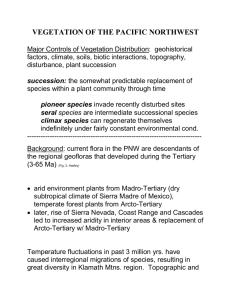

FIELD GUIDE FORESTED PLANT ASSOCIATIONS for

advertisement