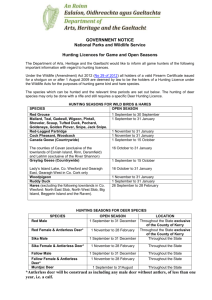

Redacted for privacy in Fisheries and Wildlife presented on

advertisement