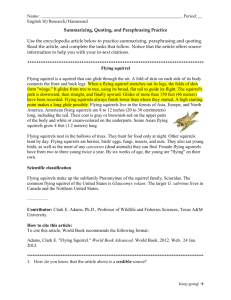

Maturation and Reproduction of Northern Flying Squirrels in Pacific Northwest Forests

advertisement