A Program to Compute Approximate Confidence ANOVA-based Mean Squares

advertisement

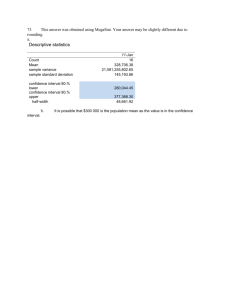

A Program to Compute Approximate Confidence Intervals on Certain Linear Combinations of ANOVA-based Mean Squares Brandon L. Paris Page 1 of 8 Overview of Program This program was written to allow simple calculation of approximate confidence intervals for linear combinations of ANOVA-based mean squares estimates. The linear combinations must follow one of the following forms: Q θ = ∑ c MS i i , or (1) i =1 Q P θ = ∑ ci MS i − i =1 ∑ c MS j j , (2) j = P +1 where all ci (i = 1, 2, . . . Q) are positive and the MSi are the ANOVA-based mean squares estimates. The methods used in the program are from the text Confidence Intervals on Variance Components by Burdick and Graybill and are based on large-sample approximations. The user is directed to this source for further information. The software makes use of several routines from DCDFLIB to obtain the F and χ2 quantiles necessary to compute the confidence intervals. The library, written by Brown, Levato, and Russell, provides routines that will make various computations for a number of statistical distributions and is available in both C and Fortran on the World Wide Web at http://odin.mdacc.tmc.edu or http://www.netlib.no. Using the Program Once linked and compiled, the program is invoked through the command-line as follows: > interval Invoking the program in this manner will print output only to the display console. To also print the results to an output file, use the call: > interval outfile where outfile is the name of the file the results will be placed. The program will prompt the user for several inputs. Q The total number of sources of variation (SOV) in the linear combination. P The number of SOV to be included in the first summation. When Q = P, the linear combination is like (1), otherwise, the linear combination is like (2). type The type of confidence interval: one-sided upper CI, one-sided lower CI, or two-sided confidence interval α (alpha) Proportion in (0,1) where the confidence level for the interval is (1–α) for one-sided intervals or (1-2α) for two-sided intervals. ci Constant to be multiplied times the ith mean square included in the linear combination. MSi The ith mean square included in the linear combination. dfi The degrees of freedom associated with the ith mean square included in the linear combination. Page 2 of 8 At times, the software may produce negative estimates of the lower and/or upper confidence limits. The software handles this differently depending on which form θ takes. If θ is of form (1), then it is constrained to be non-negative, and hence the confidence limits will follow this same constraint. If, however, θ is of form (2), then there are no general sign constraints on θ and the user must assess whether the final results make sense. For instance, a user may calculate a linear combination of form (2) in an attempt to estimate a variance, which must be non-negative. In this situation, negative confidence limits should be interpreted as zero by the user. At other times, the goal may be to determine whether two variances are statistically different. In this instance, negative confidence limits will probably be acceptable. Examples Example One (Small Sample Sizes) Lorenzen and Anderson (1993) provide data for an experiment measuring the firing time of explosive switches where there were three factors of interest: the metal used in the switch, amount of primary initiator, and the packing pressure of the explosive. A completely randomized design was used for the experiment. Because the metal used for the switches was made of recycled material, metal was considered to be a random effect while the remaining factors were considered to be fixed. The experiment showed that only the metal used and amount of primary initiator were effecting firing time. As a result, the final ANOVA for the experiment included only these sources of variation and their interaction. This final ANOVA table, including the expected mean squares, is provided in Table 1. As an example, consider that estimating the total variability of firing times is of interest. Simple manipulation of the EMS from Table 1 shows that 2 σ Total = 1 1 7 EMS1 + EMS 3 + EMS 4 , 18 6 9 which can be estimated by 2 σˆ Total ≈ 0.0556MS1 + 0.1667MS 3 + 0.7778MS 4 . 2 In this example, Q = P = 3. Using the software, σˆ Total = 263.27 and the 95% two-sided confidence interval for 2 σ Total is (111.8, 1.78x105). A specific listing of both the inputs and program output is provided in Figure 1. Table 1. Final ANOVA for Experiment of Explosive Switches from Lorenzen and Anderson (1993). Source Metal df 1 SS 3136.00 MS 3136.00 Initiator 2 513.72 256.86 EMS 2 = σ 2 + 6σ Metal *Initiator + 12Φ ( I ) Metal*Initiator 2 969.50 484.75 2 EMS 3 = σ 2 + 6σ Metal *Initiator 30 35 318.00 4937.22 10.60 Error Total EMS 2 EMS1 = σ + 18σ Metal 2 EMS4 = σ 2 Page 3 of 8 Table 2. ANOVA for Nested Experiment presented in Box, Hunter, and Hunter (1978). Source df SS MS EMS Batches 14 1,211.0 86.6 2 σ Tests 2 + 2σ Samples Samples(Batches) 15 869.7 58.0 2 2 σ Tests + 2σ Samples Tests(Samples Batches) Corrected Total 30 59 27.5 2,108.2 0.9 2 + 4σ Batches 2 σ Tests This example is presented to show the limitations of the software for use with data with small sample sizes (small degrees of freedom for metals, initiators, and their interaction), and the fairly wide confidence intervals should convince the reader that limitations do exist. Thus, the user should proceed with caution when interpreting the results in these situations, as the calculated interval could be too wide to be of any use. Example Two (Large Sample Sizes) Box, Hunter, and Hunter (1978) present data obtained from a batch process for manufacturing a pigment paste where the moisture content of the product is of interest. A nested experiment was conducted, where 15 batches of pigment paste were sampled 2 times each, and each sample was tested for moisture content twice. Table 2 shows the ANOVA for this study corrected for the mean. A goal of the study was to understand the variability in moisture content attributable to differences in batches as well as the variability caused by sampling technique. Based on the expected mean squares, the variance components for Batches and Samples(Batches) can be estimated by 2 σˆ Batches = 2 σˆ Samples = MS Batches − MS Samples 4 MS Samples − MS Tests 2 , and , 2 2 respectively. The program computed the 95% two-sided confidence interval for σ Batches and σ Samples as (-15.0, 39.7) and (15.4, 69.0), respectively. Note that the user would interpret the first interval as (0, 39.7) in order to satisfy the constraint of non-negative variances. Figures 2a and 2b show the program output for these confidence intervals. Page 4 of 8 Figure 1. Listing of Inputs and Results for Example 1. Confidence Intervals on Linear Combinations of Expected Mean Squares Enter Q . . . 3 Enter P . . . 3 1) One-Sided Lower Confidence Interval (Upper Bound), 2) One-Sided Upper Confidence Interval (Lower Bound), or 3) Two-Sided Confidence Interval Type of Confidence Interval to compute . . . 3 Enter alpha such that (1-2*alpha)*100% is the confidence level 0.025 Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter c[1] MS[1] df[1] c[2] MS[2] df[2] c[3] MS[3] df[3] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.05556 3136 1 0.16667 484.75 2 0.7778 10.60 30 Confidence Intervals on Linear Combinations of Expected Mean Squares Q = 3 P = 3 Interval Type: i --1 2 3 c[i] ------0.056 0.167 0.778 Point Estimate: Two-sided CI MS[i] ------3136.0 484.8 10.6 df[i] ------1.0 2.0 30.0 theta_HAT = 263.274 95.0% Confidence Interval (111.773, 177533.738) Page 5 of 8 Figure 2a. Listing of Inputs and Results for Example 2 (Batches Source of Variation). Confidence Intervals on Linear Combinations of Expected Mean Squares Enter Q . . . 2 Enter P . . . 1 1) One-Sided Lower Confidence Interval (Upper Bound), 2) One-Sided Upper Confidence Interval (Lower Bound), or 3) Two-Sided Confidence Interval Type of Confidence Interval to compute . . . 3 Enter alpha such that (1-2*alpha)*100% is the confidence level 0.025 Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter c[1] MS[1] df[1] c[2] MS[2] df[2] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.25 86.6 14 0.25 58.0 15 Confidence Intervals on Linear Combinations of Expected Mean Squares Q = 2 P = 1 Interval Type: i --1 2 c[i] ------0.250 0.250 Point Estimate: Two-sided CI MS[i] ------86.6 58.0 df[i] ------14.0 15.0 theta_HAT = 7.150 95.0% Confidence Interval (-15.029, 39.678) Page 6 of 8 Figure 2b. Listing of Inputs and Results for Example 2 (Samples within a batch Source of Variation). Confidence Intervals on Linear Combinations of Expected Mean Squares Enter Q . . . 2 Enter P . . . 1 1) One-Sided Lower Confidence Interval (Upper Bound), 2) One-Sided Upper Confidence Interval (Lower Bound), or 3) Two-Sided Confidence Interval Type of Confidence Interval to compute . . . 3 Enter alpha such that (1-2*alpha)*100% is the confidence level 0.025 Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter Enter c[1] MS[1] df[1] c[2] MS[2] df[2] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0.50 58 15 0.5 0.9 30 Confidence Intervals on Linear Combinations of Expected Mean Squares Q = 2 P = 1 Interval Type: i --1 2 c[i] ------0.500 0.500 Point Estimate: Two-sided CI MS[i] ------58.0 0.9 df[i] ------15.0 30.0 theta_HAT = 28.550 95.0% Confidence Interval (15.372, 69.006) Page 7 of 8 References Brown, Barry W., James Lovato, and Kathy Russell. DCDFLIB: Library of C Routines for Cumulative Distribution Functions, Inverses, and Other Parameters. Houston, TX: The University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1994. Burdick, Richard K. and Franklin A. Graybill. Confidence Intervals on Variance Components. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1992. Lorenzen, Thomas J. and Virgil L. Anderson. Design of Experiments: A No-Name Approach. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1993. Box, George E. P., William G. Hunter, and J. Stuart Hunter. Statistics for Experimenters: An Introduction to Design, Data Analysis, and Model Building. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1978. Page 8 of 8