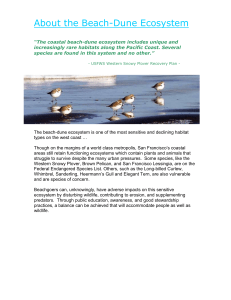

Assessing Management of Raptor Predation for Western Snowy Plover Recovery

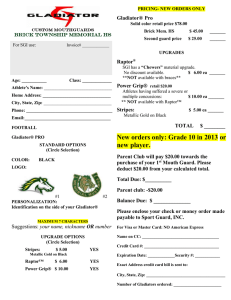

advertisement