Three Australian Asset-price Bubbles

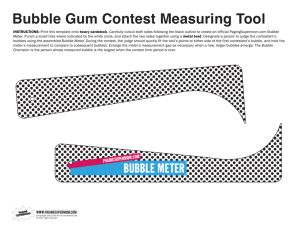

advertisement