Bulletin DECEMBER QUARTER 2015 Contents Article

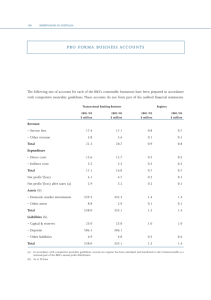

advertisement