Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East and Japan’s Trade Structure

advertisement

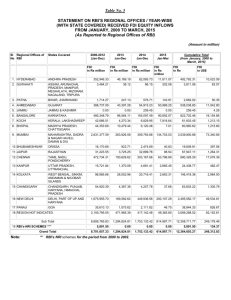

156 Kazuhiko Ishida Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia: Its Influence on Recipient Countries and Japan’s Trade Structure Kazuhiko Ishida* 1. Increase in Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia Following the sharp appreciation of the yen after the Plaza Agreement of September 1985, Japan’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in East Asian countries increased rapidly: from around $US1 billion during the first half of the 1980s, it started to increase sharply in 1986 and hit a peak of around $US8 billion in 1989. This rapid increase then stopped as the appreciation of the yen slowed during 1990-92, although the level has stayed around $US6-7 billion (Figure 1). However, it should also be noted that Japan’s total FDI has increased significantly since 1986, and that East Asia has not necessarily been the major investment destination for Japan (Figure 2). The main factors that have driven this rapid increase in Japan’s FDI in East Asia can be summarised as follows: • the appreciation of the yen; • the aggravation of trade friction; • lower wages in East Asian countries; and • imports from East Asian countries. The appreciation of the yen after the Plaza Agreement was regarded as irreversible by most Japanese firms and, since corporate ability to maintain export volumes by squeezing profits was thought to be very limited, firms tended to respond by effecting structural changes to improve their competitiveness in international markets, including shifting production overseas. In spite of the sharp appreciation of the yen, Japan’s trade surplus did not decrease significantly until 1988, which further aggravated trade friction. Voluntary export restrictions vis-à-vis the United States and EC countries were introduced or strengthened in certain areas (automobiles, machinery etc.). In some cases, anti-dumping duties were imposed on Japanese exports. These restrictions on exports also prompted Japanese firms to shift production out of Japan. While some (mainly automakers) shifted production directly to North America and Europe, others chose to set up production sites in East Asian countries from which to export to the United States and Europe. For most Japanese firms that have chosen to invest in East Asia, the main reason to shift their production was, at least initially, to take advantage of lower wages in these countries so as to improve their competitiveness in international markets. For example, * The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Japan. Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 157 Figure 1: Yen/US Dollar Exchange Rate and Japanese FDI in Asia Yen appreciation Yen depreciation ¥/$US $USb 8 200 150 6 Yen/$US exchange rates (LHS) 100 4 50 2 Japanese FDI in Asia (RHS) 0 1980 Note: Source: 0 1983 1986 1989 1992 J F M A M J J A S O N D 1993 The yen/$US rate is a central rate average. Ministry of Finance, Annual Report of International Finance Bureau; Bank of Japan, Economic Statistics Monthly. Figure 2: Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment (manufactures, by area; fiscal years) $US100m 160 160 North America 140 140 Asia Europe 120 120 Others 100 100 80 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 1970 1975 0 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 158 Kazuhiko Ishida in 1986, average real wage costs in newly industrialising economies (NIEs) were only slightly more than 20 per cent (and in ASEAN countries less than 10 per cent) of the figure for Japan. While most of the components were, at least initially, exported from Japan, the assembly process, which is relatively labour intensive, was shifted to low-wage countries in East Asia. This kind of production shift to East Asian countries can be thought of as a typical example of the most important structural response to the appreciation of the yen – that is, restructuring domestic production to specialise in high-value-added products. Similar to high-value-added final goods, certain components which require a high level of technology and a well-trained workforce remained competitive in spite of the sharp appreciation of the yen, as there were few competing producers. These components, therefore, could be, and in fact had to be, produced domestically. On the other hand, the assembly process, which does not necessarily need such high technology, nor such skilled workers, could be shifted to countries where wages were lower so as to improve the price competitiveness of the final product. Whilst initially the main purpose for Japanese firms to invest in East Asian countries was to improve their competitiveness in international markets, as this shift proceeded, Japanese firms started to import certain products from their production sites in East Asia (Figure 3). This was especially the case for low-value-added or ‘lower-end’ goods. For these goods, competition in the domestic market is also high, and firms have tried to become more competitive by importing from their affiliates in East Asian countries where production costs are lower. In fact, in recent years, importing from overseas Figure 3: Imports from Overseas Affiliates (manufacturing) $USb $USb 90 90 Europe 80 80 North America Asia 70 70 60 60 50 50 40 40 30 30 20 20 10 10 0 0 1980 Source: 1983 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 MITI, Basic Survey on Japanese Business Activities Abroad. 1991 Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 159 affiliates has been cited by a number of firms as one of the main reasons for undertaking FDI, especially in East Asia. For example, according to the survey published by the Export-Import Bank of Japan, more than 20 per cent of firms which invested in ASEAN countries in 1993 raised this reason; the corresponding figure being around 20 per cent in the case of China, and 12 per cent for NIEs. 2. The Influence of Foreign Direct Investment in East Asian Countries As suggested by Figure 4, from the viewpoint of recipient East Asian countries, movements in the inflow of foreign direct investment can be classified into the following three stages: • Investment in NIEs first increased during 1986-89. This was mainly because these economies provided a reasonably good environment for foreign investment in terms of infrastructure, level of education, institutional framework and political stability. • Second, investment in ASEAN countries increased during 1988-90. This was because, by then, the wage level in NIEs had increased significantly, reflecting their own rapid growth (that is, the benefit of lower wage costs had largely been lost in NIEs). Even NIE firms started to invest in ASEAN countries as they gradually lost their competitiveness due to higher domestic labour costs as well as exchange rate changes vis-à-vis the US dollar. • Since 1990, investment in China has grown dramatically in line with the opening up of its economy. The share of Japan’s investment in total FDI received by these economies has been around 30 per cent in NIEs and around 20 per cent in ASEAN countries. In the case of China, Hong Kong occupies by far the largest share, but this is because foreign investments, including those from Japan and the United States, made through affiliates in Hong Kong are included. This rapid increase in FDI has had a significant impact on East Asian countries, not only economically but also socially. The scope of this paper, however, is limited to economic effects, which can be classified into three areas, namely: supply capacity, foreign trade and domestic demand. 2.1 Influence of FDI on Supply Capacity The increase in FDI has influenced the supply capacity of recipient countries by effecting shifts in industrial structure, increasing labour productivity and contributing to production technology. During the 1980s, in most East Asian countries, the primary sector decreased as a share of GDP while the secondary and tertiary sectors grew (Figure 5). This kind of change in industrial structure is, of course, seen in many industrialising countries, and it is not clear to what extent it can be attributed to the increase in FDI. Figure 6 indicates the relationship between shifts in industrial structure and the increase in FDI for Malaysia and Indonesia, where relevant annual data are available. It can be seen from this figure 160 Kazuhiko Ishida Figure 4: FDI in NIEs, ASEAN and China (a)(b) $USb 8 NIEs(c) 6 Others (41.6%) 4 US (29.8%) 2 Japan (28.6%) $USb 20 (c) ASEAN 15 Others (41.9%) 10 US (10.4%) 5 NIEs (27.7%) Japan (20.0%) $USb 50 40 China(d) Others (19.4%) US (5.4%) Japan (3.7%) 30 20 Hong Kong (71.5%) 10 0 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 Notes: Source: (a) Amounts are those approved by the governments. (b) Based on the most recent available data. (c) For Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia manufacturing sector only. Indonesia excludes financial and oil and gas sectors. (d) Investment in China from Hong Kong includes indirect investment by United States, Japanese and NIE firms via Hong Kong. JETRO, Cross-Border Direct Investment of Japan and World: Investment. that the shift in industrial structure has taken place broadly in accordance with the increase in FDI, which suggests that FDI has played a significant role in changing industrial structure in these countries. It seems likely that this has also been the case in most other counties, although data availability is too limited to present clear evidence. In the case of NIEs, the increase in the share of the secondary sector had halted by the mid 1980s and, in fact, the share has slightly fallen since 1985. This might be because the tertiary sector has been growing more rapidly in line with the growth of consumption in these economies, as argued later. Labour productivity, measured in terms of real GDP per worker, has been on a steady increase in most East Asian countries since the 1980s (Figure 7). Although, again, it is Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 161 Figure 5: Sectoral Composition of GDP (per cent) % 100 80 NIEs 49.1 52.0 54.8 55.2 Teritary sector (a) 42.2 41.0 39.9 40.1 Secondary sector(b) 8.6 7.0 5.3 4.7 60 40 20 % 100 80 Primary sector(c) ASEAN 38.9 44.1 43.8 Teritary sector (a) 36.7 34.1 37.6 Secondary sector(b) 24.4 21.8 18.6 Primary sector(c) 60 40 20 % 100 80 China(d) 20.6 25.1 28.0 27.3 Teritary sector(a) 49.0 45.2 43.6 46.1 Secondary sector(b) 30.4 29.7 28.4 26.6 Primary sector(c) 1980 1985 1990 1991 60 40 20 0 Notes: Sources: (a) Services, etc. (b) Manufacturing, mining and construction. (c) Agriculture, forestry and fisheries. (d) GNP basis. Asian Development Bank (ADB), Key Indicators of Developing Asian and Pacific Countries; and local statistics. not clear to what extent FDI has contributed to this improvement, in most ASEAN countries (except the Philippines) it seems to have played a major role. This is suggested by the fact that the acceleration of labour productivity has coincided with the rapid increase in FDI, and that the share of FDI in aggregate domestic investment remains at an extremely high level. Comparing the development of the capital equipment ratio with FDI in Thailand and the Republic of Korea (for which statistics are available), there is a clear sign of labour productivity improvement in Thailand in the second half of the 1980s, with FDI serving as a locomotive enhancing the ratio. In the Republic of Korea also, developments in the capital equipment ratio generally coincide with those of FDI received (Figure 8). 162 Kazuhiko Ishida Figure 6: FDI in Relation to Industrial Structure $USb 6 % 41 Malaysia 40 5 4 39 Share of secondary sector in GDP (RHS) 3 2 38 37 FDI in manufacturing (LHS) 1 $USb 6 36 % 21 Indonesia 5 20 4 19 3 18 Share of secondary sector in GDP (RHS) 2 17 FDI in manufacturing (LHS) 1 16 0 15 1985 Sources: 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 JETRO, Cross-Border Direct Investment of Japan and World: Investment; ADB, Key Indicators of Developing Asian and Pacific Countries. The increase in FDI is expected to contribute to the progress of production technology in recipient countries (technology transfer). This effect is very difficult to quantify. It could, for example, be guessed from the increase in the share of industrial products in total exports and the increase in exports to industrial countries (Figures 9 and 10), which will be mentioned later. It is, however, often argued that those exports are still produced by the affiliates of firms from Japan and other industrial countries. Thus the extent to which the technology has been well transplanted in recipient countries might be questionable. 2.2 Influence of FDI on Foreign Trade In accordance with the shifts in the industrial structure induced by the increase in FDI in East Asian countries, the structure of their exports has changed gradually. The share of industrial products in total exports has grown significantly since the mid 1980s and the share of primary products has decreased (Figure 9). This change is supposed to have contributed to making their export earnings less sensitive to movements in commodity prices, which has laid a solid basis for their stable growth. The contribution of net exports to their growth, however, has remained fairly limited, because their imports have also increased broadly in line with exports (Figure 10). This increase in imports can be mostly attributed to the import of capital goods and intermediate goods (various components) associated with FDI. It should, however, be Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 163 Figure 7: Real GDP per Worker (1980 = 100) Index Index NIEs 180 Taiwan 160 180 160 Republic of Korea 140 140 Singapore 120 120 Hong Kong Index Index ASEAN 150 150 Thailand Malaysia 130 130 Indonesia 110 90 110 90 Philippines 70 1981 Sources: 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 70 Bank of Japan, Foreign Economic Statistics Annual; ADB, Key Indicators of Developing Asian and Pacific Countries. noted that, without the expansion of their export market induced by the shift in their export structure, the increase in their imports of capital goods would not have been possible, which would have significantly limited their economic growth. In addition, because of the change in the export and import structure in each country induced by the increase in FDI, regional trade flows have changed significantly (Figure 11). For example, the value of trade (exports plus imports) between the United States and NIEs doubled between 1985 and 1992, and that between Japan and NIEs tripled, at least partly reflecting ‘indirect’ exports from Japan to the United States through NIEs. A similar pattern is also observed for ASEAN countries. Furthermore, the expansion of inter-regional trade flows among NIEs, ASEAN countries and China, is also significant. This expansion of inter-regional trade seems to reflect strengthening of mutual economic ties, especially the establishment of the horizontal division of production among those countries, which has gradually grown as a result of the increase in FDI. 2.3 Influence on Domestic Demand The increase in FDI, combined with domestic investments induced by FDI, seems to have resulted in an expansion of job opportunities in East Asian countries, which has contributed to a rise in personal income, and hence personal consumption. The increase in domestic demand induced by FDI through this channel is likely to have also supported 164 Kazuhiko Ishida Figure 8: Capital Equipment Ratio in Thailand and Korea(a) $USb Thailand 2 $USb $USb 0.9 2 Value of FDI received 1 1 Index(b) 300 10 0.6 0.3 0.3 Capital equipment ratio (RHS) 300 5 200 Capital equipment index (LHS) 100 0 -10 0 1981 1984 1987 1990 Notes: Sources: 10 5 200 -5 0.9 Value of FDI received 0.6 (b) %(c) Index Capital equipment ratio (RHS) Republic of Korea 100 0 Capital equipment index (LHS) 0 -5 -10 1982 1985 1988 1991 (a) Capital equipment to labour ratio (K/L) and accumulated investment (K) from 1965, on the assumption that annual capital depreciation is 6 per cent. (b) Index, 1980=100. (c) Annual percentage change. IMF, International Financial Statistics; and local statistics. the high growth enjoyed by East Asian countries in recent years. In fact, parallel increases in FDI, labour income and personal consumption can be observed in NIEs, ASEAN countries, and China (Figure 12). 3. Influence of the Increase in Foreign Direct Investment on Japan’s Trade Structure The rapid increase in Japan’s FDI has also affected Japan’s own trade structure. Noteworthy is that while the share of Japan’s FDI in East Asia is not so large compared with Japan’s total FDI, its influence has played a significant role in changing Japan’s trade structure. First, the rise in FDI has resulted in an increase in so-called ‘induced’ exports. At the initial stage of overseas production, capital goods (mainly production equipment) are usually exported from Japan. Then, once production has started, many components for production are exported. In fact, a significant increase in exports to overseas subsidiaries has been observed in line with the increase in FDI (Figure 13). This increase in induced exports has been particularly significant in the case of FDI in East Asian countries because the supply of capital and intermediate goods has been very limited in these countries. An increase in induced exports is expected to lower the price elasticity of Japan’s exports, because induced exports tend to respond less to exchange rate fluctuations. Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 165 Figure 9: Share of Export Items % 100 NIEs 7.7 9.4 8.5 6.6 73.0 76.7 81.7 83.7 12.5 6.8 9.1 4.8 6.0 3.8 5.9 3.8 80 60 40 20 % 100 ASEAN 2.8 3.6 16.7 80 3.7 25.7 50.9 60 40 63.2 51.0 28.8 20 17.3 % 100 19.7 16.6 China 1.1 12.4 18.7 19.0 55.7 58.5 80 48.6 37.1 33.0 35.6 17.3 14.9 60 40 20 0 1980 Primary Sources: 1985 Mining 14.2 11.5 11.5 11.0 1990 Industrial 1991 Others ADB, Key Indicators of Developing Asian and Pacific Countries; Bank of Japan, Foreign Economic Statistics Annual; and IMF, International Financial Statistics. Second, as stated before, restructuring of domestic production has taken place in accordance with the increase in FDI, so that domestic production has come to be more specialised in high-value-added goods. These high-value-added goods are often technology intensive, and hence exhibit strong non-price competitiveness. Export of these goods, therefore, tends to be less sensitive to changes in the exchange rate, resulting in the lower price elasticity of Japan’s exports. As a result of the two above-mentioned factors, Japan’s export volume is expected to have become less elastic to changes in the exchange rate. In fact, the elasticity of Japan’s export volume to the relative price factor is found to have decreased significantly for the estimation period after the Plaza Agreement (see Table 1 results for 1986-92).1 1. It should be noted that structural changes took place continuously during the estimation period, and hence the estimated parameters could be different from those to be obtained after all the changes have been completed. This is also the case for Table 2, where the results seem more puzzling. 166 Kazuhiko Ishida Figure 10: Share of Imports and Exports in GDP (per cent) % 65 % 65 NIEs(a) 60 60 Exports (b) 55 55 50 50 45 Imports (b) 45 40 40 % % ASEAN 40 40 35 35 Exports Imports 30 30 25 25 20 20 1975 Notes: Sources: 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 (a) Excludes Singapore. (b) Calculated using the figures of exports and imports from the national accounts. IMF, International Financial Statistics; and local statistics. Table 1: Parameters of Export Volume Equations Estimation period 1975:1 – 1985:4 1986:1 – 1992:3 Income factor 1.75 0.50 Relative price factor -1.53 -0.62 Third, on the import side, the shift of production of low-value-added or ‘lower-end’ products overseas, associated with the increase in FDI, has resulted in an increase in imports from Japanese firms’ overseas affiliates. This, again, has been particularly the case for FDI in East Asian countries because the shift of production of this category of goods has been mainly directed to these countries where the advantage of lower wages is larger. For individual firms, this shift has meant the establishment of the horizontal division of production between domestic factories and those overseas. Once this division has been established as a result of FDI and importing from overseas affiliates has commenced, the existence of ‘sunk costs’ tends to prevent frequent adjustment in such imports. For example, import volumes are less likely to decrease immediately even when the yen Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 167 Figure 11: Changing Trade Patterns (a) 1985 Japan(b) 95 22 (39) (9) 24 9 (10) (0) US(c) (f) China 31 16 14 (7) (2) (11) 2 (0) 56 (21) 15 NIEs (3) (d) ASEAN(e) 1992 Japan(b) 152 (47) US(c) 30 (2) 37 55 (18) (1) China(f) 92 40 57 (39) (9) (12) 6 (0) 112 (9) 52 NIEs(d) Notes: (1) ASEAN(e) (a) $US billion. Trade values of exports and imports. Figures in parentheses represent trade balances. Intermediary trade via Hong Kong partially adjusted. (b) Trade values between Japan and other partners excluding China based on Japan statistics. (c) Trade values between US and China/ASEAN based on US statistics. (d) Trade values between NIEs and China/US based on NIEs statistics. (e) Trade values between ASEAN and NIEs/China based on ASEAN statistics. (f) Trade values between Japan and China based on China statistics. 168 Kazuhiko Ishida Figure 12: Personal Income, Consumption and FDI ($US billion; annual percentage change) $USb % NIEs 9 (83.5) (84.5) (85.3) (86.2) 12 (82.1) 8 6 3 4 (80.6) 0 ASEAN 0 (45.3) 10 25 8 20 (47.4) (44.3) 15 6 (44.3) 4 10 5 2 (45.1) (44.2) 0 0 China (40.0) 12 9 24 18 (38.7) (39.6) 6 12 (40.3) (39.7) 3 (38.7) 6 0 0 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 (a) Value of FDI received (LHS) Real personal consumption (RHS) (b) Real labour income (RHS) Notes: Sources: (a) Values of FDI are those approved by the governments. For Singapore and Malaysia, manufacturing sector only; for Indonesia, excluding finance and oil and gas. Figures in parentheses represent share of workers engaged in secondary and tertiary sectors on a GDP basis. (b) Figures represent labour income of workers in secondary and tertiary sectors on a GDP basis. IMF, International Financial Statistics; JETRO, Cross-Border Direct Investment of Japan and World: Investment; ADB, Key Indicators of Developing Asian and Pacific Countries, and local statistics. Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia 169 depreciates. In other words, at least some of the influence of exchange rate changes can be absorbed by each individual firm in terms of the reallocation of profit between head office and overseas subsidiaries. This could be a possible factor reducing the elasticity of Japan’s imports to exchange rate changes. In fact, the price elasticity of Japan’s import volume seems to have fallen slightly (from -0.33 to -0.26) since the Plaza Agreement (Table 2), although it is questionable whether or not this fall is statistically significant. Taking account of the fact that this observed fall during 1986-92 took place against the background of various structural measures to promote imports, it seems that the influence of the increase in FDI on Japan’s imports has, in fact, been significant. Table 2: Parameters of Import Volume Equations Estimation period 1975:1 – 1985:4 1986:1 – 1992:3 Income factor 0.88 1.04 Relative price factor -0.33 -0.26 In conclusion, it is likely that these changes in Japan’s trade structure induced by the increase in FDI have made Japan’s trade balance less sensitive to exchange rate changes. It is, therefore, possible that changes in the exchange rate have become less effective in adjusting the trade imbalance as a result of the increase in FDI. Figure 13: Exports to Japanese Overseas Subsidiaries $US100m Per cent of total exports (RHS) 500 375 16 12 Export value to subsidiaries (LHS) 250 8 125 4 0 0 1980 Note: 1983 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 Export value equals total purchases of Japanese overseas subsidiaries multiplied by the per cent of purchases from Japan, in each fiscal year.