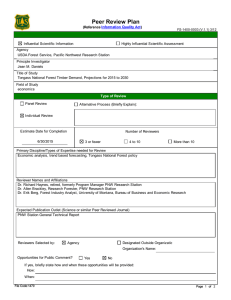

Tongass National Forest Timber Demand: Projections for 2015 to 2030

advertisement