T C I S

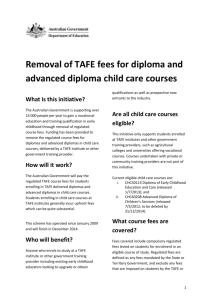

advertisement