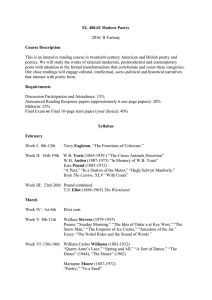

Ball State University

advertisement

Ball State University

"Eliot's Theory of the Three Voices of Poetry as

Illuminated by Its Application to The Waste Land"

Julia Ballard

ID 499

September 1, 1969

,~.....

(

---~~'h'

i

t

~

....

,.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Frances Rippy, under

whose direction this paper was written, for

her valuable assistance and encouragement.

ii

Eliot's Theory of the Three Voices of Poetry as

Illuminated by Its Application to The Waste Land

T.S. Eliot delivered a lecture in 1953 in which he sought to explain

his concept of the three voices of poetry.l

In summing up his comments,':he

asked his listeners to test his assertions as they read poetry.

This paper

is an attempt to employ Eliot's suggestion and to test his principle of the

three voices of poetry in an analysis of Eliot's own poem.

The Waste Land.

Eliot defined the three voices of poetry in the following manner:

The first is the voice of the poet talking to himself -- or to

nobody. The second is the voice of the poet addressing an audience,

whether large or small. The third is the voice of the poet when he

attempts to create a dramatic character speaking in verse; when he

is saying, not what he would say in his own person, but only what he

can say within the limits of one imaginary character addressing another

imaginary character. 2

The poet further stated in his lecture that the reader of poetry

who complains that a poet is obscure or speaks only to a limited circle

1

The Three Voices of Poetry (New York:

Press, 1954).

2Ibid ., pp. 6-7

Cambridge University

2

of initiates must keep in mind that the poet endeavors to put into words

that which cannot be'. said in any other way.

The language used, Eliot

asserts, "may be worth the trouble of learning.,,3

Eliot offers his,

explanation of the three voices of poetry as one key to learning the

poet's language.

Readers of The Waste Land have

con~nded

that the poet is far too

difficult and, to use Eliot's term, far too obscure.

If Eliot was

being accurate in his lecture, he has written the poem in the only

way in which he could

in his own language.

When The Waste Land

is read with a knowledge of Eliot's theory of the poem are brought

into. focus.

An analysis based upon this theory yields a greater

insight into what the poet was striving to communicate.

In an article dealing with Eliot's lecture, Delmore

Schwartz wrote:

Whatever Mr. Eliot's purpose may be • .

he provides a classification of the voices

Jf poetry which has an immediate relevance

to any attempt to characterize his poetry

as a whole • • • . what is in question here

is not this classification as true of all

kinds and varieties of poetry, but only

its relationship to the poetry which

Eliot himself has written. 4

0

From this point in his article, Schwartz proceeds to express

his opinion that the reader who seeks to read Eliot's poetry with

a knowledge of the theory of the three poetic voices

3

Ibid., p. 38·,.

4"T.S. Eliot's Vo:..,~e and His Voices," Poetry, LXXXV

(January, 1955), 232.

of each respective voice can be catalogued, Qnd Eliot's

metho~

of blending all threo voices an he constructed

~ecornes

readily apparent.

--------_._--_.

t~e

poen

I.

THE FIRST VOICE

The Poet Talking to 5imself -- or Nobody

Eliot at-terC'pt.ec1 to el2..00rate

the fi:::-st uoice ]-,y

rE'fe~ri '-'0

to

:::l

U,jOl1

his c1 efir'.i -::io,[ of

lectu~(~

enti tIer'. ProhlcIllc

der Lvrick delivercc' by t 1,c GerD2.I' "oct, Got·t:::.'::-ie-' Berl'..

There

:LS

first

Te,:.ou~,:--c.cs

of t.he

et 1~" ::~ r.~cf

Cf()J~"2 i"CJ.

P.017

1,?OJ:"·(~.0;

]~;:..C:.

~'-)11t

fOl.1T":(

~'"'C

+::·. . e

il)e_;:--~:

-:rL

-t Fj 0

or~

3.r'~} ,

~:,701~C~.r-y

z -t i

,::;-:~-

.~~ r~

;-'ot "\,

~.'IOT-r\.S;

0

t '., OJ":

tl"'t~

i"":-'c.

~ "1

("1

~-

l1~'

i

\7;"'1-'-1: l:,"'or-'::

C:;.~·-: -'.01~_

or

~~'~orc

C2~-':--"; T,l "[7

':-10-;~,

c~-:

.. ~.c

~_(:;_0'1-~:i .;:-~'.:--

29.

5

_,·r,

;

IJ~~·'.11~'U .::~r':(~ ,

cO;~";I.G::l',--:.

0r:.o·~~_j~O!· ,

i i-: is :.. . t~.}_l

tlc~CC2. t.~_~.7e

t: lie

Z'"' n.c~,

.r;oetf~

i? r 0

"'-.

j-~O~l

e;~;'J:'-\TO

-h

f"2.~

~-j

e

Tl.tl s

'ir.J2~'i.tr:

-:.::-.j.,~

~-~c

t

_r-:.

i ~c'"

t:~c

h" 'C.'

..""!

-:~-;~tj_}_

~0;-1.~-::':--:~O

;:.0

~i."-d:-::i 1

6

The opening lines of The Waste Land,

April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with sprinq rain lO

are a perfect example of a first-voice attempt to obt0in

suc~

relief for Eliot.

first-voice poetry to

CJ.

sort. of "e~:orcisr;," of

ti'9

('1-?Bon. l1

in '-,is poetry.

too

0:':

1:0

-'C'

cO"--

··"\n····

"r:"':;":'"l ....

--

~. l

• . i.

_ ~

1

_

•

I

re?e;--~t:'G'.::

1)() c:r~

l.cl I"':

e Co~-· nl. etc Po e'-'.':' ;::'1c' p]. 2. '7 [~ c.' c\} ''':'"0 r 1- : :;T::- ::-:-:0'-' rt ,

19j2)~, If: 1_.,1

S1.l1·'sequ~-·\·t c-,--=,:'o,:-c:cc:::: J: o 1i-o;.

in c J ue cc' ~,~~rc~- t L". ct i c ;::;.11 \':i t~;.i~~ t"', e t: C~:~t

,: :-: :rc:

rp'j

B::-2ce ~!J

=:0.;-

o ~_~

8i:1 ,

t"1,'l

C·~~Z-1.~·.7n

i:7

tiC)

fJ':-o:~

":7

tl."'is ec5.itiot).

12 11-~]'

.~J

,.1

_ ',.'• •

7

Ei~J

L""[:liot'§.7 i(~"':',r: 0::: irnJ:)er'3or~~lit:T 2",d ohje;-tivity

in ccr"l:, t"8 '·'ccc.'"'::;ity fo.:- 'i:'-8 ,~uhor(qi!12tior; of feelinr:

to -CliO «~j~,scil)linc~ of 2 religJol1S S:,",st:en:, ~-jis ij~~si.ste!1ce

on trCl,~l,ition, onIer ;::>,;yl finis~'; :!.D e::ecut:i_o'l ('i--,r1 cla;:-ity

,

.

11

' tnetJ_cc:,.,1 to Ro'X::U'tlCJ.s;n.

.,

1")J

In

concept lOP

;;.:rf~ ::' _

antl

1

•

a~~ti-Romantic

Georqe's stateTl:.en":: e::pJ ;:).in3 Eliot' s

t~e

and it also shade light on

poetic comnent.

~oet's

They are, however,

t~e

Eliot's rejection of

personal poetry may

--~(e·t

\<r~!cn

<.',T;l;;

ST)C()_}:

Q~cJ

\'}C

un~erlie

C~F'C

j:ull,

intensely

~~/

c~let~

late,

~·',J.ir

'C01Jj:"

f<.i12r~,

~-·o~_

Ronantic tendencv toward

the fact

~-"('c1c,

~-:;~,:

. . ,. -1.('::1..':;, (::,:~,(~. I

LookL"'Cf i_':to C~'C o'C2o~i=

Oed' u,!6 leer (~.3,::: n~~Or!~ri.\/iT"rr

a~

\V;,C't Eliot bir,self c211s '"meditative

state~ert

Y()l~J~

of first-voice

The openin0 lines are not didactic, narrative,

or animated hy social purpose.

personal

expl2l~atio~

ooer'inC" lines

J

l~~l<?-~J

0::

:~:::-O:'G

,-Ie'!::,

~/!;:l.~;

t>8

s~all

propor-

~~y~_~i~!w::h

0~~~.~(;e~~_,

I could. ,'ot

~!.eit"i~1e~~

:l.o~:"flj_~-"'r:r,

l i re1 -::,

(11.

onlv a

t~at

~::)(}

2i2:~c~c('.

37-i~~).

"J5

_._,

0':-(:'1

-

JP7•

.~~ tOl~C'3~. "con.

--.-------------- ......-_._._--

')

cx~crie~cc

~~ c·"o'-.h>ce

J..e""JJ

,

....

-0'

1",-,-

~hich

Deec·'

e'--']'.._,

nt~.-~

. , ret::--tl'

0.',.". ,",1'_;_+".,,1-.e].(".• ,,16

! l , ;"10"er

,

\ . . n,,'

I·.l.,

<'::' ..""'

'J

'-,

........J

..:;

Ag::lin I

~

_

lir..e 176,

II

L-.

Sweet Thames, run softly till I

end

my sona... , " and lines 182-186,

By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept

Sweet Thames, run softly t i l l I end ny song,

5vmet TIl ame.3, run softly, for I Gneai': T.Ot 10u(1 0'- lor-e.

:'>ut 2t rr{ 1),l.ck ill 2. cold ;~12st I heCl~

The rattle of t~e no~es, ~n~ chuckle snrc0d f~o~ ear to

__ r.. -..-'

.

0';=

~;lio::

I

.....

'-'

r

-_ __._----------_._----_._ _------..

...

16 T • S • Eliot: Tl-.e DC0.ic;n o:~ II-i __s Poe-t:r'l;7 (-:'To,"< :to~:--~::

Scr i:)ner '.::; Son[:, 19,(19),

:'!.

70.

("~=""·-'.~-lcr

o

head,

ete.-eni ty. III 7

Taken

fro~

eastern

an~

western

religious heritage:::, 't:le ,1On;,s have a pu.rticulur' mea.nincr Hi thin

the context of tho poem when it is uncterstood that Eliot

brin~s

East and West together in the first voice and closes the forego ina

section with

2

note of personal despondency for the state of ull

To Carthage then I

o

o

ca~e

Burning burDinr;r lmrninq ~,urninc;

Lord Thou nluckest De out

Lord Thou nluc1~est

(ll.

J 7 ~.,

T'); ,'-

.~.

---------

79.

307-311).

-:lO.iC--~.

,-, '_'-',i--

~"2--'

~_

L!()

'I-O~l

r'"l,::_i_~~--r-0

i!~

f~z:_J.].i'~(~

.-'~()~."j::-"\

"0,'

j. '-,C'"

-,,;-'l

0 _:"'r~ (~:;- '~~

-:--',11'; "'0

·10··.':~

"~"--.l) i~ r;

~Q~'T-'"

Poi c'2seose nol foco ~~~ 01i 2~fi~2

--- - --'l'y-'c,O --:--i~'~ ll"--i ['"-'-";'--0-"

- - 0 0,\,i;:,J10'\,' :-~";211o':--:

i~~~~;l~'~i ~"j:;l~'\-" 1 0_':01.)]: :c~"olie

01. eJ.23-4,33).

The fact

t~nt

these lines are fragmentary and disconnected can

be accounted for hy understancUnq tl'!at "the',.T 2re s',rmDolic of chaos

in the modern world.

They could

~e

spoken in the first voice

only because the fragments are different for e2.el, f:2.n.

first-voice comments are

t~2t

cuI -{:ur;':'cl "trac,i tiol"[ - - a t1: 2.C', i

sense of unity or value.

i

-,r':

,flIich romains for Eliot of

'I: i

Tl~.ese

2.

or-' "if"\ic:h, for him, 1 <:leks 2ry

1 ]

i.n e n. t:}CJ

•

firot-voiCG

is

2!T1.0TlCf

-"~~:r

~o~me~tD.

11 at

·::~-·eE':,

Px:·oT)e::-t,.,r

:-l

2

0=:=

::.-c:l?."tiO!'-·:~3":5.p

0 -;~,j e:-:' -:.:~:

~·~l~·t

c-'_i,SCO\70J:~e('~

J:-21 ,?t.ior [~j~.i;~

2

~1r,(l_

~:;tc·"~:li.s:le,~l

t~:Je

!?oc:t.

11o:-:20'1(J~, t":le rel,:::.tio:ns'lj_p :~2~,r }-'c o:""e

of te-nEJio'- in. \'lr·ic;- t1-~~~ r'-'(l~tc~~i~lG ";'-:-llll cl0fl.i'·:.st: e\"J(":

o '(:~:lG]~ all(~. res i s t (.~:: :. r e,'-l::~\7' re co "i:.~ i 1 i 2. ~t i 0 r;

• ~".;;"'l OTl ;", (;

LEliot7 firs-t e~,!_F'r::i ~,t:G'°t:' is q:i_G'i.' 0:: telsio" i:, Doet.r v ,

i t ~i'G:C~{ rl1t~r:J. ~·1ee~1e(~. ;::~.'J~~Tip.c: - - OJ.~ (J.t le,::::,::,·t :lc!e(·~e(} ]:--e-s(J.~{j_r~ •

•-i:;,,::;l ~;is sti.1tGme~~t of t"i,c:~o1'cepti()n, toc:et!-1er 'i,lit'''~~he

po~ms th2t e8bo(~iecl it, inspirec':' t~-'e J:i_tera:c"

rG'7olutiop.

t~at is sometimes 0iven Eliot's name. 20

G. :Jilsot) Knicr 1,t

I1~Jo

states of Eliot that

pa~:es

a si"1ilar oo.servai:ion \1',en he

poet has been more

d.ee~)}y

hO:t~es-t.

The

results are simultaneously personal in substance anC impersonal

in technique.,,21

Similarly, the "I" of line 1'23 can be interprete<3

an inclusive pc::-ol'oun, 'Jut w1;en

1i~es

w~ic~

follow,

?n

~.- 11~:.S.

it is 2pparently a

Eliot:

(J ~::lU(-)ry-rl(H:"cl' ,

2JII~~1.~j. E}_iot:

:~~c\/.ie\'7,

I.J~·:::'I'\l

cOl!sic~ered

~r::.

i

'9~~

.1'~ ~ ~ (-::; _~

2. ~:. (~.

S~cci~l

in

t1"(~

Derson~l

2S

co-r:!tex-t 0::= t -;c

'

ctatcnent.

It

t i oS t,

rei", e S G\-7;:,~!.ee RevieH,

Issue), 212.

?~ r

11

30:':("~ I..Ji.tc::2r~l Ir:r>:--0r:;(-:'io:·~-, II TI-le S9~72.~:tJe

10 ~r:

3'or'l~t 0.J Is r=11C), 2~) 5-:-----

(J-2"11JuJ~\'?-r,:·~~ ~.~C~l,

17.

1.1;) :

~~~tJ-:::

j_t,

i::~

It i·'-;:,

--oe

j_~~~no""3::1-'~-"'lc

-r:o"~~:·'1·~~_

-:'="o('~l

0"1 ,...

~)2.-".r:C'

r~".~

j .. ~~

t.~~'e

C:C!~lCl't1·'~\:i.·":-~

('~=.:-'-~o'-'n'\'::;-'·~(~

j ,':

'.~.~;-'-~:':('~r".

,~()~ O:_",T'C"<'

.'~-:-'-'"'

+-:- ('l

eli ',,-,

"'0' ,",'2

3ynr12thi::':c,

tl""(~r;:

":0

C~2l!:'i_r'r:

Con'l:~~oJ.,

1''-::;::.<::8,

-t~~a-~:l.~fi0l1::-(:::~

n;:;r~,=iI~·i.:O

:::3<: t7";-' ct

i'

iC1.2ClS;

r"'e(}.eemii)J~~r

s'ln:'}~JO 1 •

surrenCer haG been made, but it still seems a surrcnr:ler

to death, and the ,possibility

of rebirth is stiP, \,rithout

-??

..

substance or outllne.--

}"')a.s

J)eCJ.1

2

The figure fishing upon the shore is also regarded as a

first Derson poetic comment by critic Helen Gardner:

we return to the arid plain and the single figure

on the s]lore fis':.ing.

Tile Bridgc over Hhich the CYO\vd flovled

is falling dOHn.

There CODe to ,',"'i:-:ci three phrases: a p.~1.Y2,Se

expressina surrender to ."poi-·", (1-,.:..(:~. terro:':."', ;1 J)~lJ~2.f3E:! ·~:ec12_ril1.r­

E!r\C~_ 2 l")"').r:.!.se i:~~!.?t SU(fO'(~sts c.:. t.otc'.l

lorqi~~ for freedom,

c1es'ci tutio:n

::-';;-S=Y:T1CP,tS

•.• ...J

',;i S (:1 0-: ,the poet 1e2""0,, 1.','

i,r.

Roy-.:~~·ti~''''

I':

"~'::'

--------_._-') ')

,

"p~,

~

"

)'='-'10

--'-"------- ..

__ _._---------- -----..

E9-90.

.:~:~-t

O~': 1).1.3 •.~~~li,ot

('~'~\"'r

:{or':: F,.J.?

r)11.~-.to~~

'~O.,

19c;O) ,

96.,

~""«'-'"'' .., , - ' - - - - - - - , - - , - - - - - - - - - -

--'

-_._--,-------

---_._-------

("

with

t~c

fifth

'

li~c:

~!inter

I~~1..r"t~~:

\:ept us

i"

,(~no~·'l,

<-:ce(~.ip(T

tu ers.

"

S1.1r:ln1 C::' Sl.l~.:-"!}:::-it:~C~(l 1.] ~, cO~:1i:,:'r: o \,7 C ?:- t.:-q:: St~2.::-· ~}~~·e~(""c~~s'2;(;

:;j_t"i. ~l 2::0\"7o.:c of r2j.r'; lve r:~-~:o~)~2,::-1. ir't t 11 0 ~olo::I?~,-~:.·~e

.~'J'Cl Hent 0"

L~ .cl..F'lic"'t,

J.'·::o t~;e l-Io: __ qc:~.:-·tc~·;,

1,:""~ dT2n': coffee;, ;-l'Cir: t2.11,:~rl fo'':- ,'1'1 >our (11. 5-1 1 ) •

l~_

Ii ttlc

covGrir1("f

~il::1rr,l,

~~Or0e"t~~1.1~t

l:i.:~e

c.'it:h

(~-~:ie('

~."

'-:;:J.".

of

SGason~l

hnrre~n8Ss.

These 1 ires ElJ:--e

location sets the scene for

found in lines 12-18.

2

prim2.J~il~/

third-voice

(:.c8cripti ~1e

~r2matic

pass2ge

Lines 5-11 are introctuced without transi-

tioD from first to second voice.

Transitional elements 2re not

to be found ir, The Haste Lanrl ;:1n0 ::or t:t"is very rea,son, Cl :r::2 r ,'.il-

ta1ze

pl:;c~.

13

ll.

\}l.... e:·,

.

, ',"

Eliot returns to

:n~.,).t

,".re

]:-oots t-'L"t c"utc",

-l:J1P

t~ri~)

-'-::r-o

.s,tOY\~.7

rl~bbi.r~:-'~

()rrt

:>:f

~[Ol.l

::2..:!~!.ot

~~

.~ .. rl:'

of 1::\~:-01?(~~: j_:·~.-:-:~fCS,

t"l,.(;

c"ocJ' -t~'""cc r'rj_\}(!~~

.!-:.rJ

t~-~.e

':.l~'

~';i

T

",~Olj.;-

I

~;.lC,?;~-:;,

O.Y

2,-~~()~~0

'J

1

~~o

,~~ho'"

11

Sl": -~:"

C'

t.

O~'.;

;::' 0": "0 '.1

IISon

~. 'Ol:

·:=O~

~·l.O

t.>.i;;~

,- i.''' ;--

,~~-:

(;,::)"e:, j_ ", - r~

~-~ -:::~

~11~c'..t

l'~''1O\'l

70 lJ.

t.:'-8

O~j

S1J.~--::

("]-OT,[

J.

"1,7

')c;:-t~"

t'-~c~

,s"""}cl-tcr,

:·~~:·j.C1"ct_

~tO

--::l.j_c:~

:-()(~~"'.,

":,-.<-, .• :\

i, . . i

(:!.j. :~: ~ ,-::; =~C~::.

Fe

"'~ -,

-"~:: ..t·:-t :."·_C~

t n

i

() r

- . ,,' .-' '.' J.

i_;

1,,-~,,C--'()~

:-::i.::.,

of

o·r- -.',-:--.1- s:c.

"·:0 -.C·;-: - j . j_: - r~

-"'~or

.C ::; -, -.-

't

\f-'~C=C9

::-;OlJ."-- -.

oS'-' ,:,,-.1 0 ,,:: 1"-;' .,:?~~

::~~.<.~~~-l_O\·}

~ "0:,' ~t_-

I -, !:'

·-.~.]:-:l

j. <:'

"'r-:-121.:-e

Ci -.-

C2.~/·

~~_cc;~

~:;or:

.'' ': !'~01:'

"l-:

~~~.:

,\701't

- "::: r::: .~-:

l' ~ I~

0;;

~01 ') ;

•

(

i.

1

O~,...

lecture state0

Eliot'~

th~t

t~e

second voice

is useel for .sC'.tirical purl?oses::n:d his juxtaposition of tlie

contempor2ry clairvoyante and her parallel in the past are what

Eliz2beth Drew labels "satiric 'levity.,"7.5

Dre,., states that

"1'1adame Sosotris, \'li th her ::.ame sU0cre:;tin0 a

Crec"~.-Err:.Tf'ti':::T

origin,

i~

2

uodcrn,

vul~0rize~

ane pr2cticers of maqic,

and to forecast the

t}j.rou~.'-1-;

t:"

LC

r~(.lrot

71.

,~o

risi~r

?e:

C~I:--C:1_G." L.~"":

vGrsio~

of

t~e

E0"Dti~n

nrofesse~

to

co~trol

f~llin~

o~

~~e

?ne

~iviners

fertilit~,

~2tcrs

of the 8i10

~O-7S

•

"You!

si"'"(":c':1:'i;-."7

:C"c'

"

o='"

i~

the

t~ird

In

~is

~nalysis

voice.

sense,

:-Jaste

Lar,J~,

.

28

DUl·ty,"

Voice.::"

I-~.

u.nc·~

G.

GeorSe

:r-efe:::'f~

of this section of The

to i i:s "qreatcr

'1a::::-Y:-~lti '1e

,'la}:'ration is, as Eliot poir)ts out i"

l[~ctu:::-c,

on2 of tile

func'ar1cl~'t::.l

co;~ti-

t.he "Three

pu!::-poc.ec of second-voice

?O

poetr}'.~.-'

27

"Eliot I s The Waste Land,

01a.y, 1965), item 7 t1 •

28

P. 17.8.

74," The Explicator,

:;'~XIII

16

Eliot

Ci.n::::. 1 i

employ~

t~e

se~ond

~s

voice

he ooens Section III,

T~ e,~

.... ~. - ~--:-- ":':"11 ..

J_OO'~

C'"

,.,_, ..:.;r" :'.'_

(1. 31 Cl

o 1~

),

,-'

1 J.

( I

"

\_,~

"'0.1o::f~-S

CUU::'.J J'l

"\

...

~

:\~c;~

.::0 :Y)':").

.... -:- -.

-1-.~

.. .,.

~

"n

"

:') ,"'

",' ,,'

' O':';~"'"

"

o

.1_-,

C.

noe-,:ic

";TC

i

-- ."-

(~2.

n·2'

:1"1

?_ . J"l/":).

['3.

_,------------'.--.'''-'-''O<------.--..--..

-,~---

"':

...

, 7

":T-,2.·;:

i'::J.io·c

r'

-_0.,'

~oC'"

;-~,7

31"Eliot ' s Tl-·e ·~IC1..c:te Land,

.'GCIV (!i:oril, 1966), i t'2E! 7~.

t:"~;c

?oei-::,

397.-395," The Explicator,

•

31

III.

h DraQatic

TEE THIRD VOICE

~har2cter

exp12ine~

Eliot

in

~is

Spe~:irg

in Verse

lecture on the

'-'otico

t~~ee

'i~

r;

r.

t

('

c

voices that

.-.,.., . . -', ..., i: C~ --

-1" '.

':. 'e

.-. _._.

__._---

'"'

"

~,:'

~J,

....J--'P.

18

---~-

.. _..

_--_._------_.

__ __._--.

19

Eliot usee t',C' t',irc1-voice tcc1.;l"deue fo,,:- t:-e fLcet tine

in. :tipes 12-18:

Bin

7\1!.(1

JOy

('far ]::eine Russin,

-'--

'·vlll.eT1 "\IC

~lC~re

:::ouE~in's,

'0

Stamn·

---,

chil(=:!J:-C~ll,

too'~

"18

.2\-:-1>t I \"l·C':.S =]:-icfl~~te~-:..c;'].•

I <' :rie, ';oh~ 01 tight.

OU-::

~=o

Li tauen, ecl'.t deutsch.

2.t -tl-,.c arC~"\Cl_1J}::e 1 s

u sloe],

aus

-

E.:t:(J.~..Ti;!r:

01

':~;1ic:,

1·~Cl.l-ic,

i r t:ro;-::11.1C c . . .

L'" '7011. ;::oe rJ.e::".r ers. ECj:ui to~".c",

TeJl ~}er I })rii~~~r -l:~--C ;-1.o::-OSCOJ?0 lTI=?S0}_:~;

0;'0 rcmst ;'8 so cC1re;'uJ. .:::.i~ . :~·~c'~()u:::~

(lJ. r; 7-r~·9) •

Section II of Tho Waste Land.

._--_..

__ _---_

...

...

3 LL

·The Poetr'.' of '1'. S. E1 iot (Lory1 on: I~outl 8('00

Paul Limited, 1958), D. 103.

c:

I~ecf2'-:'

20

:'J,e:. ~ic,

·.,c

,',;

-~ -:. T

"

i.l

,'- '" (:

• J'

::-": 'T'

..

"''"'"'.-'''-

'2

'.-

,

0:

Tl- c

result

thou~fhts

the usual

asl:s,

rn~nner

"Do you

---~-.-

\vOT.~,::lr:_ ':::;

are also significant.

of

sDeech

i~terroa~tive

remem'~er

2.nd·~er

cor.,-

The woman uses no contrac-

She doe2 not frame her many

tions in l-er speecll..

':

J_

matica.l structures \-,ri'ich corrrDose the

parlion I s

r"':',

~ .•

~uestions

in

sentences used in conversation.

,10thin0,?" anc'

;'-o~c

"Don ' t you re:-."12I'1ber

.------------------_. __ .•----- ----- - _._--------_ ..- ----_. __._--

21

She uses "shall" e2.ch time she uses tr.e firs-t

and "will."

Derson with the concept of futurity.

DrocessC!~:

j.l"11.e

•

t;1·ei]:-

2S

The sane grammaticaJ

\"~,:r

--

of

J. -F

c:

135-JJ(:)

It

I:::

-'- '~, r:-,

-',r'

.' Y',

-

.

0--;11

; 1....- ;'"! '. _ .

~

.:

r,

c. . .

,

~

, .,. ....:-:-:, -~' .~

-~

"0

," " -.

.

C:-'

.~.--

.-.1-.(>

r ,,"_

( ., "1

. "

• 1

'. r \

I

", ( '

,-

, 1

•

~,

'"..!.....

,-, n" .'- i --, ~ ..

f"'..

r

~

--,,"r'

,. . , -'-

c··'-,--:.,,-,.j-

·...:.-'0··'1.

L . . ,--,

~~~ . . c~ C ;-: C ~~.r1o:1

---,

..---_.. _.

-

0 -.-

;lc -'.

__._---------" ---._-----------

r~;:-:- ~~ c~ ;ll~::-'t.r

-"- .

---.--"-~----

'0

0

f

: ;"oc~" 2r~"'l"

PO(-~ -1::::'

·:~i '0.

.'- r""

re;:c=7

',(,:

-:-:1-: e

(:"ro~,~

01.

1/0, 1':;7)

1 /

L

lOc:.- 1

-';

"'.rc

;-'

.,

.,

(, 1

o.

)

'; 0 ' " 0

10

~f11

c:;

i.

i

.

"1')1.l11in r ; ,-.

101'(0

to enforce

t~e

.

,"

J=:-.F""C "I

,'- \. . \.,,- ..... ~

colloqui~l

to~e

of the nonolonu6.

T1-. e .sneaker

('100S

In

mono] oQlle

i,C)

m3c~e

111:-')

en.ti::(~l"C.r

subject [lc:tter but alno in

o:c

l~er

contr~st

~o

the firrt

c'rL.S'\,'leI"S.

'7ocC'}-:'ul;).ry.

con.te~:t.

anrl sentence structure,

e:-:ists.

social

Qn~

it is

~pprODriat~

,

that the vari2tion

Eliot was 2ttenpting to represent opposite ends of the

sc~le,

and he chose to do so by employing the language

spoken by the two extremes in the poetic

thir~

voice.

The

rigid, sterile, hysterical, and futile speech of the bored

upper-class woman is shaned by a hrand of existence for which

the same adjectives are applicable.

The second speech, 1·Jhich

lacks sensitivity, oriqinality, and organization, establishes

a prevailing mood of resicrnation and despair which is heightened

by the poet's ironic one-line closina comment deliverea in the

first voice cmd echoinq Sha}:espeare';;: OpheliZl, a trou':>len.

lE~d'.'

of a different sort:

ladies, good ntght, good right"

Still another

foun~

in Section III,

(1.

thir~-voice

172).

characteriz2tion is to he

to T;Jri-::e, but also

]11<'\]:c

use of Tiresic::s' par cicl'!.2.': viei'JJ

Doint.

nossesses

(1.

o~~i~ciept

unde~starding

whic~

t~e

poet

~learc

fro~

~29).

I':~

is

(-.:."1.0

1~,S

t.O

:~i.O:

Q;:-r

~.;,

__ i r

;)]:-e.ser:<~0

541-.cic-l::::·_~t

10"7(;

co-·-'c.lrl<~~'":!

;:-:rcl

O~(:

:-li,~~

t.~-i;-,"t

25

r]:j~r,:.:.'~i2::

:31J.l-·::~eql~le~"'+:

I1rr~"c

I~:.~-!::r;

t:o i:i::is

l:!i-tt~e,s"-;

:J

C·O:-'1f.'":CT,:t.S

I_,,?J'.(-rl

c1_c~"'1,r

o~

it

''-IO~;:::

L10 ::O~:-~-.

.:-~.~ :-.!--

n---1}"'''

':-;:'~i;::;-;}

~,~i-t11_

e

-t:~,?

~-:

() _r

('c. '-, ',- ::-: c )

-: ", ( '

'- '

,. -:

-

,

:::OC-3 0'_ ) •

c: ~

but all L:.re Eliot 's ;;:ttemp-t to prc,se:lt ;:,

for }'1iilself.

Of course, tll.e l')oet

IS

cl-;2~:-acter

~1ho

~'liIJ

'"\7oice is also 11.eLlrd, :cor

38The Complete Poems and Plavs, p. 53.

spe0,}-:

l~!e

of

300'-.~

o~

t:O

CO~!."\7e~,:".

Eliot's

crnft~B~p~~ip.

,

.

'-::'J S

lectu:ce.

As

in

1-. i ,<,

o~

the three voices

~elmor8

~~oul~

Schw2rtz proposed, the

cl~ssific~tion

be 2nplicahle, first of ?ll, to Eliot's

own Doetry.

It rlay be,

a::: Ivlc:..:"Cvin Hudriclr, hus St2tcc1

,

that t''1e "dif:i"use-

ness soliei tee':: by a public occasio!1" hC'l.:'; left Eliot' ,".:; critics

the opinion that the thcory,

\,;i tl-,

as advanced by the poet, fuiled to

provide enoug}"\ inform:ltion \vi th

whic~

Gr~~~:l.t:-

to test i-t:,c; v21idi ty.

i)':g Hudrick' s poi:1t, however, coe;:, not pe0?:l.te tr'o cs,<:;c::-tiO,13 whic'-'

Eliot

:_1~~S

n2G.e.

Elioe

.-~ .. ro

~-~ ,,")

'-

i1:'-:C

'-

i -.

(',.'i +:}, 011 'i:

"

r-

,'?

C'

c: >'~~.. -~~

':

27

contained within his poetry.

If his theory falls short of

completeness or lacks mathematical precision, it is little

different from other explanations of the creative process

which have thus far been advanced.

Is it not enough that

within his poetry itself there exist concrete examples of the

theory?

After the language of the poem has been examined, after

the allusions have been identified, after the poet's message has

been assimilated, there still remains the essence of the poem

which is closer to its creator than anything else.

It is the

manner in which the poet employed the language and the allusions

to obtain a total effect.

The complex mental process may never

be totally understood, but it is surprising that when one of the

greatest poets of our century endeavors to put into words his

thoughts on the subject they are received with so little comment

by his critics.

One could gloss over the importance of Eliot's explanation,

as Schwartz asserts, with the assumption that the poet was merely

restating what has been known for some time about literary techniques.

With an analysis which provides as many examples as does

The Waste Land, however, it is difficult to dismiss Eliot's comments

as mere restatement of known facts.

The poem contains numerous ex-

amples of each voice and each voice possesses unique characteristics.

The voices can be distinguished and catalogued.

Knowledge of the

theory and the ability to recognize the poet's use of each voice

enhance the reader's appreciation of the total poem.

The lack of

transitional elements becomes less of a difficulty when one understands that a change in poetic voice has occurred.

Some insight

28

is to be gained into the complexity of the process and development

of the art form, not to mention the quality and depth of understanding which accompany an analysis based, in part, on an awareness of Eliot's theory.

It would be deemed short-sighted, if

not stupid, to ignore the poet's punctuation, imagery, or allusions

when readin9 his poems.

Would it not be equally presumptuous to

dismiss lightly his earnest attempt to explain one of the methods

by which he puts his thoughts into written form?

BIBLIOGRl:;PHY

ldken, Conrad.

:srooks,

IIj\n.

?\'n2.to:'~y

of

l~elancholy, 11

The SCHanec Rcvim.',

1956, Srcci21 ISslte), 188-96.

(Jnnuary-M~rch,

L~;:~IV

"T.S. :81 :\0-;:' :::":L1~(e::::- i:nc'! .'~rtist, 11 'T'le

Revic\J, L :~~I V (2',~ 'iU =,'.-'7- La:::-c',. , J ') 6:-:; , S-')cci." }.

,u,.sue), 310-76.

Cle.?,2:1t~l.

SE~'...J2nee

'~~:h.e

~:clC<l_::-'~()n

Trea.r_:~~2;)_~

~-o:-~(,

0t

~ ~·Io(tcr·-'.

I>oc-~-:,s

!:o2c1i. ~\:-, TC 200 G,

.:.~C~!

!:.~,.

Drc','7,

" C'l'

TleJ

t. ,

Eliot.

C'l~

nt,-l

--

c.

~~_-:.C'

::;e~··:t:.~·~C>~

S~eci~l

:~C2~;)C.~~t.

;.,)

.

,'c;o--.C

:~C:-<"Ti c~."

~~suC:),

I.J~C~'=IT/

239-~~.

I!E}__10 i -,, S

Ec~::-JJ.ic2tor,

IC::--::-.I":-'er,

.

=0!:111

0·-:_~lc.

'1Eliot·.-:. T~~~(;

:'==CIV U, ny j l, 1 9 6 7

r;

1~ L~_-t t.~-li G,,(~ ,:: c:!:'-l,

~~or'::

2.-~ <'-. i;:::

O:;:forc

:2' r

7.9

.

(J ~-:." ': 1, ,~~' .~\ 7-J =~_~ ~c;--.

,

,

II

30

I"Itlcl:~ic~'~~,

l~.~~r~li~'1.

Revi e\v, :;=

Sch~J~.rt::::,

Delmore.

"TLe T'>JO Voices of Pr. Eliot,"

(~jnter

1957-58), 599-605.

"T. S. Eliot ';:; Voice

L.iC:::V (JCi.TIuary, 195')},

2.'lC~

IUs Voices," poetry,

232-,~2.

Williamson, Hugh Ross.

The Poetry of T.S. Eliot.

Hodder & Stroughton Limited, 1932.

Lonc"or: :