.ll.i.wi

advertisement

A Comparison of the Roles of the Hero and the Seductress

in the Tajn Bo Cuajlgne and the .ll.i.wi

An Honors Thesis (HONORS 499)

by

Mark Hayes

Thesis Advisor

Professor Frederick Suppe

~-,

,fo~0><-;;' . ~/;T<-e..

Ball State University

Muncie,

Indiana

April 19, 1994

Graduation

Date

May 7, 1994

/

~

.

Purpose of Thesis

This paper attempts to redefine the role of the "hero" in ancient

Western epic poetry, focusing specifically on the II i ad of Homer and

the Irish epic the Tajn Bo Cuajlgne, by focusing on the maintenance of

a hierarchy of

loyalties.

Similarly, this paper demonstrates the need

to expand the traditional conception of the epic seductress.

Ultimately, the paper concludes with a brief cross-cultural comparison

of ancient Greece and Ireland based on information extracted by

employing the revised definitions suggested in this paper.

-

Acknowledgements

I would to thank Dr. Frederick Suppe (Department of History) for

introducing me to the Tain Bo Cuailgne in his Irish History course

during the Spring Semester of 1992, and for his guidance throughout

the course the the project.

I would also like to thank Dr. Abel Alves

(Department of History), Dr. Edward Kadletz (Department of Modern

Languages and Classics), and Jennifer Lynn Wallace (undergraduate)

for reviewing the paper while it was in progress and for their

comments.

In addition, I would like to thank Dr. Ronald Hicks

(Department of Anthropology) for mailing me a copy of the I..al.o. by

Thomas Kinsella while he was teaching abroad in Great Britain.

Finally, I would like to extend my sincerest appreciation to Sara

Gallagher for working with me to develop my pronunciation of the

Irish proper names which aided me in my presentation of a smaller

version

of this paper at the Twenty-Fourth Annual

Interdisciplinary

Committee for the Advancement of Early Studies (CAES) Conference at

Ball State University on October 15, 1993.

-

A Comparison of the Roles of the Hero and the Seductress

In the Tajn Bo Cuailgne and the Iliad

The term "Heroic Age" encapsulates the theory of H.M. Chadwick

which he developed in his book Heroic Age and later in various

chapters of The Growth of Literature.

This theory holds that the

evolution of every society is marked by an early period of domination

by an aristocratic warrior class.

The Heroic Age of a society is

generally credited with the production of long narrative epics that

were designed to be delivered in verse form, usually to the

accompaniment of a stringed instrument, such as the lyre 1 or the

harp2,.

The study of ancient oral epics and the examination of

individual heroes or bands of adventuring warriors has fallen under

heavy criticism, with much of the harshest criticism being deserved.

All ancient epics only reveal a limited amount of factual information

about the culture and time period that produced them.

The true

challenge is to evaluate the information about the epic's parent

society to ascertain how much of the extracted material can be

validated.

Therefore, ancient epic is often a poor substitute for

archeological evidence or literature created outside of an oral

-

.

H.D. Amos and A.G.P. Lang. These Were the Greeks. p. 27.

2 Alwyn Rees and Brinley Rees. Celtic Heritage: Ancient Traditjon in Ireland and Wales.

1

p. 141.

,-

2

tradition

when

attempting to

produce cultural

or

historical

specifics.

However, ancient oral epics should not be ignored when studying an

ancient civilization, because heroic literature provides a broad view

of the general structure and nature of the parent society.

This

information alone makes the study of ancient oral epic vastly

rewarding.

However, beyond providing an over-arching view of the

parent culture's societal institutions in operation, oral epics also lend

a key insight into understanding the abstract notions of the parent

society.

Among the most basic and important of these abstract

notions, or cultural icons, in ancient oral epic are the roles of the hero

and the seductress.

The characters of the hero and the seductress are standard

elements of nearly all epic sagas, and often they are presented within

the context of their individual epics in a strikingly similar manner.

This facilitates the cross-cultural comparison of epics and epic

characters.

Naturally, these cross-cultural comparisons of epics

generally rely most heavily on the

.ll.i.a.d.. of Homer, since it is one of the

the oldest works of oral epic in the Western Tradition, and it is

considered to be the corner stone of Western literature.

In contrast

to the Iliad, the ancient Irish epic the Tain Bo Cuailgne remains

relatively unknown and has often been overlooked.

-

The Tain Bo Cuajlgne has frequently been referred to as simply

-

3

the Tajn. since it is the most common of several Irish tales with titles

beginning with the word "Tain," a Celtic Irish word meaning a "cattle

raid"3.

The lain is part of the Ulster Cycle of tales, which deal

primarHy with the heroes of the Ulaid, a people who lived in Ulster,

the northeastern section of Ireland, and maintained a capital at Emain

Macha 4 •

These warriors have also been referred to collectively as the

Heroes of the Red Branch 5 •

Although various dates are given for the

Tain's authorship, certain parts of the standard text clearly date back

to the eighth century A.D., while some verse passages may be older by

at least two centuries.

However, most Celtic scholars believe that the

Ia.i.n... along with the rest of the Ulster Cycle, has origins that predate

the introduction of Christianity into Ireland in the fifth century A. D.

The traditional time frame given for the events described by the

Ulster Cycle was roughly the birth of Christ and the reign of Caesar

Augustus, but recent scholarship has shown that the culture being

described in the Ulster Cycle could have existed up to the introduction

of

Christianity

into

Ireland 6 •

The text of the Tain is preserved primarily in three medieval

Irish

manuscripts,

The Book of the pun Cow, The yellow Book of Lecan,

and The Book of Lejnster.

3

4

5

8

Unlike the faultless poetry of the Homeric

Patrick Denneen (compiler and editor). An Irish-English Dictionary. p. 1158.

Miles Dillon. Early Irish Literature. p. 1.

Eleanor Hull. The Cuchullin Saga in Irish Literature. p. Iv.

Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tain. p. 256.

4

epics, the lain came into written

literature as narrative prose with

segments of poetry to accentuate the dramatic speeches of the main

characters.

These poetic passages are often alliterative in nature

with a word order that is archaic or completely artificial.

the style of the Tain and that of the

.l.l.i.wi reflect

However, if

dissimilarities,

structure and the subject matter bear a striking resemblance

the

7

•

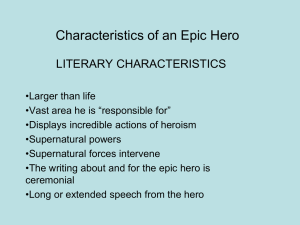

In his book, the Heroic Age, Chadwick lists some general

characteristics of Heroic Age literature which certainly apply to both

the Iliad and the Tain.

Both epics concentrate on the aristocratic

caste and their values, which center primarily on courage, prowess in

battle, loyalty, and sincere dedication to personal honor.

profession of choice among the aristocracy in both epics.

War is the

The type of

war fought almost always follows the deeds of individual heroes in

direct combat and is usually devoid of any coherent strategy.

Heroes

are presented in an idealized human form, but they still must suffer

pain, both emotional and physical, and even death.

Ultimately, Heroic

Age literature presents the lives of the aristocratic warrior class in a

setting that readily provides them with the opportunity to be heroics.

The warriors of the

.l.lia1i were afforded the chance to gain honor

and glory when the Achaians of mainland Greece, Thessaly, and some

of the surrounding islands waged war on the city of Troy in Asia Minor

7

JJlli1. p. 257.

8

H.M. Chadwick. Heroic Age.

-

5

and all of that city-state's allies.

The war began when Paris, a young

Trojan prince, while a guest in Sparta of Menelaos, carried off

Menelaos' wife Helen.

Once Paris returned to Troy, with Helen living

with him as his wife, Agamemnon, the older brother of Menelaos,

gathered together the princes of the Achaians and sailed to Troy,

determined to retake Helen, and to avenge the insult to Menelaos'

honor by sacking the citadel of Troy.

Once on Trojan soil, the Achaian

forces managed to keep the Trojans and their allies on the defensive

for nine years.

In that time, the Achaians also plundered many of the

smaller cities and towns surrounding the walled city of Troy.

narrative of the

The

l.lla.d. begins in the tenth year of the siege of Troy, and

focuses on a quarrel between Achilles, the best warrior of the

Achaians, and Agamemnon, who acted as the commander-in-chief of

the Achaian forces at Troy.

As a result of this quarrel, Achilles

withdraws himself and his men from the fighting.

Achilles then has

his mother, the goddess Thetis, persuade Zeus to allow the Trojans to

begin pushing the Achaians back to their ships.

It is during this time

that Hektor, a prince of Troy and the foremost warrior of the Trojans,

begins gaining ascendancy over the battlefield.

Hektor and the Trojan

allies nearly destroy the Achaians when Achilles allows his companion,

Patroklos, to defend the Achaian ships.

-

Once Patroklos enters the

battle, he over-confidently chases the Trojans back to the walls of

-

6

Troy, where he is killed by Hektor.

Achilles then reenters the fighting

to avenge Patroklos and kills several Trojans, including Hektor.

The

text of the I I iad ends when Achilles ransoms the body of Hektor to

Priam, Hektor's father and the king of Troy.

Achilles is killed in battle

a short while afterwards, and later in the tenth year Troy falls to the

Achaians with most of the heroes of Troy dead, and the civilian

population is divided up as slaves between the surviving Achaian

heroes, who then sail for home.

Most of the Achaian heroes,

however, either fail to return home safely, or suffer many set backs

in their attempt to re-establish themselves in their kingdoms that

they had left years earlier. 9

The Irish Tain begins

the Greek Iliad.

under

entirely

different

circumstances

than

The story recounted in the Iainactually begins in a

series of tales called remscel/a, that lead up to the opening of the Tain

with the invasion of Ulster by forces gathered by Medb, the queen of

Connacht.

The true beginning of the tale takes place in the bedroom

of Medb and her husband Ailill.

As Medb and Ailill list their

possessions, Medb realizes that she has no bull to equal the

magnificence of a white bull belonging to her husband.

Shortly

thereafter, Medb hears of a brown bull in the Kingdom of Ulster that

is more than the equal to the white bull of her husband.

After a failed

.t

Richmond Lattimore. (translator).

The Iliad of Homer.

p. 12-13 (Introduction).

-

7

attempt to purchase the brown bull from its owner, Medb decides to

take it by force.

With the aid of her husband, Medb musters troops

from every kingdom in Ireland, including a group of exiles from Ulster,

who are lead by Fergus, a former king of Ulster, and begins her

invasion.

Due to a strange curse leveled against the men of Ulster a

few generations earlier which causes them to suffer labor pains at

times of extreme crises, only the warrior Cuchulainn, whose name

means the Hound of Culann, is able to meet the invading forces.

However, Cuchulainn is able to single-handedly inflict heavy loses on

Medb's forces.

After their first few encounters with Cuchulainn,

Medb's husband Ailill asks Fergus "What sort of man is this Hound of

Ulster we hear tell of?"

Fergus responds by telling an account of

Cuchulainn's mac-gnimrada', which translates as "boyhood deeds."l0

For the next several days Cuchulainn killed at least one man during

the day, and at least one hundred each night.

Finally, Medb agrees to

a condition set by Cuchulainn that limited her troops to advancing

only while Cuchulainn was engaged in single combat with one of her

hand picked warriors.

Once that warrior fell, she was under

obligation to stop her advance until another warrior was sent to face

Cuchulainn.

Medb readily agreed to these terms, realizing that it was

better to lose one man each day than to lose a hundred every night.

-

10

Eleanor Knott and Gerard Murphy. Early Irish Literature. p.117.

-

8

After the arrangement has been made, a long series of single

combats

between various warriors and Cuchulainn follows,

Cuchulainn always winning.

with

Meanwhile, Medb is able to lead her

forces into the !heart of Ulster, plundering the countryside and

eventually stealing the great brown bull of Ulster.

When the series of

single combats proves to be too physically taxing for the wounded

and extremely exhausted CuchLilainn, the god Lug, who was generally

considered his father, comes to Cuchulainn and uses herbs to heal his

mortal son over the course of three days and nights.

When Cuchulainn

awakes, he discovers that the young boys of Ulster had come and

fought three battles against the invaders.

Although the young boys

killed three times their own number, they were all slain as a result.

This drives Cuchulainn into a battle madness and he kills a great

number of Medb's warriors.

The climax of the series of single combats soon follows when

Medb manages to seduce Ferdia, Cuchulainn's own foster-brother,

into facing Cuchulainn in single combat.

The battle between these

two great warriors takes three days of bloody fighting to complete

and is one of the most powerful scenes in epic literature.

Ultimately,

Cuchulainn is able to kill Ferdia by using his magical spear, the gae

-

bo/ga

11

•

After this battle, Cuchulainn suffered such massive wounds

" Thomas O'Rahilly. Early Irish History and Mythology. p. 58-75.

-

9

that he was unable to continue to fight until the last battle of the

Tain.

In the meantime, some single champions of Ulster came out to

face the hordes of invaders and while killing an honorable share of

opponents, they all were quickly brought down by Medb's forces.

Eventually, all the men of Ulster recover from their magically

induced illness and come out to repel the invaders.

The battle that

ensues is basically the kingdom of Ulster engaged in a battle with the

rest of Ireland.

At first, the battle seems to be going badly for the

men of Ulster since the invaders almost break their lines three times.

The tide of the battle quickly turns, however, once Cuchulainn is able

to overcome his wounds and retake the field.

Due to a prior

agreement, Fergus is obligated to retreat before Cuchulainn.

Once

Fergus has resigned from the battle, troops from the kingdoms of

Leinster and Munster also withdraw from the fighting.

The only

forces remaining on the field to oppose the Ulstermen were the nine

battalions of warriors from Medb's home kingdom of Connacht.

Cuchulainn and the men of Ulster defeated these battalions by night

fall, and Medb was forced to beg Cuchulainn to spare her life and the

lives of her remaining warriors.

Medb, however,

the great brown bull home to Connacht.

was able to send

Once the bull arrived there, it

and the great white bull belonging to Ailill began fighting, because

they both were actually rival magic entities.

The two bulls raged

-

10

throughout Ireland, ripping at each other, all night.

By the next

morning the brown bull of Ulster had killed the white bull of Connacht,

and began making its way back to its homeland in Ulster.

Upon

arriving at the boarder of its home pasture, the great bull fell dead.

The Tain then closes by saying that peace was made between

Connacht and Ulster, with the Connachtmen returning to their own

kingdom and the Ulstermen joining together in triumph at Emain

Macha 12 •

Clearly, there are textual similarities between the

lain.

lli.a.d. and the

In particular, both epics are primarily concerned with the

actions of a specific hero in an unusual and extremely stressful

situation, and, to a lesser extent, with the warriors and warfare in

general.

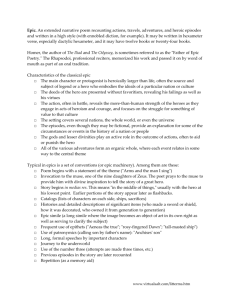

In an attempt to increase the understanding of such heroic

epics, many definitions of the term "hero" have been presented.

Several scholars have attempted to define the epic hero by citing a

list of characteristics which tends to be designed for, and more

applicable to, standard mythological heroes. These definitions

of "hero" have worked their way into standard usage, and are even

found in dictionaries with definitions such as "a mythological or

legendary figure endowed with great strength, courage, or ability,

favored by the gods, and often believed to be of divine or partly

-

12Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tajn. p. 52-253.

-

11

divine

descent.,,13 While this definition certainly applies to both

Achilles of the Achaians and Cuchulainn of the Ulaid, it nevertheless

remains merely a list of physical characteristics and potential

genealogies.

A better definition of an epic hero must avoid the

temptation to define a hero in terms of a list of attributes and origins,

and seek to reveal the true essence of what it means to be "heroic."

A definition that adequately suits this criteron is that an epic

hero consistently maintains his or her principle and defining loyalties.

Accordingly, epic heroes are often depicted as ultimately suffering

because of their inflexibility or because two or more of their loyalties

come into conflict.

This also provides an explanation for why so many

epic heroes eventually fall from ascendancy, being similar in nature to

the heroes of the tragic plays of Sophocles, who were often formerly

great men or women who have suffered an inescapable faW4.

However, this definition would still allow for the occasional

triumphant hero to succeed.

For instance, if the principle and defining

loyalty of Odysseus in the Odyssey of Homer is perceived to be the

procurement of a safe arrival home, then Odysseus is free to warp or

ignore any of his society's notions of what it is to be "heroic" and still

be a legitimate epic hero, regardless of the fact that neither of his

13 Philip Babcock Gove (editor-in-chief).

Webster's Third New International Dictionary of

the English Language Unabrjdged. p. 1060.

14 E.F. Watling. Sophocles; Electra and Other Plays.

(introduction). p. 8.

-

12

parents were divine or that he was in as much disfavor with Poseidon

as he was in the favor of Athena.

In more recent and perhaps more

radical example, Satan, in John Milton's Paradise

Lost. can readily be

defined as an epic hero if one considers that Satan maintains his

loyalty to perpetually rage against God and spread evil among God's

creations.

It is important to note that in order to make this definition of

epic hero function, the exact principle and defining loyalties of the

hero must be made clear.

For several heroes in the l.li.a.d. and the Tain,

the primary loyalty is to the maintenance of personal honor.

Achilles'

famous withdrawal from the war in Book I of the l.li.a.d. demonstrates

that he places a higher value on his honor than on the lives of his

fellow Achaians.

This point is stated expressly by Achilles before the

council of the Achaians in these lines from Book I of the

!..!la.d..:

And this shall be a great oath before you:/

some day longing for Achilles will come the sons

of the Achaians,/

all of them.

Then stricken at heart though you be,

you will be able/

to do nothing, when in their numbers before

-

man-slaughtering

Hektor/

13

they drop and die.

.heart

within

And then you will eat out the

youl

in sorrow, that you did not honour to the best of

of the Achaians.

(lines 239-244)15

Achilles does not exempt any of his comrades from his curse; in

fact, Homer uses the Greek word "sympantas", which translates as

"all together, or all in a body,,16 in line 241 to emphasize this fact.

When Patroklos is killed by Hektor after trying to save the other

Achaians from certain death by begging Achilles to lend him his armor

and to allow him to drive the Trojans back from the Achaian ships,

Achilles is partially responsible because it is his curse that is being

fulfilled.

In a later episode in the.L.l.i.ru!, Hektor demonstrates that he

values personal honor over the lives of his family and friends as well.

As Hektor stands before the walls of Troy about to face the enraged

Achilles, both his mother and father beg him to come inside the walls

of the city and ward off Achilles in relative safety.

Hektor, however,

is resolved to face Achilles, knowing that it may mean his death and

the destruction of his family and city, rather than suffer dishonor.

Hektor, thinking to himself in lines 108 through 110 in Book XXII,

-

15

16

Richmond Lattimore (translator). The Iliad of Homer. p. 65.

Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott (compilers). A English-Greek Lexicon. p. 1462.

-

14

states:

... and as for me, it would be much betterl

at that time, to go against Achilles, and slay him,

and come back,!

or else be killed by him in glory in front of the city.

Hektor can not divorce himself from the heroic code of honor that

demands that he meet Achilles on the battlefield in single combat to

the death, regardless of the devastating consequences.

Hektor

decides that an honorable death would be more acceptable than to

,-

commit the shameful act of protecting his city safely behind its

walls. 17 Obviously, among many of the heroes in the Iliad,

the

obligation to the maintenance of personal honor is held before all

other

loyalties.

Most of the heroes of the·

I.ai.n. also hold personal honor and glory

to be the defining essence of a hero.

The need to protect personal

honor for the heroes of the Ulaid is so fundamental that they are

willing to abandon practically all other social institutions for it.

In

one instance, the hero Cuchulainn was about to be married to the

beautiful Emer when someone mentioned that "this woman he has

-

brought here will have to sleep tonight with Conchobor -the first

17

James Hogan. A Gujde to the

Iliad. p. 273-274.

-

15

forcing of girls in Ulster is always his.tl18 The fact that his bride must

first sleep in the king's bed before coming to his own drove young

Cuchulainn into such a fury that the cushion beneath him burst up and

feathers flew about wildly.

The other Ulster warriors quickly realized

that the king could not accept the dishonor of not enforcing his own

edicts and that Cuchulainn would destroy any man who dishonored

him by having sex with his wife.

A compromise is reached when the

men of Ulster decide that Emer should sleep in Conchobor's bed that

night but with two men in between the two of them to "protect

Cuchulainn's

-

honour." 19 This story reflects the ability of the heroes to

make compromises when faced with conflicting loyalties; in this

instance the conflict is between loyalty to Ulster in the form of its

king and its laws and loyalty to protecting one's personal honor.

The

story also shows that while a compromise was agreed upon, both

Cuchulainn and Conchobor were willing to risk their lives and their

friendships among the men of Ulster to preserve their honor.

The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu, one of the remscella, or foretales,

of the Tain, however, presents a situation where a compromise

between loyalties could not be made.

The tragic story concludes with

Conchobor betraying a trust and having a band of warriors led by the

sons of Uisliu treacherously killed while under the direct protection of

-

18 Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tajn. p. 38.

19 lbid..

p. 39.

,-

16

Fergus and Conchobor's own son, Cormac.

As a result of Conchobor's

deceit, Fergus and Cormac, along with some other heroes of Ulster,

had to avenge the wrongful deaths of the sons of Uisliu in order to

protect their own honor.

Fergus and Cormac were driven to kill many

men and to burn the capital at Emain Macha, as a result of

Conchobor's deceit.

Once they had turned against Conchobor and the

rest of Ulster, Fergus and Cormac, along with three thousand other

men from Ulster, were

forced to seek refuge in the land of Connacht and later fought against

Cuchulainn and Ulster during the course of the

I.a.i.n20 • This story leaves

no doubt as to what is most important to them and where their

deepest loyalties lie.

Fergus leaves behind the land he loves and

Cormac turns against his own father, destroying his chances for royal

succession, because they feel that their honor has been insulted by

Conchobor.

Although maintenance and expansion of their own honor is the

primary loyalty for most of the heroes in both the II iad and the

~

there are secondary loyalties for different heroes in each epic.

The

most common secondary loyalty for the heroes in the

to family and close friends.

JJ..i.a.d. tends to be

Loyalty to the memory of Patroklos and

the guilt he feels for Patroklos' death is responsible for the incredible

20

lllld.. p. 14-15.

,-

17

change that comes over Achilles in the later books of the II jad.

Achilles, who has begun to realize the flaws and futility of the heroic

code, no longer cares for his curse, Agamemnon, or his own honor.

More than ever before, he has become alienated from the other

Achaians.

The fact that he makes it a paint to senselessly sacrifice

twelve Trojan nobles on the funeral pyre with the body of Patroklos21

shows that Achilles is only concerned with revenge and death.

Achilles' abandonment of honor as his primary loyalty is

reflected in several different passages, but one of the most powerful

in the .L.L.i.a..d. occurs once Achilles reenters the fighting to take revenge

for the death of Patroklos in Book XXI.

Achilles comes upon a young

Trojan prince whom he had captured twelve days earlier and sold into

slavery.

The young prince had managed to return to Troy through a

series of fortunate circumstances but had the misfortune of meeting

Achilles for the second time.

The young prince takes Achilles

by the knees and pitifully begs for his life again, but this time,

however, Achilles is not persuaded to grant mercy.

Achilles levies his

verdict with these cold words:

Poor fool, no longer speak to me of ransom,

nor argue it.!

21

Richmond Lattimore (translator). The Iliad of Homer. p. 455.

18

In the time before Patroklos came to the day

of his destiny!

then it was the way of my heart's choice to

be

sparing!

of the Trojans, and many I took alive and

disposed of them.

Now there is one who can escape death, if the

gods

send!

him against my hands in front of Ilion, not one!

of all the Trojans and beyond others the children

-

of Priam.

{lines 99-104)22

Another scene in the .L.li..ad. which

demonstrates a hero's

loyalty

to his family occurs in Book VI in an exchange between Hektor, his

wife Andromache, and their infant son.

Hektor has come inside the

walls of Troy during a decisive battle to ask the Trojan women to pray

and honor the goddess Athena so that she might grant the Trojans

victory over the Achaians.

Once inside the city he goes to his house to

see Andromache before returning to the fighting.

Hektor finds her on

the walls of Troy searching the battlefield for a sign that he is still

alive and well.

-

22lllli1. p.

After she and Hektor speak in one of the most

420-421.

-

19

endearing scenes in all of Western literature, Hektor reaches for his

baby son, who screams and shrinks back against his mother's breast

fearing his father's bloody bronze armor and the shining helmet with

it's long horse-hair crest.

Both Hektor and Andromache laugh as he

takes off the helmet, and then takes his son in his arms.

Hektor then

cuddles and kisses him before praying to the gods with these words:

Zeus, and you other immortals grant that this boy,

who is my son,!

may be as I am, pre-eminent among the Trojans,

great in strength, as am I, and rule strongly over

Ilion;!

and some day let them say of him: "He is far better

than

his

father,"!

as he comes in from the fighting; and let him kill

his

enemy!

and bring home the blooded spoils, and delight the

heart of his mother.

-

(lines 476-481 )23

With this prayer, Hektor reveals that he honestly hopes his son will

23.l12k1. p. 165-166.

-

20

surpass him in deeds and in honor, and while this sentiment may not

have been such an incredible admission for the heroes of the

lJ..i.a.d.., it

would be almost unheard of in the Tain.

In the story of the sons of Uisliu from the lain, Cormac took up

arms against his own people to avenge his father's insult to Cormac's

personal honor,

but in the story entitled "The Death of Aife's One

Son," the struggle between father and son over a matter of honor is

brought to a tragic crescendo.

Cuchulainn had fathered a son named

Connla by the warrior-queen Aife and left the instructions that she

was to send Connla to him when the child reached seven years of age.

He also told her to tell Connla that he must not reveal his name to

anyone, and that he should not make way for any man, nor refuse any

man in combat.

Seven years afterwards, Connla came to Ulster

looking for his father.

As his boat landed on Ulster soil, the Ulster

warriors sent one of their number down to meet him to ask him his

name and what business he had in Ulster.

True to the instructions

given to him, the boy refused to give any information about himself

and proceeded to march up the beach saying that he would not give

way to a hundred Ulster warriors.

A second hero of Ulster was sent to

stop the boy and make him pay for the insult to Ulster.

The young

boy, however, had much of his father's skill in battle and so he quickly

defeated the second warrior and tied him up with his own

-

21

sh ield-strap.

Finally, Cuchulainn, himself, came down and fought with

his own son because Connla had insulted Ulster, even though he was

merely following the instructions given to him by Cuchulainn.

However, rationality is no match for the incredible fury of Cuchulainn,

who advances on his son saying:

... the blood of Connla's!

body will

flush!

my skin with power!

little spear so fine!

,-

to be finely sucked

by my own spears!24

Obviously, Cuchulainn, and the heroes of the Tain in general, do not

appear to have the close sentimental attachments to their family as

Hektor and some of the other heroes in the.L.li.a.d..

Hektor cuddles and

kisses his baby son, while Cuchulainn stabs his seven year old son

with a magic spear so that it "brought his bowels down around his

feet. ,,25 The primary reason that Cuchulainn seems so heartless

towards his son is that Cuchulainn's loyalty to Ulster takes

precedence over any loyalty he feels towards his son.

Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tajn. p. 43-44.

25 1b.i.d.. p. 44.

24

Cuchulainn was

-

22

ready to destroy Conchobor, the king and therefore the embodiment

of Ulster, rather than allow Conchobor to dishonor him by sleeping

with his wife; and, in turn, Cuchulainn is more than willing to destroy

his only son in an attempt to avenge an insult to Ulster.

One reason why Cuchulainn places such an emphasis on the

honor of Ulster is because he can not divorce himself from Ulster.

Although Cuchulainn's commitment to personal honor still overrides

his dedication to Ulster, he never completely isolates his own identity

from the abstract entity that is Ulster, which includes the warriors,

the soil, the culture, and the almost spiritual aspect of Ulster.

This

helps to explain why Cuchulainn does not feel alienated while he is

camped all alone in the middle of a wilderness, single-handedly

holding back the huge force of invaders lead by Medb.

On the other

hand, Achilles feels completely isolated and alone at Troy after his

quarrel with Agamemnon, even though his ship and tent are part of

one of the largest collective forces of the Achaian people ever.

This

sense of alienation further increases after the death of Patroklos

until funeral games held in the fallen warrior's honor26.

If the definition of epic hero is taken as meaning a character in

an epic who maintains his principle and defining loyalties, as opposed

to the current popular definition, which is based on a collection of

-

2e

James Hogan. A Gujde to the Iliad. p. 243.

-

23

attributes,

additional analysis of the primary and

secondary

loyalties

each of the major heroes in both the Iliad and the Tain could be

compiled in order to provide a deeper understanding of each

character, as well as each epic as a whole.

Once a particular

hero's loyalties have been charted, his or her motivation and internal

workings in each scene should be rendered more apparent.

However,

certain characters in both the Iliad and the I..ai.n can not be defined as

epic heroes since they do not maintain their primary loyalties.

In the

ill.sui. for instance, Agamemnon never formulates a defining loyalty

since he takes Achilles' war prize in Book I to maintain his personal

-

honor 27 , but later, in Book IX, he offers to give the prize back along

with several other prizes from his own collection in an attempt to

bribe Achilles to rejoin the fighting2B.

Clearly, Agamemnon does not

maintain a primary loyalty, and therefore could not be considered a

true hero of the epic, but instead he is merely a major character

within the narrative of the poem.

Similarly, in the I..ai.n, Ferdia, the

foster-brother of· Cuchulainn, can not be considered an epic hero.

When Medb first summons Ferdia to her tent, he knows that it would

not be honorable to fight Cuchulainn since they were sworn fosterbrothers.

However, he allows himself to be seduced by Medb and

agrees to fight Cuchulainn.

-

Ferdia, whose primary loyalty should be

Richmond Lattimore (translator). The Iliad of Homer.

28 l12id..

p. 201-206.

27

p. 67-68.

-

24

to personal honor, finds himself in a hopeless situation once he has

said he would meet Cuchulainn in battle, since it would be just as

dishonorable to attack his foster-brother and

break his warrior's

bond and oath of brotherhood as it would be to break his oath to

Medb to fight Cuchulainn 29 •

Thus, while Ferdia is certainly a tragic

figure in the Tain, he dies not as a true hero but as one who has fallen

from the path of the true epic hero.

Ferdia's tragic loss of his status as a hero comes as a result of

Medb's words and actions as a classic epic seductress,

persuades

"into

disobedience,

disloyalty,

or

a woman who

desertion."30 An epic

seductress then is a woman who draws epic warriors away from their

primary loyalties.

Most would agree that, in the story of the Trojan

War, Helen acts as a seductress when her beauty entices Paris to defy

the rules of the guest-host relationship and causes him to

dishonorably steal her off to Troy.

Likewise, in the Tain, Medb acts as

the epitome of the seductress when trying to get Ferdia to fight

against Cuchulainn by saying she would give Ferdia the following

things:

... a chariot worth three times seven bondmaids,

-.

Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tain. p. 168-170.

30 Philip Babcock Gove (editor-in-chief).

Webster's Third New International Dictionary Qf

the English Language Unabridged. p. 2054.

:IV

-

25

with warharness enough for a dozen men, and a

portion of the fine Plain of Ai equal to the Plain

of Murtheimne.

Also the right to stay in Cruachan,

with your wine supplied, and your kith and kin free

forever from tax and tribute.

And this leaf-shaped

brooch of mine that was made out of ten score

ounces and ten score quarters of gold.

And

Finnabair, my daughter and Ailill's, for your

wife.

And my own friendly thighs on top of

that if needs be. 31

Medb does not stop at bribery, but also lies to Ferdia telling him that

Cuchulainn has previously insulted him, and Ferdia eventually

succumbs to Medb's will.

In this instance, Medb demonstrates that

the role of the seductress is not limited to sexual enticement,

although she maintains that as part of her role, but the true

seductress is free to use any tactic or means necessary, including

bribery and lying, to get her victim to fall into disloyalty32.

Although there are several instances of the classic and often

stereotypical seductress in epic literature, there is another category

of seductresses in epic that differs primarily from their more

--

Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tain. p. 169.

32 Moyra Caldecott. Women in Celtic Mythology.

p. 167-168.

31

-

26

traditional counterparts in that they often fail in their attempt to

seduce.

good-wife.

This category contains the idea of the seductress as the

Often in epic the wife of a hero tries to seduce her

husband from what he considers his primary loyalty.

The good-wife's

reason for the seduction tends to be noble, caring, and rational.

instance, in the

For

.lli.w1, when Hektor meets his wife Andromache on the

walls of Troy in Book VI, she begs him to fight off the Achaians from

inside the walls where it would be much safer.

Through her tears, she

pleads with Hektor to do her bidding and not to leave their son an

orphan and herself a widow.

Hektor is deeply moved and tells her

that he worries more about her future after his death than he does

for the safety of his own parents or the preservation of the city, but

he maintains his primary loyalty to personal honor.

He tells her that

he would be shamed before his people and that his spirit drives him to

fight as a hero on the battlefield 33 •

While Andromache does attempt

to seduce Hektor from his duty, she certainly holds no malice or deceit

in her heart for him, but rather is deeply concerned about the welfare

and well-being of her young husband.

Andromache, then, succeeds in

being a good-wife to Hektor, in part because she attempts, but fails,

to persuade Hektor to give up his loyalty to his honor.

In the Tain. Emer, Cuchulainn's wife,

33

also proves herself to be a

Richmond Lattimore (translator). The Iliad of Homer. p. 163-165.

-

27

good-wife through a well-intended but failed attempt at seduction.

In the story of "The Death of Aife's One Son," when Cuchulainn was

storming down the beach to destroy his son Connla for insulting

Ulster, Emer tries to stop him.

She quickly recognizes Cuchulainn's

own son, even though he had been born to another woman, and places

her arm around her husband's neck and tries to restrain him with

these

words:

Don't go down!!

It is your own son there/

don't murder your son/

the wild and well born/

son let him bel

is it good or wise/

for you to fall/

on your marvellous son/

of the mighty acts/ ...

if Connla has dared us/

he has justified it.!

Turn back, hear me!!

My restraint is

-

reason/

-

28

Cuchulainn

hear itl ... 34

Cuchulainn, however, is not persuaded.

Unlike Hektor who was gentle

and sympathetic with Andromache, Cuchulainn responses to his wife's

plea for restraint and mercy by answering her harshly with these

words:

Be quiet, wife.!

It isn't a woman/

that I need now/

to hold me back/

in the face of these feats

and

shining

triumph/

I want no woman's /

help with

victorious

my work/

deeds/

are what we need/

to fill the eyes/ ... 35

Cuchulainn ends his response to Emer by clearly stating, "No matter

34

Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tajn. p. 42-43.

35

lllld.. p. 43.

-

29

who he is, wife, I must kill him for the honour of Ulster.,,36 Emer

realizes that her husband is resolved to meet his own son in combat

because he must not allow Ulster to be insulted, and so she remains

silent while Cuchulainn first tries to drown his son and then finally

eviscerates him.

Although Emer may initially seem too passive, it is important to

emphasize her noble qualities, which make her a good wife by the

standards of epic literature.

Cuchulainn first came to court Emer as

she sat on the lawn in front of her father's fort with several other

young women working at embroidery.

He began speaking to her in

riddles to test her wit, but Emer had no trouble discovering

Cuchulainn's hidden meaning and answering with a few riddles of her

own 37 .

Cuchulainn, while staring at Emer's breasts over the top of her

dress, said "I see a sweet country, I could rest my weapon there."38

Emer replied by saying no man would travel in that country until he

had managed to complete several nearly impossible feats of strength

and warrior's skill.

Ultimately, Cuchulainn has to go off to a magic

island to get additional training before he can complete the tasks that

Emer has set before him.

Before Cuchulainn leaves, however, he

and Emer took a vow of faithfulness to each other until he returned or

36.l.bk1. p. 44.

37

Moyra Caldecott. Women in Celtic Mythology. p. 95-98.

36 Thomas Kinsella (translator). The Tain. p. 27.

.-

30

until one of them died.

It is interesting to note that Emer protected

her own interests by adding that the vow would be invalidated upon

either one of their deaths, since Cuchulainn was setting out on a

dangerous journey while she remained in relative safety.

Emer is

presented as being an excellent wife for an epic hero in Cuchulainn's

courtship of her, because she encourages and expects him to act

heroically.

Although Emer occasionally attempts to get Cuchulainn to

act in a manner that he considers contrary to his primary and

secondary loyalties, she always speaks with concern, often acting as

the voice of moderation in the mist of over-inflated male egos.

Emer

also aids Cuchulainn in his quest to preserve and increase his status

among the men of Ulster. She would not take Cuchulainn as her

husband until he had received all the training he would need to

become the greatest hero in Ireland.

It could easily be said that

Cuchulainn could not have reached the pinnacle of fame and skill

without Emer's wit,

reason,

and encouragement.

Oral epic literature, including the Iliad and the Tain, is able to

provide a key inSight into each work's parent culture through the

creation of the roles of the hero, seductress, and good wife.

Although there are several examples in the !!.l.aQ. and the Tain of

females who definitely act heroically, as well as males who seduce, it

is necessary to maintain a general focus on the male hero and the

-

31

female seductress in order to clearly establish the relationship and

the fundamental

differences between the traditional

definitions of the terms "hero" and "seductress."

and

the

revised

In the revised

definitions, these roles can be understood in terms of their

interactions with each other.

The true epic hero will consistently

maintain his primary loyalty regardless of the words and actions of

other heroes, seductresses, or even his own spouse.

The true

seductress in epic succeeds at seducing a hero from his loyalties and

bending that person to his or her will, thereby destroying the hero's

status as a hero.

A good wife often attempts to seduce her spouse,

but never maliciously and always with his best interest at heart.

The

seductress acting as a good wife also tends to fail to dissuade her

husband from his chosen course.

These revised definitions not only enrich the understanding of

the epic characters themselves and the epic as a whole, but they also

have the ability to effect a deeper understanding of the value system

of the parent culture.

By examining the evidence as it was presented

throughout the various quotations, some logical inferences can be

made about the worldview of the people who originally constructed

and circulated the epics.

While personal honor is the primary loyalty for many of the

heroes of both the

l.li.a..d.. and the Iain., there seems to be a difference

32

between the two groups of heroes concerning their secondary

loyalties.

The heroes of the II i ad tend to maintain a secondary loyalty

to their families and close friends, while the Ulaid uphold the kingdom

of Ulster as their secondary loyalty.

These differences in secondary

loyalty reflect the fact that the Greek heroes of the

!.!l.a..d.. are

presented as being only loosely allied with each other under the

unsteady

leadership

of Agamemnon,

with

each

aristocratic warrior

maintaining his strongest political ties to his own predominantly

autonomous kingdom.

In the Irish tradition, however, all the

members of the Ulaid conceptualize themselves as being part of the

same single kingdom throughout the course of the Tain.

The way each

society is politically and socially organized within each epic aids in

granting a deeper insight into the methods of social organization

practiced by each of the epics' parent cultures.

The role of the seductress also exhibits a dimorphism between

the II i ad and the Iain.

Helen, the Greek seductress, relies exclusively

on her sexuality to seduce the warriors from their individual loyalties,

and is thereby limited in the type of interaction and control that she

may have with the other characters in the epic.

In the Iain,

however,

Medb is not only a seductress without limitations on her means to

seduce, she also dresses in armor, leads men into battle, and openly

-

engages male warriors in battle.

Similarly, in the Iliad. Andromache's

-

33

character is largely centered on her dependence on Hektor, while

Emer's character in the

I..aln is far more complex.

Even though she is

only depicted in regards to her relationship with Cuchulainn, she is

never depicted as being solely dependent upon him for support and is

far more quick to challenge his position within their relationship than

Andromache, who seems complacent by comparison.

By examining

the roles of these four women within the context of their respective

epics, it would seem clear that aristocratic women generally held a

higher status in ancient Irish society and claimed more social and

political

freedoms

than

their

Greek counterparts.

The study and analysis of ancient epic is nearly as old as the art

of epic poetry itself.

This long tradition of scholarship has been, and

still needs to be, perpetually examined and revised.

In the modern

world the terms "hero," "heroine," "seducer," and "seductress"

have

a hallow, archaic sound, and the abstract notions incorporated into

each of these roles are largely viewed as being irrelevant.

These

roles, however, are part of the Western World's intellectual birth and

remain at the primal heart of everyone.

-

WORKS CITED

Amos, H.D. and A.G.P. Lang. These Were the Greeks.

Springs, Pennsylvania: Dulfour Editions, 1982.

Caldecott, Moyra. Women in Celtic Myth.

Destiny Books, 1988.

Chadwick, H.M. The Heroic Age.

Press, 1926.

Rochester, Vermont:

London: Cambridge University

Dillon, Miles. Early Irish Literature.

Chicago Press, 1948.

-

Chester

Chicago: University of

Dinneen, Patrick, compiler and editor. An Irish-English

Dublin: Educational Company of Ireland, 1934.

pictionary.

Gove, Philip Babcock, editor in chief. Webester's Third New

International

Dictionary.

Springfield, Massachusetts:

G. & C. Merriam Company, 1959.

Hogan, James C. A Guide to the Iliad.

Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1979.

Garden City, New York:

Hull, Eleanor. The Cuchulljn Saga in Irish Literature. London:

David Nutt in the Strand, 1898.

Kinsella, Thomas, translator.

The Tain.

Irish University Press Inc., 1969.

Knott, Eleanor and Gerald Murphy. Early

York: Barnes and Noble, 1966.

-

White Plains, New York:

Irish

Literature.

New

Lattimore, Richmond, translator.

The Iliad of Homer. Chicago:

The University of Chicago Press, 1951.

Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott.

Greek-English

Lexicon.

8th Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1901.

O'Rahilly, Thomas F. Early Irish Hjstory and Mythology. Dublin:

Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1984.

Watling, E.F., translator. Sophocles: Electra and Other Plays.

London: Penguin Books, 1953.

-

Other

Works

Consulted

Chadwick, H. Munro and N. Kershaw Chadwick. The Growth of

Lite ratu re. Volume I. The Ancient Literatures of Europe.

Cambridge: University Press, 1932.

Chadwick, Nora Kershaw.

Books, 1970.

The Celts.

Middlesex, England: Penguin

Dillon, Myles and Nora K. Chadwick. The Celtic Realms. London:

Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1967.

Fagles, Robert, translator. The Iliad.

1990.

Fitzgerald, Robert, translator.

Books, 1961.

Gantz, Jeffrey.

1981.

New York: Penguin Books,

The Odyssey.

Early Irish Myths and Sagas.

Jacksan, Kenneth Hurlstone.

Books, 1971.

New York: Vintage

London: Penguin Books,

A Celtic Miscellany.

Lady Gregory. Cuchulain of Muirthemne.

University Press, 1970.

London: Penguin

New York: Oxford

MacCary, W. Thomas. Childlike Achilles: Ontogeny and Phylogony

in the Iliad. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost. a Poem in Twelye Books. Edited by

Merritt V. Hughes. New York: Odyssey Press, 1962.

Monaghan, Patricia. The Book of Goddesses and Heroines. St. Paul:

Llewellyn, 1990.

-

O'Conner, Frank. A Short History of Irish Literature: A Backward Look.

New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1967.

o hOgain,

Daithi. The Hero in Irish Folk History. Dublin: Gill and

MacMillan, 1985.

Ross, Anne. Druids. Gods. and Heroes from Celtic Mythology. New

York: Schocken, 1986.

Sjoestedt, Marie-Louise.

Gods and Heros of the Celts. Translated by

Miles Dillon.

Berkeley, California: Turtle Island Foundation, 1982.

-

-