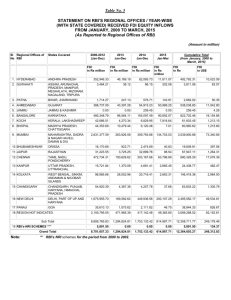

Internationalisation, Trade and Foreign Direct Investment 1. Introduction

advertisement