A Social History of Wild Huckleberry Harvesting in the Pacific Northwest

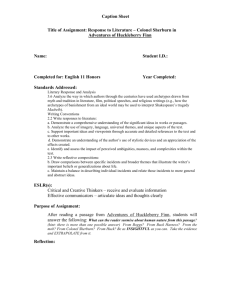

advertisement