Your competitive advantage = [willingness to pay – cost] for your company –

[willingness to pay – cost] for your competitor = your relative willingness to pay

– your relative cost.

In other words, in single-country strategy a company is said to have created competitive

advantage over its rivals if it has driven a wider wedge between willingness to pay and

cost than its competitors have done.

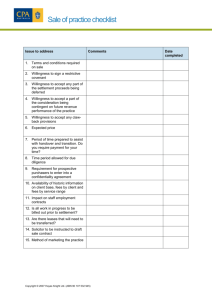

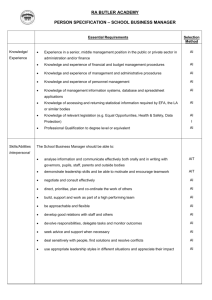

The final two components of ADDING value—normalizing risk and generation of

knowledge and other resources—reflect the large differences that persist across countries.

Thus, they are customary add-ons in global strategy. The relationships among the

components are summarized in exhibit 1-1.

Exhibit 1-1. The Components of the ADDING Value Scorecard

Volume

Economic

Value

Competitive

Advantage

• Costs

• Differentiation

Margin

+

Uncertainty/

Risk

Industry

Attractiveness/

Leverage

Knowledge/

Resources

Applying the ADDING Value Scorecard

When applying the ADDING value scorecard, it is useful to begin by quickly thinking

through the list of value components and brainstorming about the ways that economic

value could be increased or decreased under each heading. Then, go back and review the

lists to figure out elements that might still be added and to begin to think through the

impact of each. It is generally very helpful to quantify numerically (at least to a rough

2

order of magnitude) those elements that are amenable to quantification. For what cannot

be quantified, note the direction of the impact and your general assessment of its

magnitude (e.g., “++” for a large positive impact or “–” for a small negative one). Then,

add up the quantified impacts and weigh them against the collective impact of the

elements that could not be quantified. While complete quantification is rarely possible,

partial quantification makes clear how much positive or negative impact the remaining

elements must have to sway the decision, improving the ultimate conclusion.

The following sections offer specific suggestions to consider when analyzing each

component of the ADDING value scorecard.

Adding Volume or Growth

Assess the economic profitability of incremental volume—that is, determine accounting

profits minus capital recovery costs. While this may seem like an obvious requirement

for a value-focused analysis, it is worth noting that research indicates many large

companies maintain significant country operations that generate negative economic

returns over long periods of time.

Understand the level at which economies of scale or scope really matter and

calibrate their magnitudes. While it is often assumed in global strategy that global scale

is what counts, there are many other possibilities: national scale, plant scale, share of

customer wallet, and so on. Economies of scale or scope should ideally be calibrated

rather than just identified since their strength varies substantially across industries and

can be dependent on other aspects of a firm’s strategy.

Assess the other effects of incremental volume. The previous point focused on

economies of scale, particularly on the cost side. But incremental volume can also have

other effects—not all of them positive—on a company’s economics. If a key input is in

short supply, for instance, additional volume may raise rather than lower costs.

Decreasing Costs

Unbundle cost and price effects. Expressing costs as a percentage of revenues can

obscure the true effects of cross-border moves on a company’s cost structure. Instead,

think about other ways to normalize costs. In some cases, it is useful to analyze cost per

unit of output to clearly separate volume and price effects. In other cases, it can also be

useful to normalize cost per unit of a key input, such as capital or labor.

Unbundle costs into subcategories. Cross-border moves typically have different

impacts on various line items within a company’s cost structure, so it is important to

analyze each of the major cost components separately. Don’t forget to consider capital

costs in addition to operating costs. Fixed and variable costs also represent another key

distinction, particularly for purposes such as breakeven analyses.

Consider cost increases as well as decreases. This point, already made briefly, is

worth reiterating. Consider, for example, takeover premiums and transaction costs

involved with cross-border mergers. Remember that increases in complexity may impact

not only production costs but also selling, general, and administrative costs.

3

Look at cost drivers other than scale and scope. Strategists know that there are

many other potential drivers of costs beyond scale and scope: location (particularly

important in a cross-border context), capacity utilization, vertical integration, timing (e.g.,

early-mover advantages), functional policies, and institutional factors (e.g., unionization

and governmental regulations such as tariffs).

Relate the potential for absolute cost reductions to labor intensity or the intensity

of other inputs. Labor is just one avenue for potential economic arbitrage; capital, natural

resources and specialized inputs represent others. Arbitrage opportunities will be

elaborated on in section 5.

Differentiating or Increasing Willingness to Pay

Relate the potential for differentiation to R&D-to-sales and advertising-to-sales ratios for

your industry. These ratios are the most robust markers of multinational presence, which

is why product differentiation is considered key to strategies that seek to tap scale

economies by expanding across borders. R&D expenditures equal to 0.9 percent of sales

revenues define the bottom quartile of U.S. manufacturing, 2.0 percent of revenues the

median, and 3.5 percent of revenues the top quartile. The corresponding cutoff points for

advertising-to-sales ratios are 0.8 percent, 1.7 percent, and 3.5 percent. Compare a

company’s and industry’s ratios versus these benchmarks to quickly check the scope for

differentiation that it is likely to afford.

Focus on willingness to pay rather than prices paid. There are at least two

problems with using price as a proxy for the benefits for which buyers are willing to pay.

First, prices mix a number of other influences related to industry attractiveness and

bargaining power. Second, a focus on willingness to pay encourages envisioning things

as they might be rather than as they actually are—supporting development of a more

creative range of strategy options.

Think through how globality affects willingness to pay. There are some cases of

cross-border presence directly boosting willingness to pay—for instance, for individual

customers who travel internationally or want to belong to a global community, or for

companies that are themselves global and value consistent products and services across

locations. But especially in consumer businesses, cross-border appeal is more often

rooted in specific country-of-origin advantages (e.g., French wine).

Analyze how cross-border heterogeneity in preferences affects willingness to pay

for the products offered. In the next section, the CAGE distance framework will be

introduced to help discern more precisely the cross-country differences that firms must

account for in their strategies. For now, lets just say that while differences sometimes

support country-of-origin advantages, they more often reduce willingness to pay for

foreign products or services. Even subtle differences can render a product that works well

in one country inferior or entirely unsalable in another.

Segment the market appropriately. Segmentation obviously picks up on

differences in willingness to pay (and, sometimes, differences in costs). Typically, the

number of segments to be considered increases with diversity in customer needs and ease

in customizing the firm’s products or services. The greater diversity companies face

operating internationally increases the benefits of market segmentation.

4

Improving Industry Attractiveness or Bargaining Power

Account for international differences in industry profitability. Substantial differences in

average firm profitability across countries, even within the same industry, are often

overlooked. Be sure to understand these patterns when assessing markets.

Understand concentration dynamics in your industry. Contrary to what many

assume, global integration does not necessarily increase global concentration.6 Analyze

the concentration dynamics of an industry at the global, regional, and country levels for a

basic check of the current competitive context and how it is likely to evolve.

Look broadly at other changes in industry structure. Consider how the factors in

Michael Porter’s five-forces framework are changing. For example, are shifts in sales or

production to emerging markets changing the bargaining power of buyers or suppliers?

Think through how you can de-escalate or escalate the degree of rivalry. Conduct

detailed structural and competitor analysis to figure out competitors’ likely responses to

strategic moves.

Recognize the implications of your actions for rivals’ costs or willingness to pay

for their products. Raising rivals’ costs or reducing their willingness to pay can do as

much for a company’s profits as improving its own position in absolute terms.

Attend to regulatory, or nonmarket, restraints—and ethics. Behavior aimed at

building up bargaining power is always a sensitive matter, and the legal status of the

strategies listed under the preceding two headings, in particular, varies across countries.

Be careful of the legal and ethical considerations that may arise around these types of

strategies.

Normalizing Risk

Characterize the extent of key sources of risk in a business (capital intensity, demand

volatility, etc.). A useful way of summarizing risks is in terms of the learn-to-burn rate: a

ratio that looks at how quickly information resolving key uncertainties comes in versus

the rate at which money is (irreversibly) being spent.

Assess how much cross-border operations reduce risk—or increase it.

International operations can provide geographic risk pooling, but can also create new

sources of risk. For example, a company reliant on cross-border supply chains faces very

different risks from one with more localized production.

Recognize any benefits that might accrue from increasing risk. Risk can, given

optionality, be valuable for the same reason that financial options are more valuable in

the presence of greater (price) volatility. Thus, some multinationals think of emerging

markets as strategic options rather than just as risk traps.

Consider multiple modes of managing exposure to risk or exploitation of

optionality. For example, a company may enter a foreign market with a fully owned

greenfield operation, make an acquisition, work with a joint venture partner, or simply

export there. Or, given widely diversified shareholders, it may make more sense to rely

on shareholders to eliminate industry-specific risks and, given that possibility, to discount

them in formulating company strategy.

5

Generating Knowledge—and Other Resources or Capabilities

Assess to what extent knowledge is location-specific versus mobile and the implications

for knowledge transfer. Cross-country differences may require explicit attention to

knowledge decontextualization and recontextualization. Otherwise, knowledge transfer

can make matters worse rather than better.

Consider multiple modes of managing the generation and diffusion of knowledge.

In addition to formal mechanisms, don’t forget about informal ways that knowledge

diffuses across borders: through personal interactions; working with buyers, suppliers, or

consultants; open innovation; imitation; contracting for use of knowledge; and so forth.

Think of other resources in similar terms. Knowledge transfer is sometimes

thought of purely technically—a tendency reinforced by the ease with which patents can

be counted. But other kinds of information, such as business-model or management

innovations, can also be transferred across borders. Even more generally, other

organizational resources/capabilities with broad effects might be analyzed in similar ways.

Avoid double-counting. While it is important to avoid double-counting in all of

the components of the scorecard, be aware that it is particularly likely to arise here. If you

have already accounted for the effects of generating (or depleting) a resource on cost,

willingness to pay, and so on—which is generally recommended—do not repeat them

here.

Conclusion

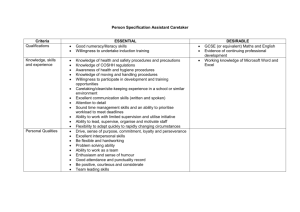

The ADDING value scorecard parses cross-border value addition (or subtraction) in

manageable, commensurable components to facilitate robust and meaningful analysis of

international strategies. By applying the scorecard, one can avoid typical strategic errors

such as “sizeism” that may result, for example, from focusing on narrow metrics like the

percentage of a company’s revenues earned outside its home country. The scorecard may

also be used outside-in to assess a competitor’s global strategy and to try to predict its

future moves. More broadly, it is also useful to think about the sustainability of each of

the sources of value addition or subtraction to add a dynamic perspective to the analysis.

Exhibit 1-2 summarizes the guidelines presented here for applying the ADDING value

scorecard.

6

Exhibit 1-2 Applying the ADDING Value Scorecard

Components

of Value

Adding Volume

/ Growth

Guidelines

Decreasing

Costs

Differentiating /

Increasing

Willingness-toPay

Improving

Industry

Attractiveness /

Bargaining

Power

Normalizing (or

Optimizing)

Risk

Generating

Knowledge (and

other Resources

or Capabilities)

Look at the true economic profitability of incremental volume (taking into

account cost of capital)

Probe the level at which additional volume yields economics of scale (or

scope): globally, nationally, at the plant or customer level, etc.

Calibrate the strength of scale effects (slope, percentage of costs/revenues

affected)

Assess the other effects of volume

Unbundle price effects and cost effects

Unbundle costs into subcategories

Consider cost increases (e.g., due to complexity, adaptation, etc.) as well as

decreases and net them out

Look at cost drivers other than scale/scope

Look at labor cost/sales ratios for your industry (or company)

Look at R&D/sales and advertising/sales ratios for your industry

Focus on willingness to pay rather than prices paid

Think through how globality affects willingness to pay

Analyze, in particular, how cross-country (CAGE) heterogeneity in

preferences affects willingness to pay for products on offer

Segment the market appropriately

Account for international differences in industry profitability

Understand the structural dynamics of your industry

Look broadly at the impact of trends and moves in changing important

elements of industry structure

In particular, think through how you can deescalate/escalate rivalry

Recognize the implications of what you do for rivals’ costs or willingness to

pay for their products (worsening their positions can do as much for added

value as improving your own)

Attend to regulatory/nonmarket restraints—and ethics

Characterize the extent and key sources of risk in your business (capital

intensity, other irreversibility correlates, demand volatility, etc.)

Assess how much cross border operations reduce or increase risk

Recognize any benefits that might accrue from increasing risk

Consider multiple modes of managing risk or optionality

Assess how location-specific versus mobile knowledge is, and the implications

for knowledge transfer

Consider multiple modes of generating (and diffusing) knowledge

Think of other resources/capabilities in similar terms

Avoid double-counting

Working through the ADDING value scorecard also helps surface some of the

opportunities and challenges that result from semiglobalization and the reality of

persistent cross-country differences. The CAGE distance framework is introduced in

section 2 to sharpen the analysis of such differences.

7

1 Pankaj Ghemawat And Jordan I. Siegel, “Cases on Redefining Global Strategy” , (Harvard

Business Review Press, 2011):1-10

2

C. Northcote Parkinson, Parkinson’s Law and Other Studies in Administration (Boston:

Houghton Mifflin, 1956).

3

For more detail about the ADDING value scorecard and its application, see chapter 3 of Pankaj

Ghemawat, Redefining Global Strategy (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007); and for a general

discussion of value creation and capture in a single-country context, see Pankaj Ghemawat, Strategy and

the Business Landscape, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009).

4

Michael E. Porter, Competitive Strategy (New York: Free Press, 1980).

5

Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage (New York: Free Press, 1985); and Adam M.

Brandenburger and Harborne W. Stuart Jr., “Value-Based Business Strategy,” Journal of Economics &

Management Strategy 5, no. 1 (1996): 5–24.

6

Pankaj Ghemawat and Fariborz Ghadar, “Global Integration ≠ Global Concentration,” Industrial

and Corporate Change, August 2006, especially 597–603.

8