A TIME FOR CHANGE? Consulting Communities on a

advertisement

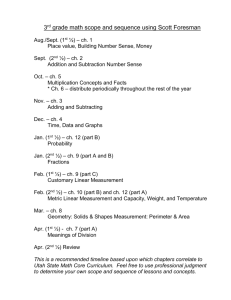

A TIME FOR CHANGE? Consulting Communities on a Draft Land Code in Chad 1 Acknowledgements and background Written by Stephanie Gill (Tearfund UK) and Jocelyn Madjenoum (Independent Researcher, Chad). © Tearfund, 2015 Photo credits: Boniface Tchingweube, EEMET With thanks to: Levourne Passiri, Boniface Tchingweube and Tearfund partners EEMET, PCAR, SCMR and CECADEC. Tearfund: Tearfund is a UK-based Christian relief and development agency working with a global network of churches to help eradicate poverty. Tearfund supports local partners in more than 35 developing countries and has operational programmes in response to specific disasters. EEMET: (l’Entente des Eglises et Missions Evangeliques au Tchad – the Accord of Churches and Evangelical Missions in Chad) is a partner of Tearfund. EEMET is an umbrella organisation representing different Christian denominations. It undertakes development work in different parts of Chad, in areas including food security, education, HIV, work with orphans, and peace and reconciliation. It undertakes advocacy on these issues from a local to national level. Tearfund partners EEMET, PCAR (Programme Chrétien d’Animation Rurale – Christian Programme for Rural Development), SCMR (Service Chrétien en Milieu Rural – Christian Service in Rural Communities) and CECADEC (Centre Chrétien d’Appui au Développement Communautaire – Christian Center Community Development Support) have all been involved in advocacy on land issues for many years. In January 2014 Tearfund facilitated a workshop in N’Djamena that brought these partners together to discuss how they might jointly scale up their advocacy on land rights. Following this workshop, representatives from these partners, along with Tearfund staff, met with the General Secretary from the ministry responsible for land. The General Secretary presented them with the draft of a new land code and requested constructive feedback. This research was undertaken in response to this request. This research consisted of four community consultations, each coordinated where one of Tearfund’s partners is primarily based. All areas face annual conflicts between pastoralists and farmers. The research findings presented in this report were funded by Tearfund and coordinated by EEMET. EEMET appointed Jocelyn Madjenoum, a consultant from Chad, to undertake the research.1 This report presents a summary of EEMET’s research with permission granted by EEMET. This report also contains some additional input for the purposes of clarification and background information. This came from further discussions with staff, partners and existing literature. 1 2 To access EEMET’s report please contact Stephanie.Gill@tearfund.org Table of Contents Acknowledgements and background 2 Executive summary 4 Introduction 9 Introduction to Chad 9 Background to Chadian land policies 9 Methodology Research aim 11 Research questions 11 Research methodology 11 Limitations to research 12 Analysis and Results 3 11 13 Customary rights 13 Expropriation and eviction 15 Missing aspects 18 Potential loophole 19 Conclusion 20 Recommendations 22 Bibliography 23 Executive summary BACKGROUND This research aims to critically evaluate the current draft of a new land code in the Central African country of Chad. In January 2014, the government of Chad presented Tearfund and four of Tearfund’s partners with a draft of the proposed new land code and requested constructive feedback. Research was undertaken in response to this request and is presented here. The aim of this research is to ensure the new law gives fair consideration to the rights of those who depend on the land for their livelihoods – approximately 80% (USAID 2010) of the current 12.83 million population in Chad (World Bank 2013). The current land law has not been updated since 1967 and, according to USAID (2010), ‘does not reach critical issues of land tenure’ (p 3). The majority of the Chadian population are unfamiliar with the content of these laws and they are not available in local languages. Customary land tenure systems are used by most landholders in Chad. This presents the challenge of an uneasy coexistence between state and customary law, which often puts communities at a disadvantage, especially regarding ownership of land and eviction procedures. Revising this land law presents an opportunity for these issues to be addressed. RESEARCH QUESTIONS Building on a review of background information and existing literature, this work aimed to examine three core sets of research questions: 1. Does the proposed new land code recognise customary rights, and what provisions does the law make with regards to eviction and compensation? 2. Are there any important aspects that are missing or loopholes which could potentially have a negative impact on communities? 3. How well does the proposed new land law match up to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ ‘Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (FAO Guidelines)’? 4 METHODOLOGY Initial issues for clarification, discussion and consultation were identified through a preliminary overview of the proposed new land code, drawing on legal expertise from the UK and Chad. A series of consultation meetings were then organised with a range of stakeholders from local communities in three regions across the country: Béré, Pala and Bousso. This was followed by a workshop in N’Djamena in order to discuss the recommendations put forward through the community consultations. Figure 1: Map showing location of consultations and workshop. Semi-structured interviews were also held with civil society organisations and government officials during the process. Overall around 130 participants were consulted with. RESULTS Clarification required The draft code appears to recognise customary rights and goes some way towards protecting them. However, concerns were raised at the lack of definition of customary rights and further clarity could offer communities greater protection. The code seeks to allow customary rights to be changed into property rights, although farmers have to prove that they possess and use the land. The intention and rationale behind this may be promising, but, without clearer guidelines, how this is implemented in practice could present challenges. Further clarity is also required for the conditions in which the varying levels of government can allocate different plot sizes. In addition, the draft code states that people can be expropriated when ‘public interest’ requires this. However, without a clear definition of ‘public interest’, multiple interpretations may arise in practice. 5 Obtaining a land title It is not clear whether the draft code will improve the existing process of obtaining a land title. Registering land ownership under the current law requires ‘six procedures, an average of 44 days, and payment of 23% of the property value’ (USAID 2010 p 6), and participants in the consultation expressed frustration from their experiences of this process. Under the new code, this procedure should be simplified, the services responsible should be decentralised, and the cost of obtaining a land title should be reduced. This would enable a greater number of holders of customary rights to obtain an official land title and could give them greater bargaining power in the process of obtaining compensation when faced with expropriation or eviction. Figure 2: Local authorities at the consultation in Béré. The expropriation process Concerns were raised about the expropriation process laid out in the draft code. The code states that once a declaration has been made that a piece of land is required for ‘public interest’, the owner is forbidden from undertaking any construction on the land. This potentially puts the owner of the land at a significant disadvantage while they wait for the expropriation procedure. Additional concerns raised included the potential costs incurred by the farmer in the appeal process, the failure to take into account loss of future earnings in determining compensation, and the relatively low notice period (one month) to evacuate a building once the process is finalised. Figure 3: Consultation held in Bousso 6 Local mediation One aspect participants considered to be missing from the land code is a provision for settling land disputes using mediation techniques at a local level. Participants also felt that having one land code that is supposed to be applicable to both rural and urban contexts may put some communities at a disadvantage. FAO Guidelines The draft code goes some way towards aligning itself with the principles of the FAO Guidelines, however alignment could be strengthened in a number of areas, including eviction and expropriation processes and local level mediation. CONCLUSION This draft code has the potential to benefit the 80% of Chadians (USAID 2010) who depend on land for their livelihood, though improvements and amendments are required, as outlined above. It is critical that due care is taken for the law to be implemented effectively. It will be of paramount importance that rural farmers are made aware of their rights under the proposed new law – both rights that are remaining and new rights. It will be particularly important to consult with women’s groups; though the draft code itself does not discriminate based on gender, there may be challenges implementing this principle at a local level. It is important to recognise that 63% of the Chadian population are illiterate (World Bank 2012) and that additional tools are required to raise awareness. In order to address these challenges and aid the implementation of the land code in rural areas, a rural land service should be established at the sub-prefecture level with the purpose of specifically addressing the land needs of rural communities. Questions remain about whether sufficient funding has been allocated to the implementation of the proposed new land law once it is passed. The international community will have a significant role to play in supporting the government of Chad in this process. Finally, further research should be undertaken to enable a wider participation of stakeholders, ensuring greater diversity of input into the formation and implementation of this proposed new law. 7 RECOMMENDATIONS Based on this research on the draft land code, the following recommendations are presented: 1. For clarification: The term ‘customary rights’ must be clearly defined. The definition of ‘permanent and evident’ ground coverage must be clearly defined. The term ‘public interest’ should be clearly defined. Clarification is required for the conditions by which the Council of Ministers can allocate land over 10 hectares. 2. For amending: The process for obtaining land titles should be simplified and the costs significantly reduced. The article forbidding any construction, planting or improvements on land during the expropriation process will put the owner of the land at a significant disadvantage and should be revised. Loss of future earnings should be taken into consideration as part of compensation. A longer notice period (than one month) should be given once the compensation ruling is finalised. 3. For further consideration: The articles outlining the consultation process (which occurs prior to any compulsory purchases) should be further developed. The expropriation process must not be drawn out and costs of appeal should be covered by the state. The state must ensure it has sufficient funds to effectively implement this law (including the expropriation costs) effectively. 4. For provisions to be added: The code should contain articles specific to rural land and articles specific to urban land. A provision should be included that supports mediation as a mechanism for resolving land-related disputes. 5. For implementation: Community participation is absolutely essential for the development and implementation of this code and further research should be undertaken to help strengthen it. Communities must be made aware of their rights under the code – both remaining and new. Local officials must be trained to help implement them. A rural land service should be established at the sub-prefecture level. Sufficient funding must be in place for all areas required to implement this code effectively 8 Introduction Introduction to Chad Chad is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 184 out of 187 countries in the 2014 UN Human Development Index. Chad’s population of 12.83 million (World Bank 2013) faces challenges sadly familiar to the Sahel region, including the impacts of climate change, population growth, poor governance, food insecurity, land degradation, and internal and external conflict. It also has the lowest life expectancy and the highest under five mortality rate out of Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Mauritania (WHO 2014). Around 80% of Chad’s labour force is in the agricultural sector (USAID 2010) so access to and sustainable use of land is a critical issue. Background to Chadian land policies ‘The country’s skeletal land legislation dates from 1967 and does not reach critical issues of land tenure’ (USAID 2010 p 3). The main land legislation for Chad is contained in three laws from July 1967 (Laws No. 23, 24 and 25). The majority of the Chadian population are unfamiliar with the content of these laws and they are not available in local languages. Customary land tenure systems are used by most landholders in Chad. This system contributes to an uneasy coexistence between state and customary law which has many implications, including making obtaining title deeds challenging. The 1967 laws require landholders to register land and stipulate that without title deeds the land is state land. This clause overrides the customary land tenure systems. However, the registration process is complex, inaccessible, expensive, and not only out of reach for most smallholder farmers, but also largely unknown to them as well. As a result, very few land titles have been issued, especially in rural areas. The formal laws also state that if a landholder does not use their land for ten years, then they lose their right to it. This clause demanding evidence of use can be challenging to verify. The 1967 laws also outline the state’s right to carry out expropriation. One of the disadvantages of lack of understanding of the law is that communities do not understand their land rights during the expropriation process. Many communities that Tearfund’s partners work with have been directly impacted by this process and have been forced to vacate their land, with little, if any, compensation provided. A frequent reason cited for land expropriation is the arrival of extractive companies – mainly mining for gold and uranium. Another reason cited is the expansion of towns and villages forcing rural farmers off their land. 9 Disputes over land are an increasingly common problem, particularly between farmers and pastoralists. Partners cite conflicts between farmers and pastoralists to be an annual challenge in the areas in which they work, with loss of life occurring most years. Conflicts have also occurred when people are evicted from their land with little or no compensation. The main official channel for settling conflicts is through the courts; however, few, if any, are accessible locally. There are also customary authorities who mediate between conflicting parties to varying degrees of effectiveness. 10 Methodology Research aim To ensure that the new land law gives fair consideration to the land rights of smallholder farmers who depend on land for their livelihoods. Research questions Building on a review of background information and existing literature, this work aimed to examine three core sets of research questions: 1. Does the proposed new land law recognise customary rights and what provisions does the law make with regards to eviction and compensation? 2. Are there any important aspects that are missing or loopholes which could potentially have a negative impact on communities? 3. How well does the proposed new land law match up to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ ‘Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (FAO Guidelines)’?2 Research methodology Initial issues for clarification, discussion and consultation were identified through a preliminary overview of the proposed new land law, drawing on legal expertise from the UK and Chad. A series of consultation meetings were then organised with a range of stakeholders from local communities in three regions across the country: Béré (where SCMR is based), Pala (where CECADEC is based) and Bousso (where PCAR is based). The consultations had two purposes: 1. Inform communities of the draft land code 2. Obtain feedback to the draft code, including concerns and proposed amendments. This was followed by a workshop in N’Djamena (where EEMET is based) with a range of stakeholders. The purpose of this workshop was threefold: 1. Inform the participants of the draft land code 2. Provide feedback on the draft law 3. Discuss the recommendations put forward through the community consultations. Semi-structured interviews were also held with civil society organisations and government officials during the process. Overall around 130 participants were consulted with. As far as possible the following groups of stakeholders were consulted with during each consultation: elected representatives, farmers, pastoralists, women leaders, religious leaders and local leaders. 2 ‘The Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security’ promote secure tenure rights and equitable access to land, fisheries and forests as a means of eradicating hunger and poverty, supporting sustainable development and enhancing the environment. They were officially endorsed by the Committee on World Food Security on 11 May 2012. 11 Figure 4: Map showing location of consultations and workshop Limitations of research Limitations to this research included the following: A relatively small number of people were consulted (around 130 in total). Consultations occurred in the south of Chad and were limited to the location of Tearfund partners. It was challenging to get an equal spread of stakeholders at the consultations and therefore ensure that they each had an equal opportunity to input. 12 Analysis and results This analysis draws out the common themes that emerged through the background research and community consultations. Analysis of the first two research questions regarding (i) customary rights, expropriation, eviction and compensation and (ii) missing aspects and loopholes, are discussed in turn. The third research question regarding the FAO Guidelines is discussed throughout. The research recommendations are presented during the analysis and then grouped together at the end of this report. Customary rights The term ‘customary rights’ must be clearly defined. The draft code appears to recognise customary rights. Articles 9 and 24 of the draft code state that the owners of customary rights may continue to enjoy them. Article 24 goes further to state that those with customary rights may continue to enjoy them if they do not have to be expropriated under Article 103. Concerns were raised at the lack of definition of customary rights given in the draft code. Article 24: Recognised rights for holders of customary rights All physical and moral persons holding customary rights before the publication of the present law will retain them. In consideration of common public interest, the State or local and regional authorities may dispossess them in accordance with article 103 and the articles of the present law. Article 70 appears to go some way towards protecting the holders of customary rights. It is therefore important that this definition is not open to misinterpretation, and therefore further clarity could offer communities greater protection. Article 70: Conditions of transfer or modification of customary land rights Customary land rights, whether collective or individual, may not be transferred or modified in favour of corporate bodies or individuals who may have the same rights due to customary rules, and only within the limitations and conditions that these provide. Evidence of this possession should be established by all means possible. Sections 9.5, 9.8 and 10.6 of the FAO Guidelines are explicit in their call for the state to protect those with customary rights, with section 9.8 stating ‘States should protect indigenous peoples and other communities with customary tenure systems against the unauthorised use of their land’ and section 10.6, which states, ‘where it is not possible to provide legal recognition to informal tenure, States should prevent forced evictions’. The language of the code could be strengthened to reflect this. 13 The definition of ‘permanent and evident’ ground coverage must be clearly defined. Article 71 seeks to allow customary rights to be changed into property rights. It states that this is possible when there is ‘permanent and evident’ ground coverage, or rather ‘evidence of permanent possession’. Article 71: Conditions for changing customary rights in property law Customary rights, whether exercised collectively or individually, may be changed into property rights when they comprise permanent and evident ground coverage. The intention and rationale behind this article may be promising, but how this article is implemented in practice could present challenges without clear guidelines as to how a land owner proves that they possess and use the land. It is therefore important that a clarification of what is meant by ‘permanent and evident’ ground coverage is given in order to avoid abuse or misinterpretation by the authority responsible for issuing these rights. The process for obtaining land titles should be simplified and the costs significantly reduced. Article 8 outlines that a person holding customary rights is entitled to register their land and obtain a legally recognised land title. Article 8: Heritage composition for other natural or legal persons The land heritage of other persons or entities includes all real estate held by them by virtue of a land title transferred to their name as a result of the conversion of a customary right or concession right as registered ownership, assignment or other transfer mode of a land title. The significance of a land title is highlighted in Article 85, which lays out the binding nature of a land title and states that it cannot be overwritten by another form of land title. It assures ownership of land for the holder of the land title. Article 85: On the lasting and irrevocable nature of a land title and rights granted The land title is lasting and irrevocable. It forms, where applicable, the unique basis for all existing property rights, before all courts. From the date of registration, no property right, no ground for rescission or cancellation by reason of prior ownership may be claimed against the current owner or their successors. Some land titles arising as the result of a grant may, however, include a cancellation clause or a transfer restriction clause when issued; such clauses are always temporary. However, it is not clear whether the draft code will improve the existing process of obtaining a land title. Registering land ownership under the current law requires ‘six procedures, an average of 44 days, and payment of 23% of the property value’ (USAID p 6), and participants in the consultation expressed frustration from their experiences of this process. This procedure should be simplified, the services responsible should be decentralised, and the cost of obtaining a land title should be reduced. This would enable a greater number of holders of customary rights to obtain an official land title and could give them greater bargaining power in the process of obtaining compensation when faced with expropriation or eviction. The FAO Guidelines also support ‘simplified procedures and locally suitable technology to reduce the costs and time required for delivering services’ (Section 17.4). 14 Expropriation and eviction The term ‘public interest’ should be clearly defined in the code. The draft code states in articles 103 and 128 that people can be expropriated when ‘public interest’ requires this. Article 103 refers to people with title deeds and 128 to those with customary rights. Article 103: Compulsory purchase Compulsory purchase is the procedure by which the public authorities require a legal or physical person to transfer ownership of a building or title deed where this is in the public interest in return for appropriate and prior compensation. Article 128: The withdrawal of customary rights where required by the public interest Where the public interest requires the withdrawal of customary rights to a parcel of land, a process of declaring and evaluation of these rights, followed by compensation or equivalent, is used for the evacuation process. However, without a clear definition of ‘public interest’, multiple interpretations may arise in practice. The law should list more clearly the areas that may qualify as ‘public interest’ to increase transparency and ensure a fair process. The FAO Guidelines support both state and non-state actors to work in a transparent way by ‘widely publicizing processes’ (Section 17.5) and ensuring clarity. The articles outlining the consultation process (which occurs prior to any compulsory purchases) should be further developed. The draft code in Article 105 refers to the need to conduct a consultation process before any expulsion or expropriation can occur. Article 105: Public consultation All compulsory purchases must be preceded by a public consultation period with a minimal duration of one month and a maximum of four months, which must be widely communicated in order to allow all interested parties particularly those affected by the compulsory purchase, to assert their rights. This section of the code would benefit from being developed with clear guidelines outlining this process. This is to ensure that these consultations are held in a fair, transparent and participatory manner, and will prevent any chance of misinterpretation when implemented. The article forbidding any construction, planting or improvements on land during the expropriation process will put the owner of the land at a significant disadvantage. Concerns were raised about Article 107, which states that once a declaration has been made that a piece of land is required for ‘public interest’ then the owner cannot undertake any construction on the land, and no planting or improvements can be carried out during the expropriation procedure. 15 Article 107: Ban on construction and planting after the publication of the decree announcing the public interest Following the decree announcing the public interest, no structure may be erected, no planting may take place and no improvements may take place on the land subject to the aforementioned project. This article therefore puts the owner of the land at a significant disadvantage while they wait for the expropriation procedure. For example, if the land belongs to a farmer who depends on the land for their livelihood, including food security, then they will be at an enormous risk if they are forbidden to plant. This is especially true if there is a long appeal process or there is a delay in obtaining compensation. The expropriation process should therefore be amended to take this into account. The expropriation process must not be drawn out and costs of appeal should be covered by the state. The state must ensure it has sufficient funds to effectively implement this law (including the expropriation costs) effectively. Article 108 lays out the process if the administration and the person subject to the compulsory purchase are unable to agree the amount of compensation after a maximum period of six months. It states that each side should assign two experts to write a report and submit it to the court who will make a final decision. Article 108: Determining compensation for compulsory purchases The compensation for compulsory purchases must be fixed by mutual agreement. If an agreement is not reached within a maximum of six (6) months, the complainant may bring the matter before the relevant competent court. Two experts must be assigned by the administration and two by those subject to the compulsory purchase. These experts must submit their report to the relevant competent court within a maximum of one month after their appointment. Though the intention to have a third party review the compensation claims is welcome, there is concern over whether the person being expropriated will have to cover these costs. It is argued that because it is the administration who initiates the expropriation, it is fair that the administration covers these appeal costs. Sections 6.6, 9.10 and 10.3 of the FAO Guidelines place particular emphasis on providing legal assistance and minimised costs. Section 6.6 places emphasis on the ‘vulnerable and marginalized groups’, while section 10.3, the ‘farmers and small-scale food producers’. The issue of whether the state has sufficient funding to effectively implement the draft land code, including procedures such as the above, is a significant concern. It is important that these processes are not too long and drawn out, given the urgency of the situation for the person facing expropriation. 16 Loss of future earnings should be taken into consideration as part of compensation. Article 109 lays out the conditions for agreeing the amount to give in compensation, including value of the property, and any capital gains or losses resulting from the compulsory purchase not taking place. Article 109: Establishing compulsory purchase compensation Compulsory purchase compensation shall be established in consideration of the following in all cases: The state and current value of the property as of the date of the compulsory purchase ruling or the judicial decision authorising the amicable transfer of ownership; The resulting capital gain or capital loss of the property not being purchased as part of the execution of the planned project; The full payment of all excise and duties related to the property in question. Each of the elements given in the above section will be used to calculate the overall sum. The compulsory purchase compensation must only cover actual and proven damages directly caused by the compulsory purchase. It should not cover unproven, potential or indirect damages. However, loss of future earnings has not been accounted for in assessing compensation. This should be considered as part of the compensation amount and must be based on clearly defined criteria – for example, future income lost during the transition period to utilising a new piece of land. A longer notice period (than one month) should be given once the compensation ruling is finalised. Article 112 clarifies that once the compensation process ruling is finalised, payment by the administration must be made, and one month later it can take possession of the building. Article 112: Payment of compensation and taking possession of the building Following the ruling of the President of the Court, the appellate jurisdiction is stopped following the case, and the administration will pay all compensation or, in the event of repairs to be made to the compulsory purchase property to be received, these must be submitted to the Clerk of the Court. The administration may take immediate possession of the building one month after the conclusion of this process. Concerns were raised about this relatively low notice period to evacuate a building. Participants in N’Djamena especially, highlighted the difficulties in finding and moving to proper housing and raised concerns about high housing costs. It was suggested that six months would be a more appropriate notice period. Section 16.9 of the FAO Guidelines warns that ‘Evictions and relocations should not result in individuals being rendered homeless’ and that ‘where those affected are unable to provide for themselves, States should, to the extent that resources permit, take appropriate measures to provide adequate alternative housing’. 17 Missing aspects The code should contain articles specific to rural land and articles specific to urban land. It was suggested by participants that, rather than combine urban and rural land issues together in one code, it would be beneficial to have a section of the land code devoted to rural land and a section to urban land. It was felt that doing so would help to address issues applicable to rural land and issues applicable to urban land; therefore, the code could be tailored to their different requirements. Having one land code that is supposed to be applicable to both rural and urban land may put some communities at a disadvantage. For example, effective mediation over land disputes may differ significantly in a rural and an urban setting. A provision should be included that allows for mediation as a mechanism for resolving land-related disputes. Following on from this, one aspect that participants considered to be missing from the land code is a provision for settling land disputes using mediation techniques at a local level. One of the most common methods of conflict resolution in rural areas is done through local-level leaders such as village chiefs or elders. If an amicable solution cannot be found, an official conflict resolution procedure may be undertaken at a departmental level. If the matter is not settled at this level, then the complainant may appeal to the higher courts. However, as mentioned previously, these facilities are few and far between and rarely accessible to communities at a local level. Local-level mediation, done effectively, has the potential to mitigate the need for higher level courts. Though the land code makes provision for mediation in the expropriation and eviction processes, the code could go further and make a provision for establishing mediation groups. These groups could work with local leaders to undertake conflict prevention work, for example, by working with groups or individuals going through expropriation and eviction processes, to settle conflicts before they develop. In addition, they could act as a mediator in cases of escalating conflict, or support the local leadership as it strives to do so. Support for local mediation efforts for land disputes is found in Sections 9.11, 25.3 and 21.3 of the FAO Guidelines, the latter of which confirms ‘States should strengthen and develop alternative forms of dispute resolution, especially at a local level. Where customary or other established forms of dispute settlement exist, they should provide for fair, reliable, accessible and non-discriminatory ways or promptly resolving disputes.’ 18 Potential loophole Clarification is required for the conditions by which the Council of Ministers can allocate land over 10 hectares. One area identified as a potential loophole which could potentially have a negative impact on communities is with the allocation of plots, especially in rural areas. Article 44 lists the maximum number of plots that each level of authority can allocate to a single stakeholder. Article 44: Competent authorities for the provisional allocation of provisional or permanent rural concessions and their revocation Provisional rural concessions are allocated: by order of the local Prefect up to two (2) hectares; by order of the Governor up to five (5) hectares; by order of the Ministry of Land Affairs up to ten (10) hectares; by decree of the Council of Minsters over ten (10) hectares. The definitive grant or revocation shall be established by the authorities above within the scope of their competencies and the conditions set out in the present law. However, it is not clear what the conditions are for their allocation. There is concern that a lack of clarification could lead to abuse or misinterpretation of the law by the authorities. It is especially important that clarification be given for the conditions by which the Council of Ministers can allocate land over 10 hectares. This is key to supporting the transparency of the way land is allocated. Sections 12.5 and 12.6 of the FAO Guidelines affirm the importance of transparency, with section 12.5 stating that ‘States should with appropriate consultation and participation, provide transparent rules on the scale, scope and nature of allowable transactions in tenure rights and should define what constitutes large-scale transactions in tenure rights’. 19 Conclusion This draft code has the potential to benefit the 80% of Chadians (USAID 2010) who depend on land for their livelihood, though improvements and amendments are required, as outlined above. The draft code goes some way towards aligning itself with the principles of the FAO Guidelines, however alignment could be strengthened in a number of areas, including eviction and expropriation processes and local level mediation. It is important that due care is taken for the law to be implemented effectively and the following issues must be carefully considered. Community participation is absolutely essential for the development and implementation of this code, and further research should be undertaken to help strengthen it. It is unclear what level of community participation occurred in the formation of this draft code, though stakeholder interviews suggest this was limited. Therefore, it is essential that, given the large percentage of the population dependent on land for their livelihood, further consultations are held at a community level in order to strengthen the recommendations for this code. It will be particularly important to consult with women’s groups, as, though the draft code itself does not discriminate based on gender, there may be challenges implementing this principle at a local level. Customary and traditional authorities must also be included in all land-related discussions. This study therefore recommends that further research be undertaken to enable a wider participation of stakeholders, ensuring greater diversity of input into the formation and implementation of this proposed new land code. Communities must be made aware of their rights under the code – both remaining and new. Local officials must be trained to help implement them. It is important to recognise that the majority of the Chadian population (63%) are illiterate (World Bank 2012). Therefore, while the FAO Guidelines are correct when they state in section 6.4 that ‘Explanatory materials should be widely publicized in applicable languages and inform users of their rights and responsibilities’, for this law to be implemented effectively it is essential that additional tools are used to ensure the population of Chad are made aware of this new land code. It will take time for the population to adapt to the new code and therefore will be necessary to allow time for awareness raising. This process therefore could be started prior to its adoption. 20 It will be of paramount importance that rural farmers are made aware of their rights under the proposed new law – both rights that are remaining and new rights. It is also important that local and regional government officials are trained in how to implement this law and that effective structures are put in place to support its implementation. A rural land service should be established at the sub-prefecture level. In order to address these challenges and aid the implementation of the land code in rural areas, a rural land service should be established at the sub-prefecture level with the purpose of specifically addressing the land needs of rural communities. This rural land service could have the following role: Establish land management committees, and train them to enforce the law. Train local officials and civil society groups, and sensitise communities to be familiar with the law. Ensure the management and security of common land and natural resources for common use, and land used for sacred sites and rituals for worship. Work in collaboration with the village land commissions to ensure the rural land records are kept up to date at a local level. This recommendation is supported in section 6.4 of the FAO Guidelines, which states that services should be delivered to all, ‘including those in remote locations’, and section 11.5, which requests that states ‘establish appropriate and reliable recording systems, such as land registries’. Sufficient funding must be in place for all areas required to implement this code effectively. Questions remain about whether sufficient funding has been allocated to the implementation of the proposed new land law once it is passed. The international community will have a significant role to play in supporting the government of Chad in this process. 21 Recommendations Based on this research on the draft land code, the following recommendations are presented: 1. For clarification: The term ‘customary rights’ must be clearly defined. The definition of ‘permanent and evident’ ground coverage must be clearly defined. The term ‘public interest’ should be clearly defined. Clarification is required for the conditions by which the Council of Ministers can allocate land over 10 hectares. 2. For amending: The process for obtaining land titles should be simplified and the costs significantly reduced. The article forbidding any construction, planting or improvements on land during the expropriation process will put the owner of the land at a significant disadvantage and should be revised. Loss of future earnings should be taken into consideration as part of compensation. A longer notice period (than one month) should be given once the compensation ruling is finalised. 3. For further consideration: The articles outlining the consultation process (which occurs prior to any compulsory purchases) should be further developed. The expropriation process must not be drawn out and costs of appeal should be covered by the state. The state must ensure it has sufficient funds to effectively implement this law (including the expropriation costs) effectively. 4. For provisions to be added: The code should contain articles specific to rural land and articles specific to urban land. A provision should be included that supports mediation as a mechanism for resolving land-related disputes. 5. For implementation: Community participation is absolutely essential for the development and implementation of this code and further research should be undertaken to help strengthen it. Communities must be made aware of their rights under the code – both remaining and new. Local officials must be trained to help implement them. A rural land service should be established at the sub-prefecture level. Sufficient funding must be in place for all areas required to implement this code effectively. 22 Bibliography All websites accessed January 2015 EEMET (2014) ‘Rapport de Consultance sur le Project de Loi Fonciere et Domaniale au TChad’ (unpublished) Food and Agriculture of the United Nations (FAO Guidelines) ‘Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security’ www.fao.org/docrep/016/i2801e/i2801e.pdf Gouvernement du Tchad (2013) ‘Projet de loi portant code foncier et domanial du Tchad’ (unpublished) La Loi n°23 du 22 juillet 1967 portant statut des biens domaniaux La Loi n°24 du 22 juillet 1967 relative à la propriété foncière et aux droits coutumiers La Loi n°25 du 22 juillet 1967 portant limitation aux droits fonciers Maps courtesy of Google Maps United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2014) Human Development Reports http://hdr.undp.org/en/data USAID (2010) USAID Country Profile, Property Rights and Resource Governance: Chad http://usaidlandtenure.net/sites/default/files/country-profiles/fullreports/USAID_Land_Tenure_Chad_Profile.pdf World Bank (2012) Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS World Bank (2013) Country Data: Chad http://data.worldbank.org/country/chad World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) World Health Statistics 2014 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112738/1/9789240692671_eng.pdf?ua=1 23 24