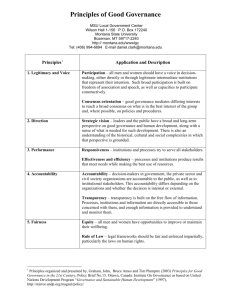

Human Flourishing Project Briefing Paper 4 Governance For Human Flourishing

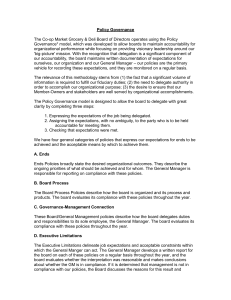

advertisement