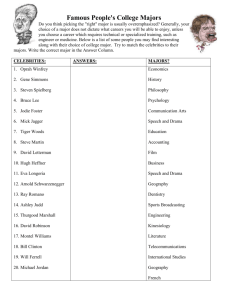

Discriminating Among Educational Majors and Career Aspirations

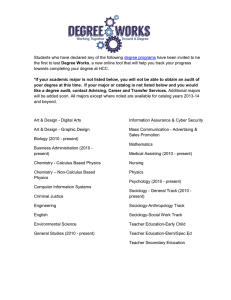

advertisement