Document 10795678

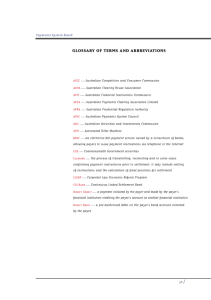

advertisement